The following is an excerpt from my forthcoming Greek grammar textbook. I am sharing it now because of its relevance to my review of “Basics of Verbal Aspect in Biblical Greek” by Constantine Campbell.

Functional Morphemes Related to Verbs

When we introduced functional morphemes, we said that they help to situate the things that lexemes refer to in the world. Determiners do so by specifying how the entities in the world relate to the knowledge of the speaker and addressee. Tense and aspect situate eventualities temporally in the world. Modality and mood situate eventualities in the real world or in hypothetical worlds.

There is probably no topic that has caused a greater amount of confusion for both scholars and students than tense and aspect. While lack of space precludes a full discussion of all the views within NT scholarship on these semantic categories, it must be clearly said at the outset that tense and aspect are both temporal categories. More specifically, aspect is not spatial, and labelling it “perspectival” is also very misleading. There is no debate about this within linguistics, and I would refer any to the preface for a brief discussion of the problems with this view and its relationship to the wider world of linguistics. The second important thing for the student to remember is that Greek is not particularly special when it comes to aspect. Although tense is often viewed as a basic, easy-to-understand concept, aspect is often viewed as an ethereal category that Greek expresses in a special way. Statements like the following from Mathewson and Ballantine Emig (2016:113) are commonplace:

Though there is still some disagreement on the issue of whether Greek indicative verb tenses indicate time, our grammar will side with advocates of verbal aspect in the treatment of the Greek tense system. But one must at least agree with Robertson (824-25) that time is but a subordinate element in Greek verb tenses.

By way of contrast, the English tense system primarily indicates time (past, present, future). However, in a more limited way even English can indicate aspect. What is the difference between these two statements?

I studied Greek last night.

I was studying Greek last night.

Both refer to the same event, the act of studying Greek, and the same time, last night. The difference is one of aspect, how the speaker chooses to portray the action: as a simple whole (“studied”) or as in progress (“was studying”).

The suggestion by Mathewson and Ballantine Emig is that English expresses aspect “in a more limited way,” but the Greek verbal system, on the other hand, “primarily” indicates aspect. This, however, is a failure to recognize the complexity of English’s system, and at a deeper level, it reflects a misunderstanding of what aspect is. In fact, I know of no other language that can make as many aspectual distinctions as English. Not only can we say I studied Greek last night, but we can say I had studied Greek last night as well as I had been studying Greek last night (all of which are past tense and are distinguished based on aspect), and we can even make the same aspectual distinction in the future (which is much rarer in the world’s languages) with I will have been studying Greek tomorrow night. In contrast, the Greek system would allow for a similar three-way contrast between I studied/was studying/had studied, but it would not readily allow for I had been studying, and that three-way distinction is only found in the past tense in Greek. English has a four-way contrast in the past, present, and future. Suffice it to say, English’s aspectual system is tremendously complex. Although Greek has its own nuances and idiosyncrasies (like any other language), it is not particularly unique in the amount of aspects encoded in the verbal system.

With these caveats in mind, I present here the standard analyses of tense, aspect, and aktionsart in linguistics and apply them briefly to the verbal forms in NT Greek. This section is designed to help you understand the linguistic categories better. If you are interested in the full range of meaning of the forms and all their uses, I suggest going through each use of the forms in light of the definitions and categories developed here.

At the outset, we must note that the notional categories we introduce may map onto a particular language’s verbal forms only partially. For example, we might define the notional category of present tense as an overlap between the time when the utterance is made and when the eventuality takes place. This would require that each time the present tense is used in spoken or written text, the eventuality would hold at the time concurrent with the speaker. If we defined the present tense in this way, it does not tell us whether the Greek morpheme that we normally associate with present tense (the Luo or present form) refers to the same notional category. It may refer to a concept that is similar but not identical to the way we have defined the present tense. This is what I mean when I say that the notional category we introduce may only partially map onto Greek’s verbal forms. Given that the notional categories in linguistics have been developed based on the how the languages of the world operate, it is probably the case that some category has already been developed that fits the morphemes in Greek, but we may have to tweak our notional category in order to make it fit the data we find in NT Greek.

Tense

The term tense is used in a variety of ways. It is sometimes used to refer to a verb form, such as in the phrases present/imperfect/future tense forms. I do not use the term like this, and whenever I want to refer to a form, I will either use the term “verb form” or will refer to the form itself by its morphological shape, such as Luo (present), Eluon (imperfect), Luso (future), Leluka (perfect), or Aorist (since there are two “shapes” for this category, namely Elusa and Efagon; see for justification of this naming practice). In semantics, the term “tense” refers to the location of an eventuality in time. Because tense is how the speaker situates the eventuality in time, the prototypical case is when the time of the eventuality is related to the time of speaking. For example, if I say Laura ate pizza and watched “The Lord of the Rings” last night, the typical way to understand this is that the eventualities of Laura eating pizza and watching the greatest movie of all time occurred prior to when I initially made the utterance. In fact, we can be more specific about the time of these events—they did not just occur prior to when the utterance was made, but they happened at a specific time prior to the utterance, in this case specified by last night. Even if we were to take this adverbial phrase out however, we would still understand that the events of Laura eating pizza and watching LOTR happened at a specific time in the past. Context would usually make clear when exactly this event occurred. Thus, when we use a past tense verb form (like ate or watched), we are making a claim about what occurred at a particular time.

In discussing our sample sentence, we introduced distinct time periods or intervals. First, there was a time of speaking, or the time when the utterance was made. We will call this the Temporal Anchor (TA) because it provides the anchor to which other times are related. It is often, but not always, the time of speaking. Second, we said that there was a time when the eventuality took place. This we will call the Event(uality) Time (ET). It is when the eventuality took place (or will take place) in the real world. The astute reader will have also noticed that we discussed a third time interval. This is the time in which we are making a claim about the world, which we will call the Reference Time (RT). Tense, aspect, and aktionsart are all concerned with relationships between or properties of these three time intervals.

