Chapters 7-9

Chapters 7-9 in Campbell’s book are all very similar. The basic structure of each chapter is to go through the uses of each of the forms and provide a sort of formula for how to get to the use by combining the semantics of the verbal lexeme with the semantics of the verbal form to get the interpretation. We will not go through every example, but I have picked uses from the imperfect, perfect, and present forms in order to demonstrate how to think through the issue of interpretation as a linguist would. As I said in my review of part 1, the details matter. We go into detail on a few passages in order to contrast Campbell’s analysis with that of modern linguistics. The three forms we discuss will demonstrate three linguistic or interpretive principles, namely compositionality, not reading meaning into the text, and mapping Greek onto English or another language, or in other words, translation.

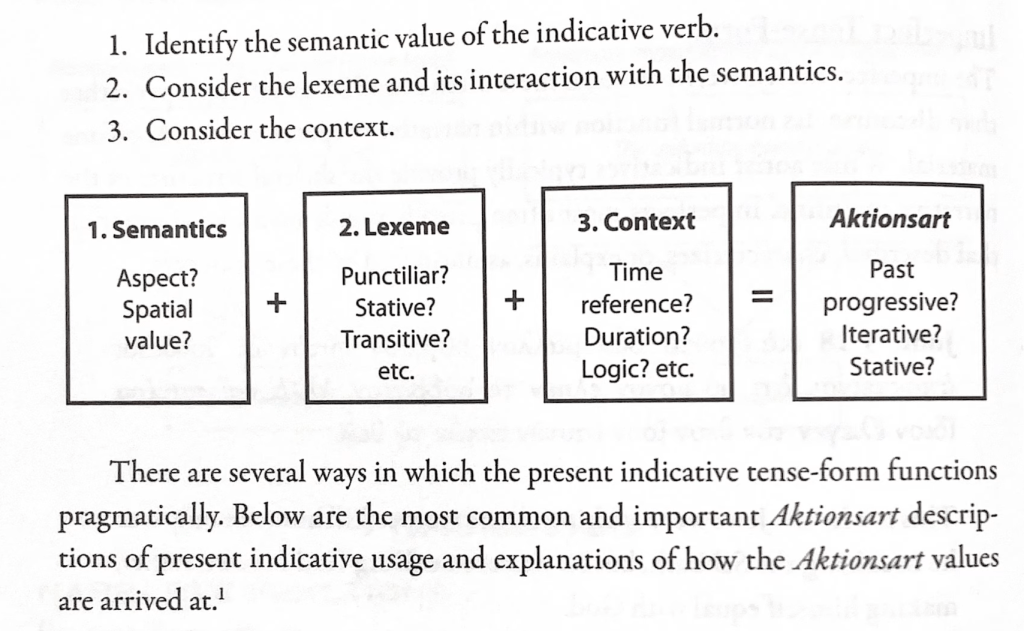

Again, it is important to clarify terms before we begin. Campbell has 4 boxes in the examples. He has semantics, lexeme, context, and aktionsart. Adding the first 3 is supposed to give you the fourth box, namely aktionsart.

