We have already said that English’s aspectual system is indeed different from Greek, but we should not be surprised that Greek can make aspectual distinctions in the subjunctive mood. I am sure Ancient Greeks would have been bewildered by the four different aspectual forms that can all combine with the several different modal forms we have in modern English! Our system is different, but it is certainly not less complex–if anything, it is more. I say this to draw attention to the fact that we have to be more self-reflective about our own language. I am sure Campbell has used the ‘might have been doing’ combination in his own use of English. I am certainly not suggesting he is bad at using English, but analysis is a different animal. It is much harder to be self-reflective about our own language use, but this would greatly help us in our analysis of other languages, such as Greek. The historical present is another case in point. If English, as well as language after language, has the same construction, we should not be surprised if Greek does, but we should also then carefully consider the best way the Greek historical present maps onto English. Since English does have this use of the present and it is arguably used to signal a very similar meaning, we should try to reflect this in our translation, and indeed, many times we can if we are thinking critically about how our own language works.

Finally, I want to briefly go back to the principle of compositionality that I mentioned in the beginning of this video. The principle says that the meaning of a complex expression is equivalent to the meaning of its component parts and how they combine. Campbell himself used the four-box method to try to determine the meaning of a complex expression, and I said that this is indeed the correct way to go about it, even if Campbell’s equations were incorrect. When Campbell comes to the non-indicative forms in chapters 10-11, he does not define each of the different categories he treats, and he says that the four-box method is no longer relevant. It seems unclear to me whether he thinks such a method simply does not work for the non-indicative moods or if he omits the four boxes only for the “sake of simplicity” (which he does mention). Regardless, I propose that thinking compositionally about the meaning is indeed still the correct way to go about the analysis.

So when we come to the non-indicative forms in chapters 10-11, we would ideally want to see clear definitions for each of the other meaning components, and then we can see how these meaning components combine with the different aspects. For example, we need a definition of the subjunctive. When we combine the meaning of the subjunctive with the meaning of the aorist with the meaning of the particular verb, we should get the meaning of that subjunctive aorist verb. Campbell nowhere provides a meaning for the subjunctive, infinitive, imperative, or participle. I understand that this is an introductory book, so the definition may need to be simplified, but it still needs to be given. We need to know what these things are in order to analyze them. Only in having such a definition can we evaluate whether the theory can make the correct predictions. This is what we are trying to do in semantic analysis: provide a meaning for each morpheme in a sentence that would correctly predict the meaning of a novel sentence. What makes this complex is that there are a lot of different meaning components that we need to take into account, and it is sometimes difficult to know which meaning components are relevant. We saw this in our discussion of the conative use of the imperfect. That interpretation was only present with certain kinds of verbs, namely achievements, with certain kinds of subjects, namely animate, and we gave reasons why achievement predicates and animate subjects were necessary conditions for that interpretation. Even something like the animacy of the subject can affect the temporal structure of the event being referred to. Language is indeed complex, and the complexity demands our humility. This is evident to all who have ventured into the world of natural language semantics.

Finally, we come to the appendix where Campbell treats the Greek Verb Revisited. As I said for Campbell’s review of the field of Greek grammatical studies in chapter 2, I do not want to just evaluate Campbell’s evaluation of others, and I am not here to defend one side against the other. However, Campbell does make a few points about linguistics that I want to touch on briefly (if you have stuck with me this far, I promise it will be brief).

First, Campbell applauds the volume’s “common embrace of a cognitive approach.” I am not against cognitive linguistics per se, but it is odd that a cognitive approach would be applauded about a book on the verbal system of a language when it is formal semanticists, not cognitive semanticists, that have done the most work on tense and aspect markers. Since Campbell is endorsing a cognitive linguistics approach as do the authors of the “Greek Verb Revisited,” this comment applies to both parties. Within biblical studies, cognitive linguistics is often treated like the dominant, dare I say the only, linguistic paradigm. Again, this is a failure to read the linguistics literature itself. Generative grammar and formal semantics dominate linguistics worldwide. If you Google the best linguistics universities in the world, you will consistently find Stanford, Harvard, and MIT at the top. All of these programs are dominated by formal semanticists and syntacticians, and it is scholars in the formal approaches that have done the most work on tense and aspect. There is a reason why Kai Von Fintel, linguist at MIT, says that tense and aspect are the “bread and butter of the working semanticist.” It’s because these are the kinds of things they obsess over. They have given us all the nuanced definitions of tense and aspect that are operative today. If we could describe the main areas of study in both cognitive semantics and formal semantics, the former would be primarily concerned with the meaning of lexical items, and the latter would be primarily concerned with grammatical items. If you know the field, you know that there is more to it than this, but that would be the basic split. Tense and aspect markers are grammatical. That is the main domain of formal semanticists. Some such scholars are cited in certain papers in the Greek Verb Revisited, so I am not addressing everyone who wrote those papers, nor am I only addressing Campbell who is applauding the cognitive approach. My point here is more to address the broader issue within biblical studies that the field of linguistics is often simply misunderstood. If an outsider to the field of theology and biblical studies looked at how scholars used Hebrew, but they only read the scholars who were New Testament theologians, they would get a very skewed view of the field. Hebrew is not their thing. Likewise, if you read only scholars working in cognitive linguistics and try to build your definition of tense and aspect off of these scholars alone, you are going to get a skewed view of the field. I will demonstrate this shortly with a real issue that Campbell brings up.