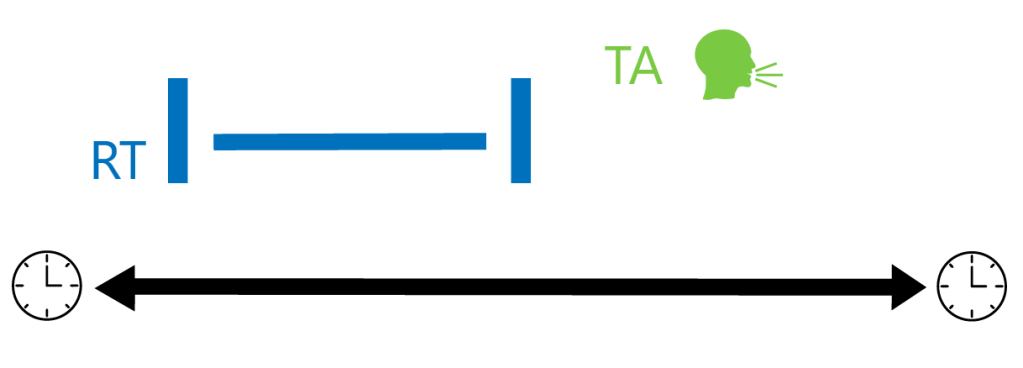

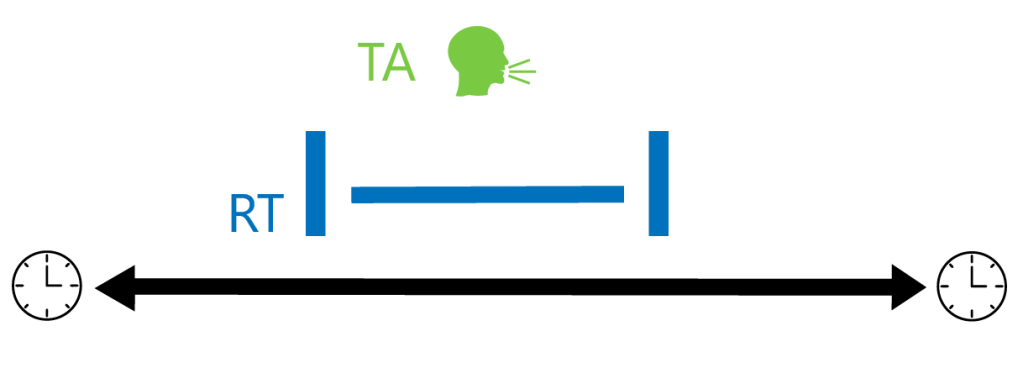

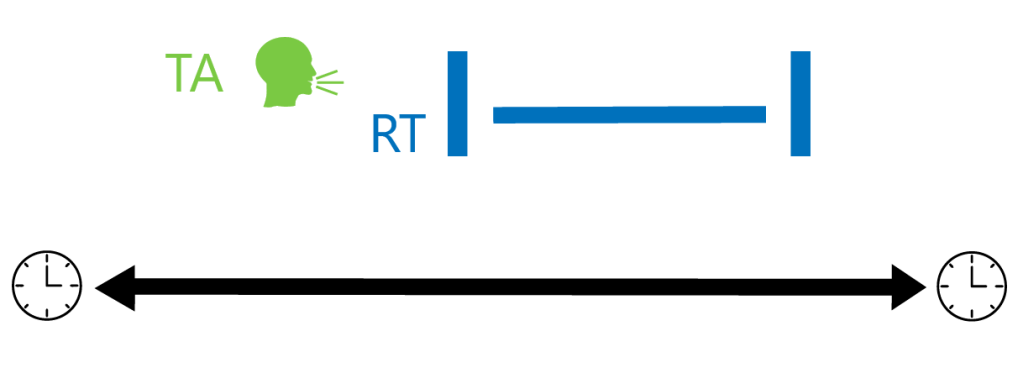

In our description of the past tense, we said that the speaker makes a claim about the world at a certain time. Given this description, we can see that tense is not a relationship between the TA and when the event takes place (the ET), but it is a relationship between the TA and when the claim is made about the world (the RT). This is what tense does—it specifies the relationship between the speaker’s TA (often the speech time) and the RT, the time the speaker is referring to. More concretely, past tense says that the speaker is making a claim about a time prior to the TA, present tense says that the speaker is making a claim about a time that is concurrent with the TA, and future tense says that the speaker is making a claim about a time that follows the TA. These are all temporal relationships that can be depicted using temporal intervals/points.

Figure 1: Past Tense Meaning

Figure 2: Present Tense Meaning

Figure 3: Future Tense Meaning

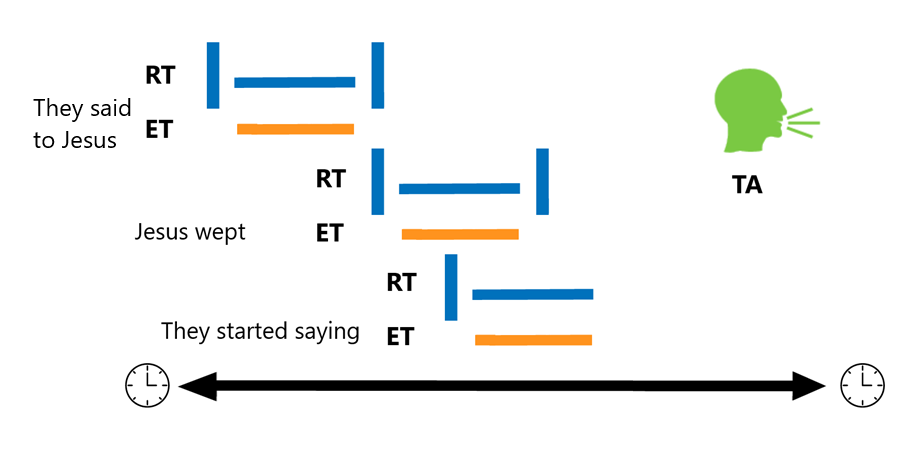

The specific claim that is being made about the RT is that the ET is related to that time in some way (usually by being at least partially included in it). For example, in the simple sentence ἐδάκρυσεν ὁ Ἰησοῦς ‘Jesus wept’ (Jn 11:35), John is making a claim about a specific time in the story, namely after Jesus is told to come and see Lazarus. This is when the event of Jesus weeping takes place, as depicted in the following diagram:

Figure 4: Narrative Progression Temporal Diagram

The purpose of this diagram is to show how the three time intervals/points of the TA, RT, and ET are related to one another within a text. Each of the events described in John 11:34-36, occurs in the past, i.e. they occur prior to the TA, the speaker’s time of writing. Hence, all of the RTs are depicted to the left of the TA. As the narrative progresses, a new claim is being made about a new time. This is the hallmark of narrative—temporal progression. The first event occurs prior to Jesus weeping when people tell Jesus to come and see where they laid Lazarus. This event, represented by the ET, happens at a specific time in the past, as indicated by the initial RT. The event of Jesus weeping occurs after the time when people initially speak to Jesus, so a new RT (given in the middle) begins with this event. The final RT overlaps with the time when others start to say something else. In each case, a claim is being made about a specific RT. That is what tense is—it relates the TA to the RT, the time to which the ET is related (on which, more below).

With the description of tense we have given, we can provide a basic analysis of even some of the more difficult uses of the various tenses in Greek. The Luo form, which encodes present tense, is by far the most problematic. It is not, however, particularly special when it comes to present tenses, which are notorious for being used to refer to all kinds of times besides the speaker’s current speech time (see Klein 2009 for many examples of this in English). We have already said that this definition of tense is too narrow and cannot account for the data—the TA is not limited to the time when the utterance is made. As soon as we recognize this however, we can account for so-called counterexamples to the Luo form being a present tense. The historical present is a classic example and is found in many languages with a present tense (including English):

- ἔρχεται Ἰησοῦς καὶ λαμβάνει τὸν ἄρτον καὶ δίδωσιν αὐτοῖς

‘Jesus comes and takes the bread and gives (it) to them.’ (Jn 21:13)

If the TA can shift to the time of the story itself when a story is being told, the Luo verbs ἔρχεται, λαμβάνει, and δίδωσιν are all still true presents in this example. The TA itself is set in the past at the time of the story, so the time of the claim (the RT) overlaps with the TA, which is how we have depicted present tense in . As is commonly supposed, this is probably done by the speaker in order to present the story to the hearer as actively unfolding. Given that this is a phenomenon found in a variety of languages and that it is the standard analysis in the semantics literature, we need not belabor this point.