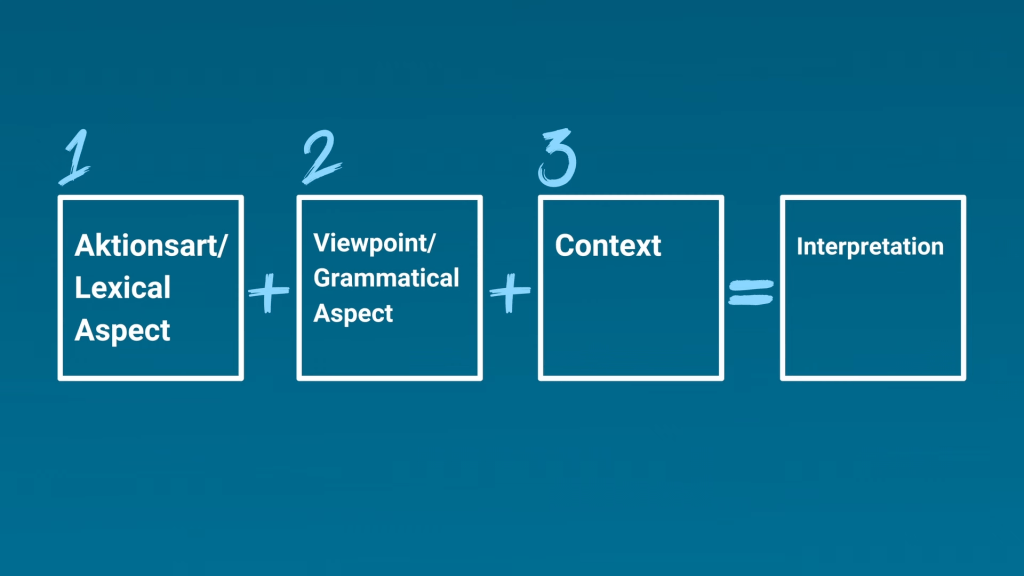

In linguistics, we would do something similar, but we would call the lexeme box aktionsart or lexical aspect, and the semantics box is really the semantics of the verbal form (which would include viewpoint/grammatical aspect and tense among potentially other categories). The context would be taken into consideration, but it would be done in a more systematic way.

The question with the context is, again, what does it actually refer to. We would want to be very specific about which meaningful elements in the context are affecting the interpretation of the form and why they are doing so.

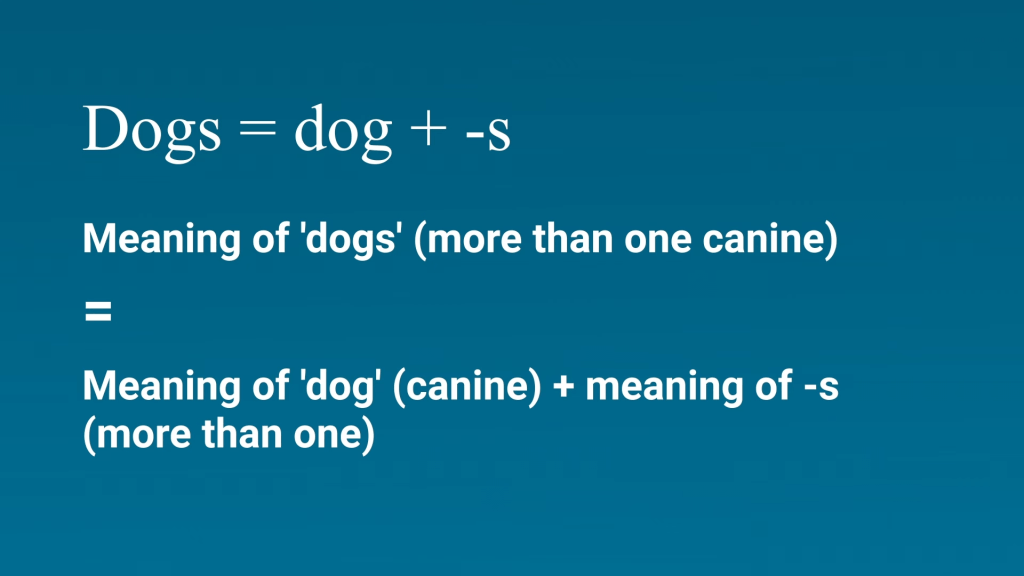

Let me say at the outset that I think Campbell’s approach here is correct. He is basically treating the semantics of the verbal forms like a math problem. If you add the semantics of the verbal form to the semantics of the predicate and also add whatever else is relevant in the context, you should end up with the correct interpretation. This seems to be Campell implicitly supporting the foundational idea of compositionality in semantics, which the mathematician-philosopher Gottlob Frege first articulated and applied to natural language in the late 1800s and early 1900s. The idea of compositionality is that the meaning of a complex expression is equivalent to the meaning of the individual parts and how they combine.

Let’s illustrate with a simple example. A word like ‘dogs’ is a complex expression in that it is made up of two morphemes, or meaningful elements. There is the word ‘dog’ plus the plural morpheme ‘-s’. The way we determine the meaning of this complex expression is by taking the meaning of ‘dog’ and combining it with the meaning of the ‘-s’, which yields more than one canine in this case.