Before this, I do want to touch on some of Campbell’s claims in section 3 of the appendix entitled “The Hegemony of Linguistics.” In this section, Campbell essentially argues that linguistics has something to offer, but Greek grammarians may disagree with them and be correct. This is true. One of the reasons why I have gone through the data in these reviews is that our theories are indeed about how we interpret the data. In theory, Greek scholars may all disagree with linguists about how to define tense and aspect, and they may have a better reading of the data. I have tried to show that this, however, is false. The field of linguistics offers us better tools to understand the data. However, more is being claimed in this section. Campbell says things about the field of linguistics that are false. He says, “Besides, we [Porter, Fanning, and Campbell] are not naively unaware of alternate definitions of aspect, as found in Bernard Comrie and others. Instead, our understanding of aspect as viewpoint is consistent with the history of the discussion, both within and outside Greek studies. Comrie in 1975 stepped away from that trajectory by analyzing aspect in temporal terms.” The great irony of this statement is that Comrie is himself not a semanticist. He is a typologist. Typologists generally answer the question, “What do a large swath of languages do,” rather than the question of the semanticist, “What exactly does this mean,” and certainly not the narrower question of the aspectologist, “What exactly do aspect markers mean?” He was not breaking new ground with his theory of aspect in 1976, as suggested by Campbell. Again, Campbell makes an incorrect statement about linguistics here with zero citations.

Robert Binnick’s book, Time and the Verb, does provide us with the historical context of Comrie’s book on aspect (to which he pays only moderate attention because, again, though I recommend Comrie’s little book on aspect for beginners, he is himself not a semanticist). He gives the most thorough historical treatment of tense and aspect studies, beginning with the ancient Greeks leading all the way up to the early 1990s (when the book was written). Regarding ancient grammarians, he says, “The Stoics are generally considered…to have essentially originated the Varronian theory, and to have observed an aspectual distinction (complete vs. incomplete action) crosscutting the purely temporal one of past and present.” It is debated whether the Stoic theory has its roots in Dionysius Thrax, the famous 2nd century BC Greek grammarian, but regardless, it seems as though at least some ancient Greek grammarians were aware of aspectual distinctions. They also did not define it spatially but as essentially temporal, that is, it had to do with whether the action was viewed as complete or not. An incomplete event is, of course, reference to just part of the event. A complete event is reference to the whole event. This is not to say that the Stoics had the same aspectual theory as the modern field of aspectology, but they certainly said nothing about it being spatial, and you can see the roots of the modern theory in the Stoic-Varronian theory. Binnick also has a section on classical Greek grammarians and their view of aspect, to which I would refer you if you are interested in the history of the field, particularly placed in the context of the wider world of linguistics.

Elements of Symbolic Logic by Hans Reichenbach

Elements of Symbolic Logic by Hans ReichenbachThe most influential modern scholar who clarified and formalized the temporal concept of aspect is almost certainly the 20th century German philosopher Hans Reichenbach whose terms Speech Time, Reference Time, and Event Time are still in use today from his 1947 work “Elements of Symbolic Logic.”

Campbell’s discussion throughout this section simply fails to grapple with the linguistics literature, though claims about that literature are repeatedly made (again, without citations). It is true that, theoretically, New Testament Greek scholars might be correct, and all the aspectologists and typologists, all those making a living off of determining what aspect is and how it is encoded in the world’s languages, might be wrong. However, as I have tried to demonstrate, the linguistic theories are not just better because they are from linguistics. They are better because they account for the data. But the deeper issue is that Campbell does not cite any semanticists working on aspect in his entire book. The problem is that it does indeed seem that he is unacquainted with the people working on aspect in the linguistics world, and he misrepresents the field of linguistics to the world of biblical studies.