In other cases, the present tense is used, but a shifting TA does not seem to be the best explanation. This is particularly true of examples where the event referred to by the verb is in the future, even though the present tense is used. These have been called “futurates” (Copley 2009:###), and an example is found in Luke 19:8:

- ἰδοὺ τὰ ἡμίσιά μου τῶν ὑπαρχόντων, κύριε, τοῖς πτωχοῖς δίδωμι

‘Behold, half of my possessions, lord, I am giving to the poor.’

In this example, Zacchaeus is not in the midst of giving anything to the poor. He is in the midst of talking to Jesus. However, the present tense is used (and it can be used in English as well in the same scenario). The reason the present tense can be used is because Zacchaeus has already decided that he is giving half of his possessions to the poor. Because the decision is the first stage in the event, we can use the present tense for events that have already been decided or scheduled to occur in the future. In other words, we are not shifting the TA in examples like these (it is still the time of utterance), but we are shifting the RT and including the ET in that time, namely in the speaker’s present. The futurate use of the present portrays the event as already having begun because it has, in some sense, actually begun insofar as the decision to engage in a volitional action is itself part of the action.

It may be asked, what makes the kinds of analyses we have given for the historical present better than simply saying that the present tense is not a tense at all? There are two main reasons for this. First, these uses are found in many other languages with verbs that refer to present time. Given this, there is almost certainly something about the notional category of the present tense that allows humans from diverse cultures, times, and languages to use present tense forms in the same way. Second, both the historical present and futurates are only found in specific contexts. This suggests that there is some meaning component in these contexts that is allowing or triggering these uses. For the historical present, this is narrative progression. There is something about telling a story that allows for the TA to shift, and we have already suggested a plausible answer: the speaker may use the present tense to immerse the addressee in the time of the story itself to draw attention to certain parts of the story. For futurates, the eventuality is scheduled or decided. The relevant meaning component here is the volitionality of the subject. Because futurates refer to events that happen in the future but have already been scheduled or decided, they imply that a volitional subject (a subject who can make decisions) is involved in the event. This predicts that if a volitional agent is not involved or the event cannot be planned, this use is not possible. Indeed, Copley (2008:261) notes that while the sentence The Red Sox play the Yankees tomorrow is fine, the unplannable event referred to in #The Red Sox defeat the Yankees tomorrow is not acceptable. Examples from NT Greek conform to this pattern. For these two reasons, we conclude that the present tense in Greek is a true present tense—we simply must adjust our notional category of what the present tense is from the overly simplistic definition of the event happening at the same time the utterance is made.

For many in NT Greek grammatical studies, tense has fallen out of vogue. However, what has often been rejected is an overly simplistic definition of tense that no one in the field of linguistics would hold to in the first place, namely one that relates the time of speaking to the time of the eventuality (e.g. see Campbell 2024:28). Once we allow for a more nuanced definition of tense, the “problems” with the luo and aorist forms as real tenses disappear. Besides the historical present, we have explained several supposed counterexamples to the aorist being a true tense in other sections (##). Thus, we affirm that the Greek verb forms do indeed encode tense, rightly understood, in the indicative mood. Each of the form’s tense values can be seen in the following chart:

| Past | Present | Future |

| Aorist, Eluon (imperfect), Lelukein (pluperfect) | Luo (present), Leluka (perfect) | Luso (future) |

Table: Tense values of Greek verbs

Aspect

Aspect is often informally described as the way that the speaker views the eventuality. This “viewing” of the eventuality is not spatial or physical—it is not as if the speaker uses aspect to describe whether he or she physically witnessed the event or is a certain distance away from it. Rather, the language of viewing is used as a metaphor for temporality: the speaker’s “viewing” refers to which temporal part(s) of the eventuality are being referenced (again, see my review of Campbell’s Basics of Verbal Aspect at Biblingo.org/blog for a more detailed discussion).

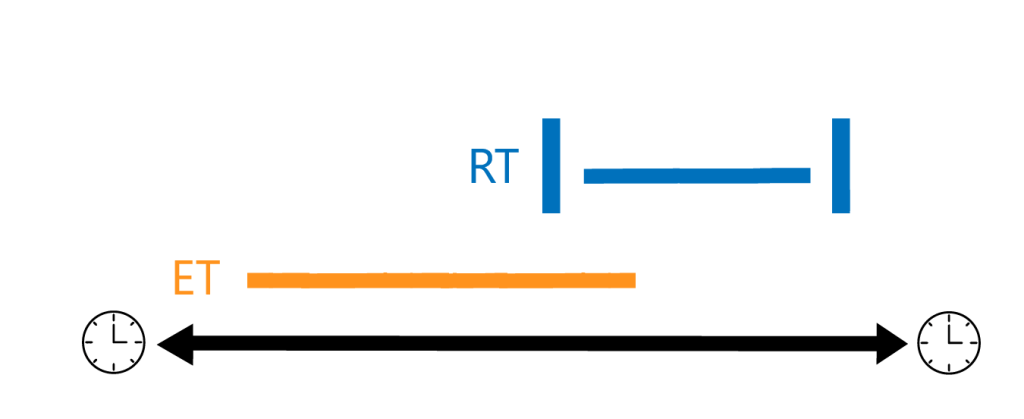

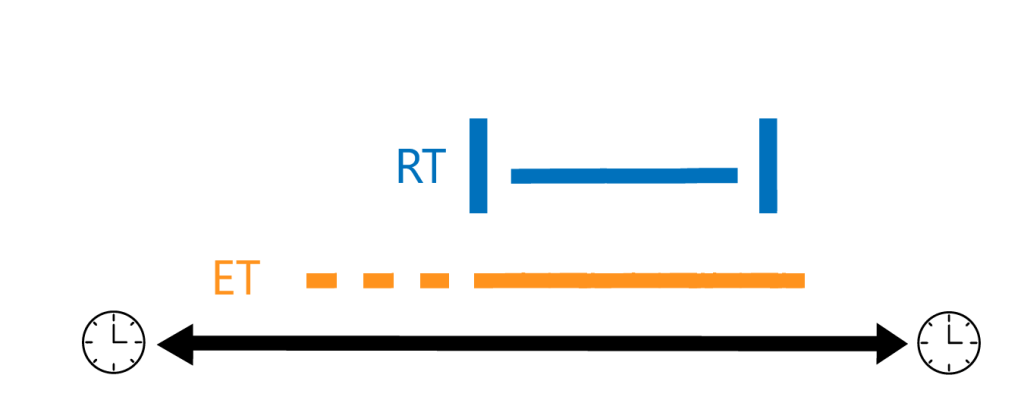

This sort of description implicitly makes reference to two time intervals, similarly to how tense made reference to two time intervals. First, there is the interval of the eventuality itself. We have called this the Eventuality Time, or ET. In an event of building a Lego house, there is a starting point, when the pieces are everywhere, and an endpoint, when the pieces have been assembled. Events and states of all kinds start and stop at various times, and the duration of the eventuality is a fact about the world and has nothing to do with how the speaker views it. The second interval is the time that the speaker is referring to, which we have called the Reference Time, or RT. If it takes me an entire afternoon to build a Lego house with my son, I may want to refer to only part of the time that we were building, so I may say We were building a Lego house when a meteor struck our car. In this example, I am referencing a time that does not include the end of the building-a-Lego-house event. We were in the midst of doing it when something else happened. The progressive form be + –ing is used in such an example to refer to part of the building-a-Lego-house event, a part that does not include the end of that event. In other words, only part of the ET is included in the RT. Hence, aspect is fundamentally a relationship between these two temporal intervals, one which the speaker chooses (the RT) and one which is a fact about the world (the ET).