What makes compositionality so powerful is that it allows us to predict the meaning of a new complex expression. For example, you might not know what a flabbit is, but when I say the complex expression ‘flabbits’, you know that there are more than one of whatever flabbit might refer to. This prediction comes from the idea of compositionality. By assigning a value to each individual morpheme and by combining morphemes in similar ways, we can determine the value of new complex expressions. Again, this is a foundational semantic concept that I think Campbell gets essentially correct, though he does not spell out the principle itself. Obviously, this idea gets much, much more complex, but without compositionality at some level, language would not work.

Some within New Testament studies don’t like to view language this way, so again, I think it is all the more important that Campbell’s method is affirmed here. As an anecdote, I remember Nijay Gupta’s response to a tweet Matt Bates made about my Pistis Christou paper when it first came out. He said something like language is not a math formula. Look, I have nothing against Nijay, but this does fly in the face of everyone working in the field of formal semantics. There is a reason why the best semanticists in the world often work at MIT or have their PhD from there. In many ways, language really is just a very complex math problem.

Now, I do not have an issue with the fact that Campbell is doing math, but with his equations. This brings us to the first verbal form to be discussed in this section, namely the imperfect and the conative use. We already gave the example from Mark 15:23 where Jesus is unsuccessfully “given” wine mixed with myrrh. Campbell lists this as a “conative” imperfect, or one that was not accomplished. We said that, indeed, that is the meaning here. This interpretation is generally accepted. Wallace lists the same verse in his grammar, Kostenberger, Merkle, and Plummer list the same verse in their intermediate grammar, and if there was another intermediate grammar in my vicinity at the moment, they would probably agree as well. And this is why I think many people struggle to find value in yet more discussions of the verbal system. If we all agree on the interpretation, what are we still doing talking about the meaning of verbs?

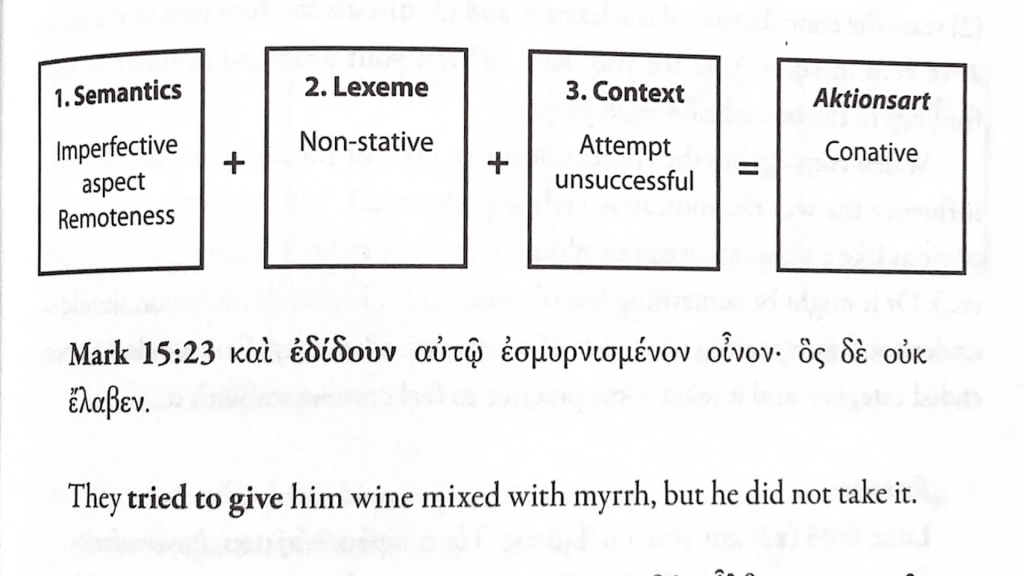

The utility in talking about how we got to the interpretation is that it allows us to predict the meaning in novel or debated contexts. This is the principle of compositionality in action, and it is where Campbell’s formulas matter. Everyone agrees that Mark 15:23 is a failed giving attempt (it explicitly says Jesus didn’t take the wine), but how can we predict this meaning in other, less clear contexts and not read the meaning into wrong contexts? Campbell’s formula for the conative interpretation is as follows: Imperfective aspect and Remoteness in verbal form + non-stative lexeme + attempt unsuccessful in context = Conative aktionsart.