And so we come to our last discussion in, again, what has been a very long review. Campbell uses Langacker in support of his view of tense. In discussing Langacker’s view of tense, he says, “While Langacker retains the terms present-tense/past-tense for English, he says, ‘their fundamental semantic characterization pertains to epistemic distance.’ Now that sounds like a solution! And guess what–it is also the solution I have put forward with respect to Greek!” This discussion is about the problem of the past tense being used for counterfactual descriptions in Greek. In fact, this is common in a number of languages, including English, which is what Langacker is talking about. Campbell says that he is trying to say the same thing. If this is all that Campbell was trying to say with his “remoteness” terminology, I would happily agree with him. However, in Campbell’s discussion of the aorist form and the feature of remoteness, he never once mentions the counterfactual reading in chapter 3. The only example he gave in the chapter was Mark 1:11 where he discusses the verdict coming “from heaven.” Again, I do not know how to interpret Campbell’s description of this other than to say it is spatial, which is incorrect. He also talked about the aorist “covering a lot of ground” and presenting events as “less detailed.” In his list of uses of the aorist in chapter 8, Campbell does not even give counterfactual as an option, though he does say that the aorist can be present and future.

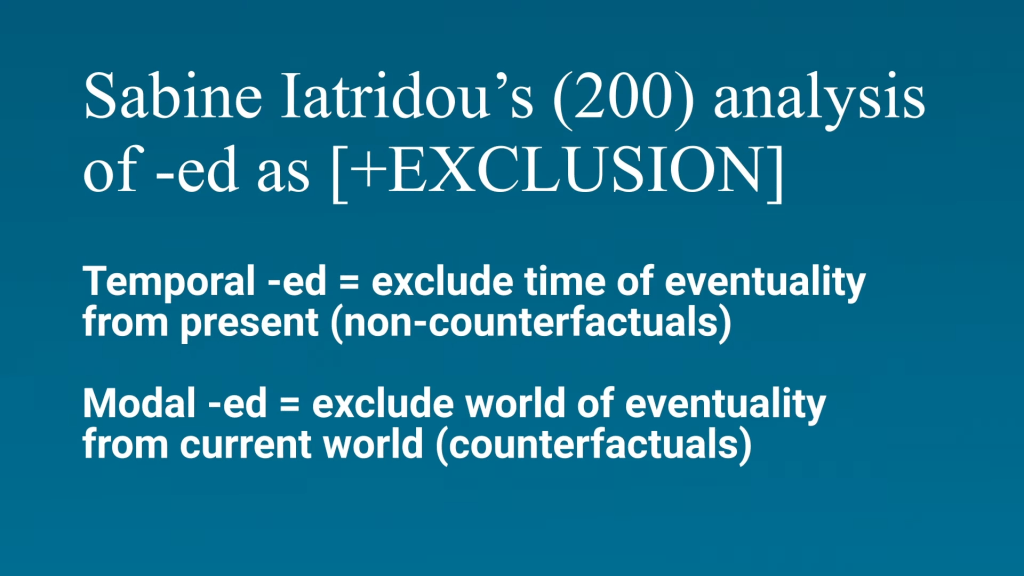

Again, the issue here is that the linguist Langacker is not saying what Campbell is saying he is saying. In the formal semantics literature, the Greek scholar Sabine Iatridou, a semantics professor from MIT, has worked on this problem in her article “The Grammatical Ingredients of Counterfactuality.” She essentially claims that, indeed, what we call the past tense morpheme is really not a past tense morpheme in the strict sense but is a morpheme that refers to an “exclusion feature.” The basic idea is that the morpheme -ed in English excludes something. Sometimes, the thing excluded is the topic time from the time of the speaker. This yields a past tense interpretation, since to exclude the time being discussed from the present time is to exclude it from the present moment. The counterfactual reading is treated in a very similar way except that we are no longer discussing times but possible worlds, which is the standard way of analyzing modals in semantics. In a counterfactual context, the world where the sentence is true is excluded from the world of the speaker, which is to say that the speaker considers the event description to be false. This unifies both uses of the past tense, so that we can have a single meaning, [+EXCLUSION], that accounts for all of its uses.