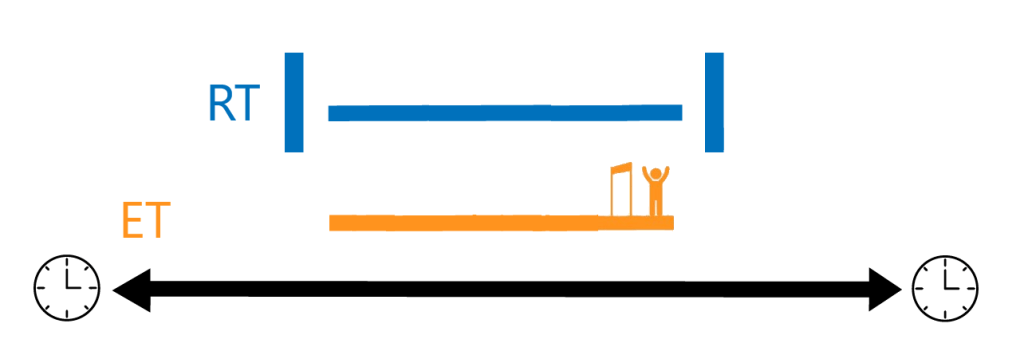

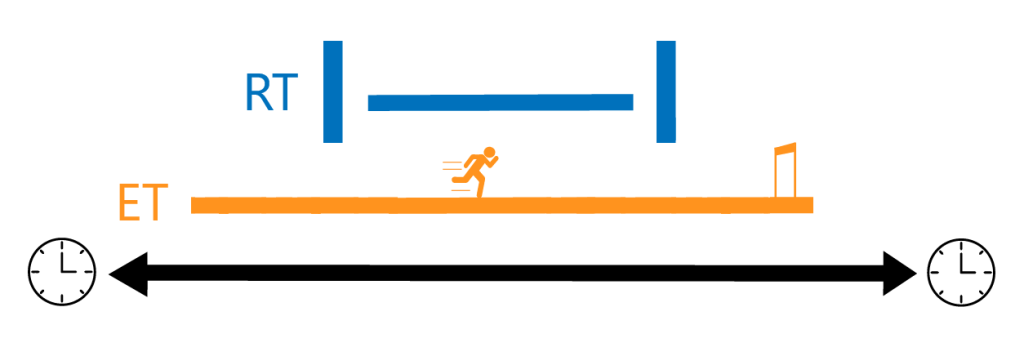

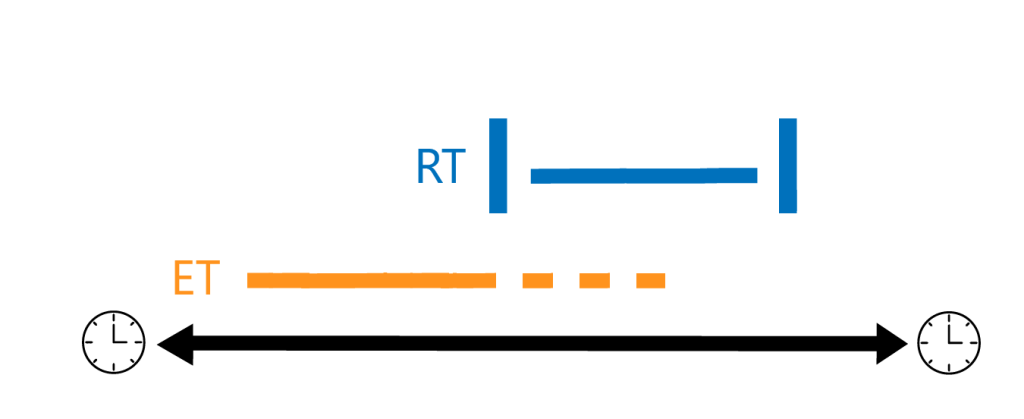

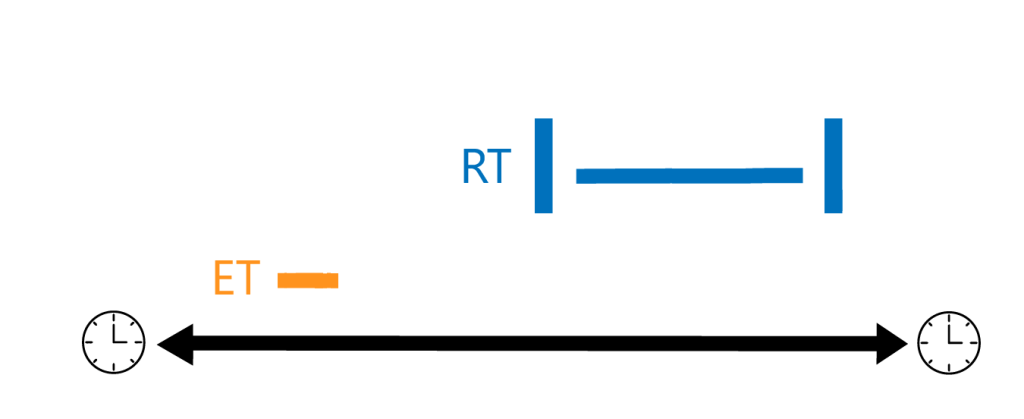

Utilizing this definition of aspect, we can provide simple definitions of the various aspects discussed in the literature. Just as the various tenses (past, present, and future) were the three possible relationships between the TA and the RT (RT before, during, and after TA), so the aspects are simply the logically possible relationships between the RT and the ET. At the outset, we note a complicating factor that we did not encounter with the tense relationships. The TA is ordinarily a point in time rather than an interval (the “moment of speaking” is normally a single moment), so it cannot extend beyond the RT. However, both eventualities and times that we talk about can be either points or intervals. Some eventualities, such as building a Lego house, last hours rather than a single moment in time, and we can just as easily refer to intervals of time (as in for 2 hours) as points of time (as in at 3 O’clock). Because the ET and RT can both be points or intervals, it is possible for either the ET to extend beyond the RT or the RT to extend beyond the ET. These time relations represent the basic distinction between imperfective and perfective aspect: imperfective is when the ET extends beyond the RT, and perfective is when the ET is included in the RT, as depicted in the diagrams.

Figure 5: Perfective aspect diagram

Figure 6: Imperfective aspect diagram

These diagrams depict particular interpretations of an eventuality. The ET is above the timeline and is depicted as being a time interval that represents the duration of a race. When we want to include the end of the race in the time interval we are talking about, we would say Nick ran the race. The normal interpretation of this sentence is that Nick finished running the race, so it is odd to say ?Nick ran the race but didn’t finish. When we want to exclude the end of the race in the time interval we are talking about, we would say Nick was running the race. The normal interpretation of this sentence is that Nick only ran part of the race, so it is not odd to say Nick was running the race, but didn’t finish (because he got tired). For events that have a natural endpoint (like running-a-race events), the perfective includes that endpoint, and the imperfective does not.