Campbell defines imperfective aspect spatially. He has said that imperfective aspect gives a more detailed view of the event, while remoteness gives supplemental information. According to the equation, this can combine with any non-stative lexeme and yield the attempt unsuccessful interpretation. Notice in Campbell’s equation that he essentially gives the correct interpretation in the context box. What he calls the “aktionsart”, in this case “conative”, is really just the technical name for the interpretation he already supplies in the context. So basically, when the context denies that an action took place, the attempt was unsuccessful. This is rather obvious. The question that Campbell inadequately answers is how adding a form that gives a more detailed view of supplemental information to a non-stative lexeme would allow for this interpretation in the first place. In other words, it is not clear how all the things on the left side of the equation would add up to a conative interpretation other than the very obvious fact that if something in the context explicitly denies that the action took place, it didn’t take place. Our question is why this particular predicate and verbal form allow for what would otherwise be a contradiction. Why is the imperfect form used for this interpretation and not the aorist?

Our semantics of each of the elements in the sentence does explain this. The imperfective form specifies that one stage of the event took place. We know from languages like English that it is possible to refer to a pre-stage of an event with forms like the progressive, particularly when there is an intentional agent involved in the event. We already saw this in the sentence “Rhoda was arriving at platform 9 and 3 quarters” where the only stage of the event did not actually hold. The progressive, therefore, must only refer to a pre-stage of the actual event itself.

The verb δίδωμι only has one stage, namely the transference of possession. In Mark 15:23, the pre-stage of this event is referred to, and this satisfies the requirement we have given for the imperfective, which requires a single stage. The pre-stage here is the subject’s attempt to give the wine. We will come back to why this particular event description allows reference to a pre-stage momentarily, but the possibility of referring to a pre-stage is why the imperfective is not contradictory and why the aorist would be contradictory. The imperfective can refer to this pre-stage, but the aorist cannot, since it requires the endpoint of the event to have been reached.

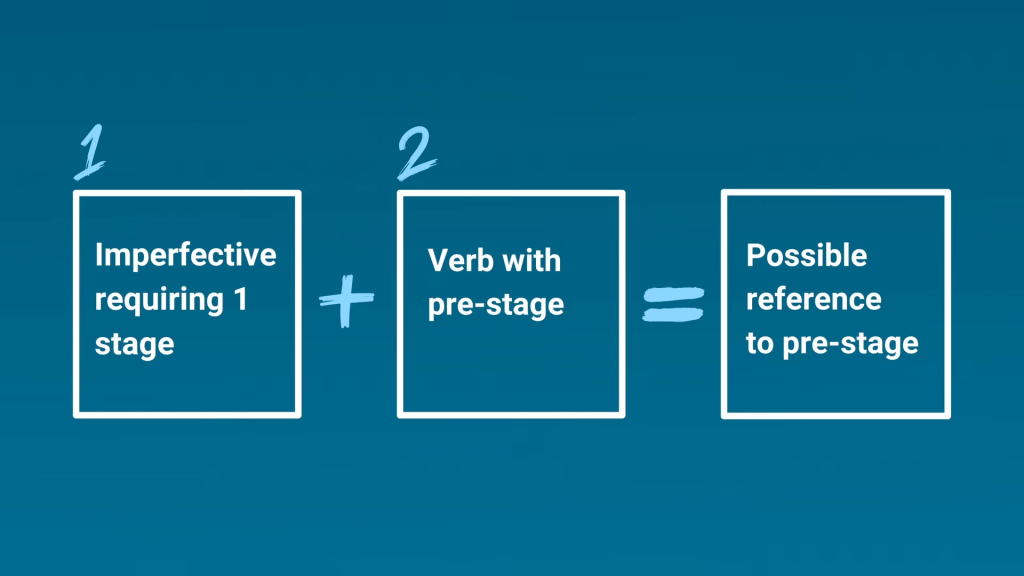

In other words, this offers an explanation for how we arrived at the actual interpretation. An imperfective form requiring one stage + a verb that has one stage but allows for reference to a pre-stage = a possible reference to the pre-stage of that event. In other words, a possible failed attempt of the event itself.

Since the next line specifies that the event did indeed fail, that is the correct interpretation.

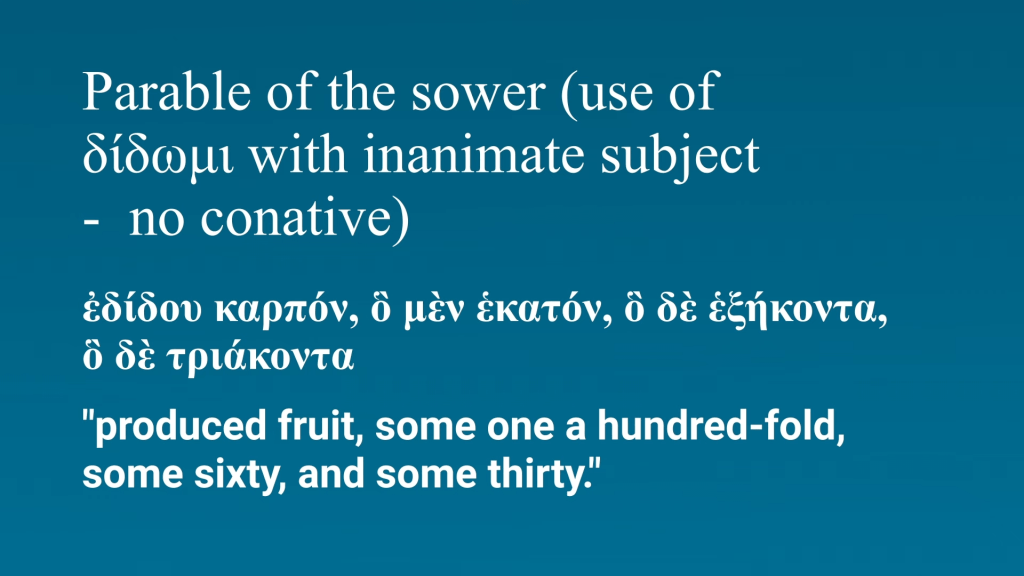

This analysis predicts that this interpretation is only available where a pre-stage of the event is possible. Work by linguist Fabienne Martin has shown that agentivity is the key meaning component required for reference to the pre-stage of an event in uses like the conative. A quick look at the data seems to suggest that this is indeed the case. All of Campbell’s examples as well as all of Wallace’s examples as well as all of Kostenberger, Merkle, and Plummer’s examples involve an animate subject. Why would an agentive human subject allow for this pre-stage use? When the subject is a person, that person can think about engaging in an event or attempt to engage in an event and fail. Reference to this pre-stage is not possible with inanimate subjects because they do not think about engaging in events and cannot attempt actions. Again, the Greek data reflects this. The imperfect of δίδωμι is found with inanimate subjects in the New Testament, but it never receives the conative interpretation where only the pre-stage of the event is referred to. For example, in the parable of the sower, it says that some seeds ἐδίδου καρπόν, ὃ μὲν ἑκατόν, ὃ δὲ ἑξήκοντα, ὃ δὲ τριάκοντα ‘produced fruit, some one a hundred-fold, some sixty, and some thirty.’

Notice, this statement entails that some fruit was actually produced by the seed. The conative interpretation of a failed event is impossible. When the imperfect is used in this context with an inanimate subject, the conative interpretation cannot hold. Our analysis predicts this.

This deep dive into one particular interpretation contrasts Campbell’s equation with how linguists would analyze this and illustrates the importance of the principle of compositionality. Whereas Campbell says that adding something spatial to a transitive verb might equal a possible failed attempt, we have given a real explanation for what is going on. A failed attempt is just reference to a pre-stage of the event actually taking place. We have given the conditions for reference to a pre-stage: an event with an animate subject. We have said there is only one verbal form that does not require the end of the event to be reached in Greek, and that is the imperfect. Thus, we predict that this interpretation is available for the imperfect form (and not for the aorist) when the pre-stage of the event is present based on the conditions we have given for it. If we are unable to infer from the context that the end of the event has been reached, we may interpret it as a failed attempt.

All of that is just to demonstrate how compositionality works with a real example. Of course, we cannot do this with every example Campbell gives in these three chapters, but honestly, we do not really have to. We have already said that his equations are necessarily wrong because aspectual forms are not spatial. We showed that in detail in part 1, and we have shown how his equation does not work with the conative interpretation. Before getting to the perfect and present forms and how their examples demonstrate the principles we are discussing, I want to give a high-level overview of the set of interpretations that Campbell gives as options for each of the forms.