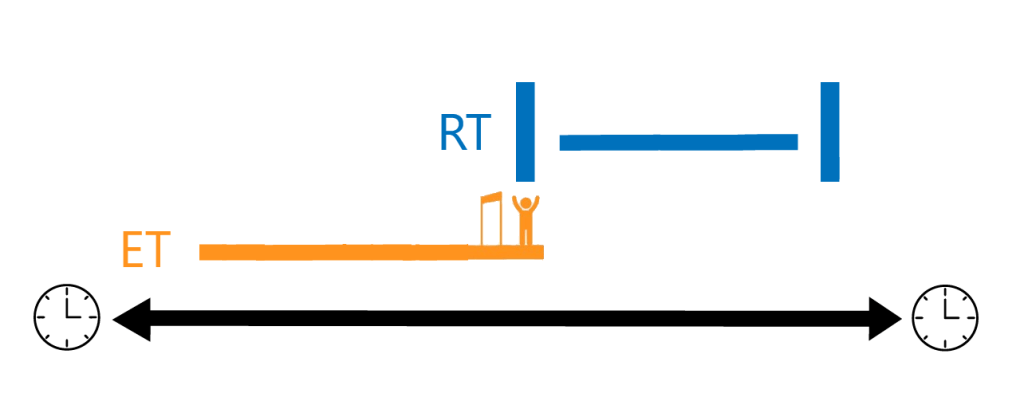

Another logical relationship would be when the ET precedes the RT. This is the basic definition of perfect aspect, as found in the sentence Nick has run the race. In this example at least, the end of the ET precedes the RT, so we can conclude (just like with perfective aspect) that Nick finished the race (again, it is odd to say ?Nick has run the race but didn’t finish). With the perfect, this means that we are talking about a time that follows the end of the time of the eventuality. We will nuance this below, but the following diagram depicts the basic temporal relationship of perfect aspect:

Figure 7: Perfect aspect diagram

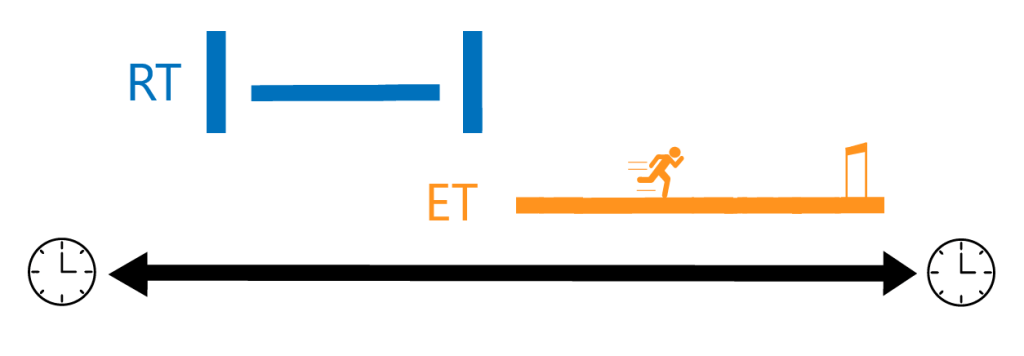

Of course, the final possible temporal relationship is where the ET would follow the RT. This has been called prospective aspect. In English, this meaning is conveyed with would as in a sentence like Nick said he would run the race. The time being discussed here is in the past (as indicated by the past tense would), but the time of Nick running the race comes after that time. This means that the ET follows the RT. Once again, we can depict this temporal relationship graphically:

Figure 8: Prospective aspect diagram

In Greek, there is no single morpheme that attaches to the verb that conveys this meaning (and English, also, uses the separate word would). To convey this meaning, Greek may use ἄν (e.g. 1 Cor 2:8; see ## for more on the meaning of ἄν) or future participles or infinitives (e.g. Jn 6:64; see ##). Other languages might have a true prospective aspect where the meaning represented in is encoded in a verbal form (Karuk and Tlingit are two such languages this has been proposed for). However, this brings us back to a crucial point. All of the tenses as well as aspects that we have discussed are logical relationships between temporal intervals or points, and these relationships need not necessarily be encoded by a single morpheme in a given language. The diagrams represent interpretations or readings of verb forms and not necessarily the meaning encoded by the forms. In some cases, the notional category may line up with a morpheme in a language, as we have suggested for tense with the Luo form (present tense) and the Aorist (past tense). In reality, it would be more parsimonious for a language system not to include a morpheme for every possible temporal relationship. Instead of having a specific morpheme encode for past, present, and future, some languages, for example, only have a past and non-past. This is not to say that in these languages speakers cannot or do not distinguish between eventualities that happen in the present and those that happen in the future. These interpretations are, of course, available in every language. They simply may use other means, such as adverbs (e.g. later), modal markers (e.g. will), or the nature of the eventuality to distinguish between present and future time (e.g. perfective readings disprefer the present). In such languages, we cannot speak of a strict future tense, i.e. a morpheme that encodes the meaning found in the diagram above. Rather, that notional category is conveyed by a combination of morphemes.

The contrast between perfective and imperfective is often similarly indicated in many languages, including in Greek. Whereas perfective aspect seems to be marked by the aorist, imperfective aspect has no marking. From a morphological standpoint, this is a matter of fact: the aorist ἔνευσα has the -σ- that is found throughout the system as a perfective marker, and the corresponding imperfective is not marked at all. This marking is not merely a phonological difference, however. The aorist seems to require that a temporal boundary of the ET is included in the RT (see ##). What is often called the imperfective forms, on the other hand (the Luo and Eluon forms or the “present” stem), has no such requirement, but moreover, it does not require that the ET extend beyond the RT. In other words, it does not actually encode imperfective aspect (at least as represented by ), as the following example demonstrates where a boundary is included in the RT (repeated from above):

- ἔρχεται Ἰησοῦς καὶ λαμβάνει τὸν ἄρτον καὶ δίδωσιν αὐτοῖς

‘Jesus comes and takes the bread and gives (it) to them.’ (Jn 21:13)

In another chapter, we said that this was an example of the historical present, and we gave further justification for this analysis above. Elsewhere, we also said that this was an example of a culminating interpretation. Jesus is not described as being in the midst of coming and taking the bread and giving it to his disciples—the narrative presents these events as happening in succession and each as ending one after the other. Narrative progression is one of the hallmarks of a perfective interpretation. In other words, this is a perfective interpretation of the Luo form.