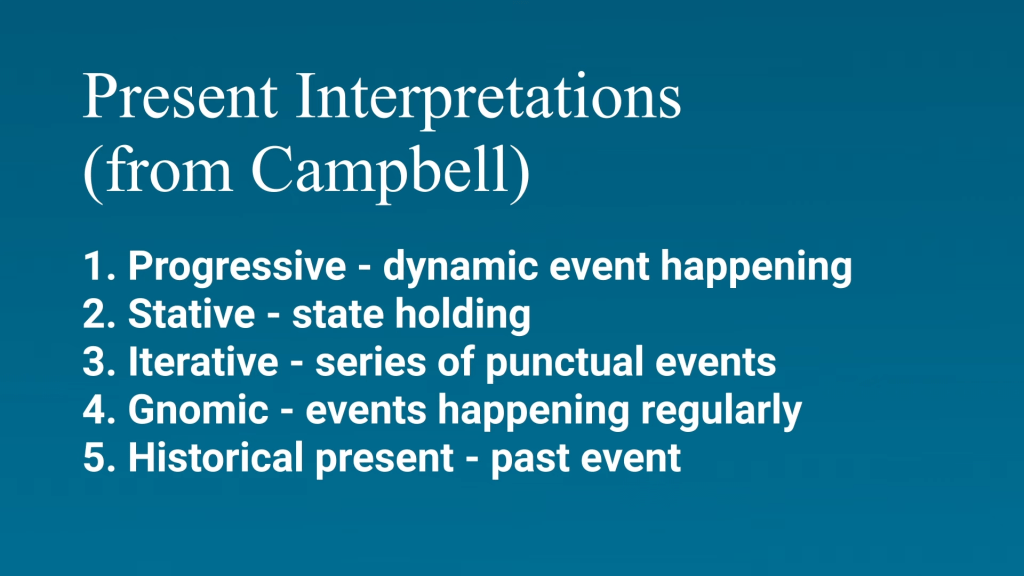

As I mentioned earlier, everyone agrees that there is such a thing as a conative interpretation of the imperfect, and everyone agrees for the most part on the verses that serve as good examples. But there is even more agreement than this. Despite Campbell giving a rather novel theory (rejecting temporality completely from the semantics of the verbal forms), he has more or less the same set of interpretations as everyone else for the verbal forms. And they are all temporal. For the present form, he gives progressive, stative, iterative, gnomic, and historical present. All of these are temporal interpretations: the progressive is a dynamic event happening during the reference time, the stative is a state holding during the reference time, an iterative is a series of punctual events occurring during the reference time, the gnomic is an event that occurs regularly during the reference time, and the historical present is when the temporal anchor has shifted to a past time in the story.