The above examples show that the notional category of imperfective aspect is not expressed in Greek with a particular morpheme, at least if we define imperfective in the way that we have done (with the ET extending beyond the RT). We are again left with a conundrum—do we abandon the imperfective analysis of the Luo form, or do we revise our definition of imperfective? There is reason to again take the latter route in this case, just as we did for the present tense. In a language like English, we do not mark perfective aspect, but we do seem to mark what we called “imperfective” aspect above. The sentence Nick was running the race forces us to view only part of the event. Notice, that was running adds an additional morpheme, namely be + –ing (this form is normally called a progressive rather than imperfective). Koine Greek does the opposite. Instead of adding an additional morpheme for the imperfective-like meaning, an additional morpheme, namely -σ-, is added for the perfective meaning. Indeed, we have said that the aorist always includes a temporal boundary, but the counterpart form, Eluon, may also include a temporal boundary but need not. Indeed, aspectologist Daniel Altshuler (2014:739) defines imperfective aspect in precisely this way when he says that imperfective aspect “requires a stage of an event…but this stage need not be maximal” (italics original). This allows the imperfective to have a culminating interpretation when the event being described has only one “stage” (a technical term in Altshuler’s theory whose technical definition need not concern us here). Defining imperfective in this way accounts for the distribution of the Luo and Eluon forms in Greek: they are interpreted identically to the perfective aorist in some contexts, but these are limited to certain verb classes, and they also may receive the opposite interpretation, namely with the ET extending beyond the RT. The Luo and Eluon forms are imperfective in Altshuler’s sense in that they are only require a stage of an event and this stage need not be maximal, but they are not imperfective in the sense that the required interpretation is that the ET extends beyond the RT (the semantics of which better reflects the English progressive form).

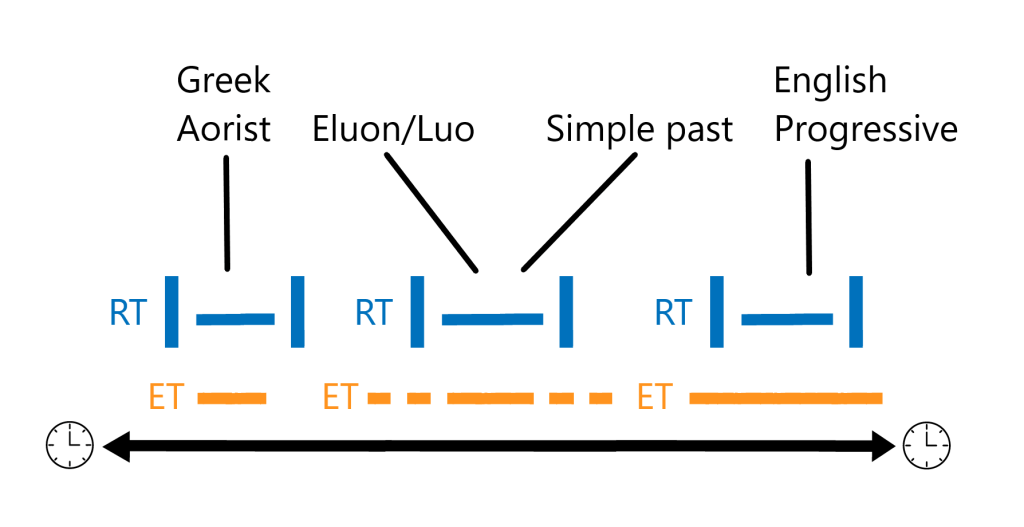

Before concluding this section, it is worth fleshing out the differences between the English and Greek aspectual systems. While the English progressive (be + –ing) cannot refer to a temporal boundary, the Greek aorist necessarily refers to a temporal boundary, and both languages have forms in the middle (namely the English simple past, –ed, and the Greek Eluon) that may or may not refer to a temporal boundary. Because of how the different systems mark temporal boundaries, there will not be a one-to-one relationship between any of the forms. The imperfective forms in Greek, namely Luo and Eluon, may map onto either the progressive or the simple past/present tenses. In contrast, the aorist may map onto the simple past tense, but the prediction is that it will not map onto the English progressive form. The following diagram shows the relationships between the forms in the two languages (with the dotted ET in the middle diagram representing a possible imperfective interpretation).

Figure 9: Comparison between Greek’s and English’s Aspectual Systems

The diagram superficially suggests a tighter relationship between the Greek luo form and the English simple past than we find in the data. While there is overlap between the two, luo is often interpreted like a progressive, and the English simple past is often interpreted like a perfective. This is, I suggest, due to what the two imperfective forms are contrasted with. In the Greek system, the imperfective is contrasted with a form that requires a temporal boundary. The imperfective, then, is the only form that can be interpreted with no temporal boundary, so it often receives a progressive-like interpretation. In contrast, the English system has an imperfective contrasted with a progressive. Because the progressive cannot refer to a temporal boundary, the imperfective is the only form that can, so it often receives a perfective-like interpretation. This not only explains the occasional overlap between the Greek luo/eluon and English simple present/past, but it also explains the frequent opposite distribution, despite both forms having the same meaning.

Besides the imperfective/perfective distinction, Greek’s Leluka form also allows for a variety of readings. However, these readings are best explained in light of how certain verbal predicates combine with the form, which brings us to the category of aktionsart.

Aktionsart

Thus far, we have discussed tense and aspect as relationships between the TA, ET, and RT. We mentioned briefly that the TA is normally a point in time, namely the moment of speaking, and the RT can be either a point or an interval, since we can talk about what happened at 5 PM or between 4-5 PM. The ET is fundamentally different from the TA and the RT because eventualities have more diverse properties besides being a point or an interval. Even the distinction between an event and state, which is how we defined the term eventuality, is not about length of time—it is about the nature of what is going on during a certain time. This is encoded in the nature of the verb itself, and it interacts with the grammar in significant ways, as demonstrated by the following examples:

- a. *I am knowing Greek.

b. I am learning Greek.

It has long been noticed that the English progressive form does not combine with some types of states in a straightforward way (though as with everything else, this has been nuanced in various ways). Such facts about how verbs interact with grammatical aspect have led to the classification of verbs into categories with different features. This is what aktionsart is—it describes the properties of verbal descriptions of eventualities. The basic classification of eventualities goes back to the philosopher Zeno Vendler (1957) who came up with the following system:

Table: Aktionsart values from Vendler (1957)

| Class | Durative | Telic | Dynamic |

| State | + | – | – |

| Activity | + | – | + |

| Accomplishment | + | + | + |

| Achievement | – | + | + |

Linguists have since modified these classes in various ways, and we cannot begin to survey all the current theories in linguistics. However, there are two foundational elements to aktionsart that are crucial for interpretation. First, although verbs themselves do indeed have certain properties, the nature of the eventuality that the verb refers to is also affected by the argument(s) that the verb combines with. The following contrast illustrates this:

- a. We built a Lego house in 2 hours/*for 2 hours.

b. We built Lego houses *in 2 hours/for 2 hours.

The only difference between the two sentences in is the object. In (a), the object of built is a Lego house with a singular noun and an indefinite article. In (b), we have the bare plural Lego houses, i.e. a plural without an article. While the sentence in (a) naturally combines with an in-adverbial, such as in 2 hours, it is odd to have it combine with a for-adverbial, as in for 2 hours. The opposite holds for the (b) sentence with the bare plural. This and other similar facts have led linguists to speak of aktionsart as a property of the entire predicate (the verb and its arguments) rather than a property of the verb alone.

Before coming to how all of this is relevant for Greek, one more foundational concept must be discussed. Since we have defined aspect as the relationship between the ET and the RT, we should expect that changing the ET could affect the aspectual interpretation of the clause—indeed, this is the case. This is clearly seen in the five readings of the perfect, as discussed in Kiparsky (2000:###) and to which we return below in discussion of the Greek Leluka form. Clauses in the perfect can have different interpretations, and certain interpretations are made possible or more or less salient depending on the nature of the predicate. One interpretation, for example, is the universal perfect. In this interpretation of the perfect, a state started in the past and continues to hold in the present moment, as illustrated in :

- Lydia has lived in Philippi for seven years, and indeed she still lives there.

Notice that this reading of the perfect requires a state, such as live. If we change the verb to an event like visit as in Lydia has visited Philippi, the universal perfect reading is no longer possible, since visit is not a state that can hold in the present. If we take out the length of the state so that we only have Lydia has lived in Philippi, we again lose the universal perfect interpretation. What this illustrates is that the interpretation of the perfect aspect is sensitive to the kinds of predicates that it combines with.

And this brings us to the Greek Leluka form. There are all kinds of definitions given for Leluka, and it is often called “exegetically significant.” Because some scholars have different views of what aspect is (see fn. ��71�), the task of trying to figure out what everyone is saying is quite daunting. As we point out below, the common definition of “past action with continuing results” only describes a particular interpretation of the form, and it has created a tremendous amount of confusion. Rather than bog down the reader with the various scholarly discussions, we point out here some of the common errors made in exegesis with the Leluka form that need to be corrected, and we show how the aktionsart of the predicate can help us to predict the interpretation of the form.

Statements like the following on the “significance” of Leluka are commonplace: “and the perfect tense emphasizing that a decisive act has already taken place which has proved to be the eschatological turning point in the history of salvation” (Dunn, Romans:165). Dunn is here commenting on πεφανέρωται in Rom 3:21. My point here is simple: the perfect does not “emphasize” that a “decisive act” has taken place; it contributes a temporal relationship. With this particular verb, the perfect is used to refer to the result state of the event of revealing. Given that it is the righteousness of God that has been revealed in Rom 3:21, it is indeed a significant thing that has been revealed, but the perfect could just as easily be used in a sentence like ὁ ἄρτος πεφανέρωται where a loaf of bread has been revealed at a dinner table. This need not be a “decisive act,” and the perfect in a sentence like this just means that the bread is now in the state of being visible and was not so before the event occurred. The point here is that the perfect is not particularly special. Sometimes it is used in significant contexts. Other times it is not—just like every other verbal form.

In linguistics, the perfect continues to generate debate about how precisely to characterize the temporal relationship it encodes. Part of the reason for this is that perfects across languages have different ranges of meaning. Like most areas of grammar, the English perfect (represented by the have + –en form) has received the most attention, and there have been 3 primary readings of the perfect that have been noted: the result perfect, the universal perfect, and the existential perfect. Returning to our example with Lydia, the sentence Lydia has visited Philippi is ambiguous between the result perfect reading and the existential reading. If I am in Philippi and excited about seeing Lydia who I know has just come, I might utter the sentence Lydia has visited Philippi meaning that she is now in Philippi. This is the result perfect reading where Lydia is in the result state of having visited a place, i.e. she is in that place. In another context, the existential reading is salient. If I am talking to someone in Ephesus about all the places Lydia has visited in Greece, I might say Lydia has visited Philippi meaning she has visited the city at some point in the past. This is the existential reading where an event occurred that is relevant to the current discussion, but there is no natural result state of the event that holds in the present moment. As we have said, the universal perfect reading is demonstrated by Lydia has lived in Philippi for seven years (and indeed, she still lives there). This represents a past state that continues to hold in the present.

The Greek perfect has all three of these readings in addition to two other readings that are marginal at best in English. Discussions of each of the individual readings can be found in the following sections: result , existential , universal , stative , perfective . For convenience, examples from each of the sections are given here as well:

- Result perfect

ἰδοὺ τὸ ἄριστόν μου ἡτοίμακα

‘Look, I have prepared my dinner.’ (Matt 22:4)

- Existential perfect

ἑωράκαμεν τὸν κύριον

‘We have seen the lord.’ (Jn 20:25)

- Universal perfect

τί ὧδε ἑστήκατε ὅλην τὴν ἡμέραν ἀργοί;

‘Why have you stood here all day idle?’ (Matt 20:6)

- Stative perfect

οἶδα ὅτι Μεσσίας ἔρχεται ὁ λεγόμενος χριστός

‘I know that the Messiah is coming, the one called the Christ.’ (Jn 4:25)

- Perfective

καὶ ἦλθεν καὶ εἴληφεν ἐκ τῆς δεξιᾶς τοῦ καθημένου ἐπὶ τοῦ θρόνου

‘And he went and took from the right hand of the one sitting on the throne.’ (Rev 5:7)

Each of the readings of the perfect, except for the perfective, have the same basic temporal structure. At least part of the eventuality named by the verb precedes the RT. In the result perfect, the verb refers to a state-event combination where the event causes the state. Once the dinner has been prepared in Matt 22:4, it is in the state of being ‘ready.’ In the existential perfect, the verb names an event or state that is not related to another event or state. The RT follows the eventuality but does not refer to an event or state connected with that eventuality. The verb ὁράω ‘see’ does not have any consequent state naturally connected to it. Saying you have seen something simply means that you have engaged in that event at some point prior to the time under discussion, and this event of seeing is relevant in some way to the current discussion, as it is in Jn 20:25. In the universal perfect, the state holds prior to the RT and extends into the RT itself. The lazy fieldworkers in Matt 20:6 were standing there idle all day, and when they are rebuked, they are still standing there idle (until they go into the field in the next verse). In the stative perfect, the verb names a state that implies a prior event. The woman at the well in John 4:25 knows that the Messiah is coming, implying that she learned that at some point prior to her knowledge. Temporal diagrams showing temporal precedence can depict each of these readings:

Figure 10: Result Perfect Temporal Structure

Figure 11: Existential Perfect Temporal Structure

Figure 12: Universal Perfect Temporal Structure

Figure 13: Stative Perfect Temporal Structure

The final reading of the Leluka form, namely the perfective, differs in that an analysis where the ET precedes the RT does not work. (It is, however, similar to the existential perfect in that there need be no natural consequent state to the eventuality the verb refers to.) In Rev 5:7, the Leluka form follows an aorist and seems to be the next event in a sequence of events, a typical function of perfective forms. Again, this is where our notional categories are not lining up with the meaning encoded by a particular verbal form in a language. This is the challenge of doing semantics. Notably, the perfective reading seems to be a recent development. It is only found rarely in the NT, and in later periods of Koine, the Leluka form will merge with the aorist and more regularly express the perfective reading. In other works (Grasso: forthcoming), I have provided a semantic explanation and extensive discussion on the meaning of the Biblical Hebrew Qatal form, and I have suggested that the Greek Leluka form essentially has the same meaning. Those interested can find more discussion there. What remains is to summarize how the interpretations of Leluka interact with different kinds of verbal predicates. These are given in the following chart:

| Aktionsart of predicate |

| Result Perfect | [+ Telic] |

| Existential Perfect | Any eventuality |

| Universal Perfect | [+ Stative] [+ Duration specified] |

| Stative Perfect | [+ Stative] |

| Perfective | [+ Event] |

The purpose of this chart is to show how aktionsart and aspect interact to produce a given interpretation. The result perfect is, by definition, a state that holds on account of a prior event. Thus, this interpretation requires a [+ Telic] aktionsart for the predicate because the result of the event needs to be specified, it being explicitly referred to in the interpretation. The existential perfect is unique in that it does not place any particular demands on the kinds of predicate, though eventive verbs will normally receive the existential interpretation (particularly because the perfective reading is not common in Koine). The universal reading requires a state, but it also requires the duration of the state to be explicitly given. The stative perfect requires a stative predicate, and the perfective requires an eventive predicate. It must be noted that it is rarely the case that you can determine the interpretation from the nature of the predicate alone. The chart provided helps you to rule out certain interpretations, but it never tells you how to interpret any given instance of the perfect. A predicate that is [+ Telic], for example, might be a result perfect, but it could also be an existential or even (rarely) a perfective. Likewise, even a stative predicate with the duration specified could be an existential, universal, or stative perfect. You cannot, therefore, conclude that a certain aktionsart value will always lead to a particular interpretation, but the chart can help you to narrow down the options.

This discussion has barely scratched the surface of tense and aspect studies in linguistics. It is not without reason that Kai von Fintel describes the semantics of tense and aspect (along with determiners and quantifiers) as the “bread and butter of working semanticists” (1995:177-178). Two final words of caution are then needed. First, do not equate verbal forms with pragmatic functions like “importance” or “emphasis.” They refer to temporal relationships; their “exegetical significance” should not be overplayed. Second, do not jump to conclusions. The reason why working semanticists make a living off of analyzing tense and aspect is because it is complicated. Our analyses are almost always incomplete, and our descriptions can almost always be refined more accurately.

Footnotes

Porter calls aspect fundamentally “perspectival” and says that there is agreement on it with NT studies: “it is also commonly agreed [between Porter, Campbell, and Fanning] that verbal aspect is perspectival in nature, that is, that it is concerned with a grammatical means of enshrining authorial perspectives on processes…Verbal aspect is not itself a temporal or a spatial/locational category, even if it is related to them…” (2020:109). Campbell emphasizes that aspect is “spatial” rather than “perspectival” and again says that there is agreement on this within NT Greek grammatical studies: “There are other areas of agreement as well: Aspect is defined as viewpoint, which is a spatial rather than temporal concept” (emphasis original; Campbell 2024:26). That the scholars who have written most about aspect in NT studies do not define aspect as would be taught in any introductory semantics class shows the widespread confusion on this issue. Semanticists do not debate about what aspect is fundamentally—it is temporal.

For a sampling of important works within linguistics that define aspect temporally as well as a critique of Campbell/Porter’s position on aspect, see Biblingo’s blog and podcast series reviewing Campbell’s Basics of Verbal Aspect in Biblical Greek.

In linguistics, there are two sets of terminologies floating around that essentially refer to the same time intervals. The (neo)-Reichenbachian system uses the terms Speech Time (ST), Reference Time (RT), and Event Time (ET). The (neo)-Kleinian system uses the terms Time of Utterance (TU), Topic Time (TT), and Time of Situation (TSit), which correspond to the same three temporal intervals. In later work, Klein replaces TU with Temporal Anchor (TA; ###), recognizing that the TA is not always the same as the TU/ST. I follow this distinction here, though I adopt the Reichenbachian terms for the other times because they are more common and seem to be slightly easier to understand for students.

For a recent discussion where copious references can be found to how this has been treated in the semantics literature, see Pancheva & Zubizarreta (2023:8-11).

Give examples and references ###

Give a spattering of examples ###

This is not to say that all who reject the Luo form as a true present tense have the wrong definition of tense. A notable exception is Olsen (1995). She says that neither Luo nor the Aorist are true tenses, and she presents about a dozen examples that are supposed to show that the tense analysis is untenable (1995:279-290). However, all of her examples have logical semantic explanations. To illustrate, she notes that over 50% of the Luo verbs with past reference are verbs of speaking, most being λέγω. The fact that a particular verb class is far more common than others for past reference suggests that there is some meaning component in verbs of speaking that allows it to be used in those contexts more readily. Indeed, verbs of speaking like λέγω are commonly use as complementizers to content (Bassel 2022), and when they do so, their tense value may be bleached (wals.info/chapter/128). Verbs of speaking are also unique syntactically in English. Just as we cannot conclude that English has no default word order because of examples like ‘That’s not correct,’ said Sylvia (where said Sylvia is VS order, and English normally defaults to SV), so we cannot conclude that the Luo form is not a true present tense if there is a particular verb class that behaves differently. Space precludes going through all the other kinds of examples, but none are surprising given how present tense forms are used across languages (again see Pancheva & Zubizarreta 2023 for a discussion).

For a recent introduction to the debate, see Campbell’s (2024) excursus More Tense Discussion.

Of course, eventualities are themselves linguistically defined. While the length of a building house event is a fact about the world, that we can even speak of the length of time it takes to build a house is dependent upon what we mean by build a house.

Even those that have temporal definitions of aspect within NT studies typically do not distinguish the imperfective and progressive meanings and, therefore, cannot account for the culminating interpretations of the imperfective forms in their semantics. For example, Thomson’s (2016) important contribution in The Greek Verb Revisited presents imperfective aspect as if it required the ET to extend beyond the RT. If we define the notional category of imperfective aspect in this way, the Luo and Eluon forms are not imperfective aspect. The problem is that in the literature, the term “imperfective” is often used for the interpretation of ET extending beyond RT, but it is also used to refer to forms that do not necessarily always have that interpretation.

Some within NT Greek grammatical studies talk about aktionsart as if it is the interpretation of a clause or what happens in the actual world (Campbell 2024). Again, this is not how the term is used in linguistics. For how the term is used in linguistics, see Kroeger’s Analyzing Meaning (2022:376-82) or any other introductory semantics textbook.

For an introduction of some of the issues today, see Filip (2012: Oxford Handbook).

In syntactic terms, we could speak of the verb (V) and the verb phrase (VP). Aktionsart is a property of VPs, even though the verb itself is, of course, the central part of determining the nature of the VP.

For a lucid discussion of many of the issues in the field as well as a description using the standard linguistics definition of aspect, see Crellin (2016: Greek verb revisited).

Two other readings of the perfect are often given. First, the recent past reading in a sentence like The cubs have won the World Series is often noted. This is usually subsumed under the result perfect or existential perfect. The other reading, which is marginal in English, is the present stative reading in a sentence like I’ve got five dollars in my pocket. This interpretation only seems possible with the cliticized –‘ve form, and I do not know if it is possible with verbs besides get. Because of this limited distribution in English, the pure state reading has received little attention in the literature.

This analysis of the pure stative reading suggests that it is only states that imply prior events that work with this reading. Another analysis would be to say that the pure state reading is the original meaning of the perfect, and the other uses arose from non-states beginning to combine with the form. For the implementation of such an analysis, see Grasso (forthcoming).

For discussion of why this happens and the implications, see Moser (2016:550-554) and Horrocks (2010:176-178).

Like this:

Like Loading...

Related