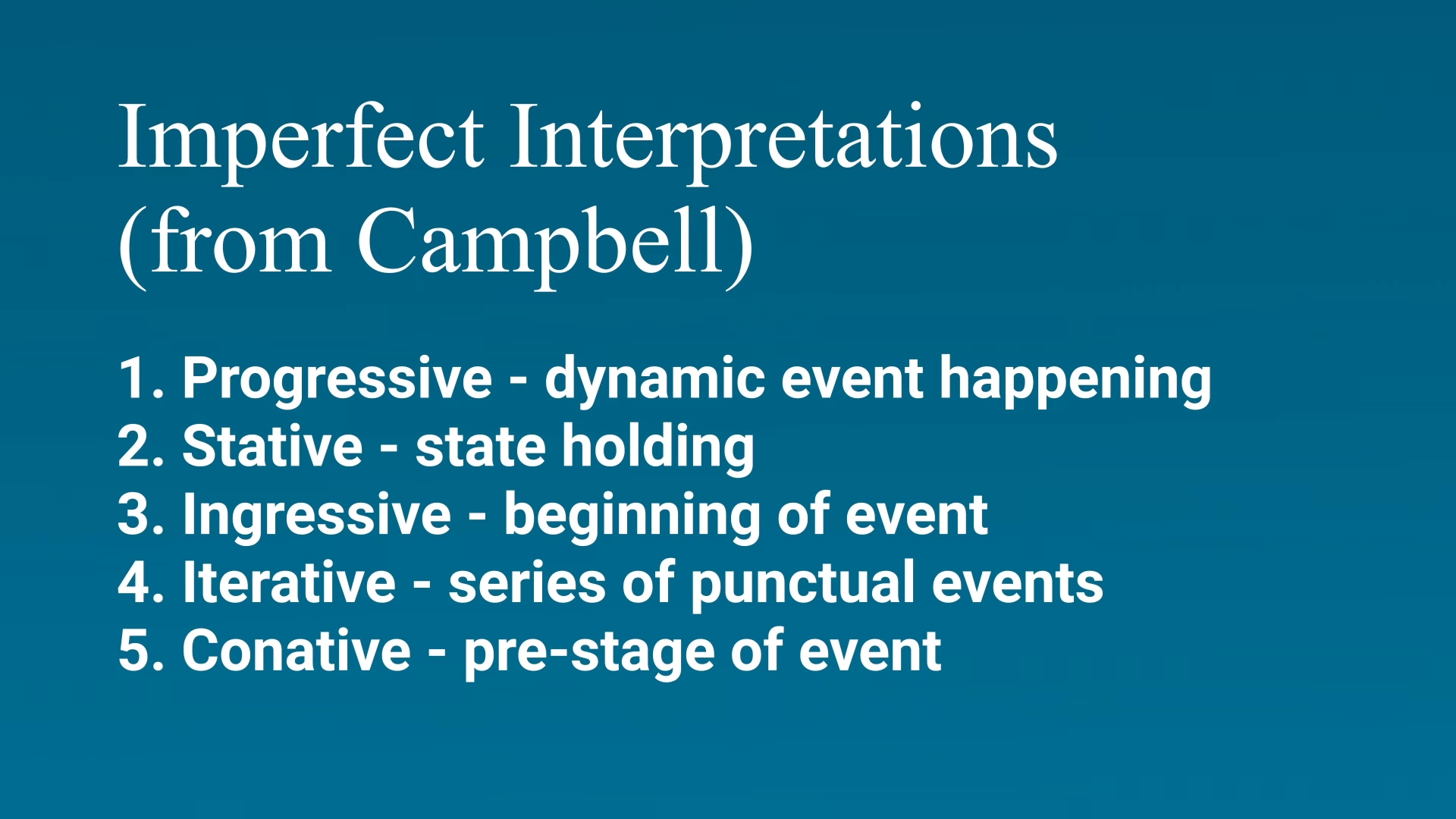

Likewise the interpretations given for the imperfect are all temporal, namely the progressive, stative, ingressive, iterative, and conative. We have already defined progressive, stative, and iterative temporally, and the only difference with the imperfect is that they are in the past. The ingressive refers to the initial temporal boundary of an event, and we have said that the conative refers to the pre-stage of an event.

We could do the same for all the other interpretations of the verb forms. My main point here is simple–if one side of Campbell’s equations, namely the interpretation, is necessarily a temporal value, then the other side must also be a temporal value. That’s what an equation is. It says that two distinct sets of values are equal even though they might be arranged differently. But we cannot jump categories. If the interpretation is always temporal, as Campbell’s interpretive categories suggest, then the things that lead to that interpretation must be temporal.

This brings us to our second main point here. Once we have defined a verb form, it is easy to read that meaning category back into the data.

I see this happen all the time with the imperfect form. People wrongly think that it is just like the English progressive, and they try to force an interpretation that would reflect that. However, as we explained in part 1, the imperfect is not equivalent to the English progressive, so that initial categorization is incorrect, and it would be wrong to read in the meaning of the English progressive into every Greek imperfect. Campbell does the same thing with the Greek perfect, which he calls an imperfective. He has wrongly called the perfect an imperfective, and he wrongly equates the imperfective with a progressive in English. He then claims that there is a “progressive” use of the perfect. Again, this is where the categories and definitions matter because they are being read into the data. Campbell lists the following verses as examples of the progressive perfect: Mark 7:37; John 17:6; Acts 21:28; 25:11; 1 Cor 7:15; 2 Tim 4:7; Jer 1:12. None of these should be understood as a progressive which Campbell defines (rightly) as a process or an action in progress. Let us briefly consider three of these examples. I do not cover them all for the sake of time, but after going through several, you can hopefully see how the others would be treated.

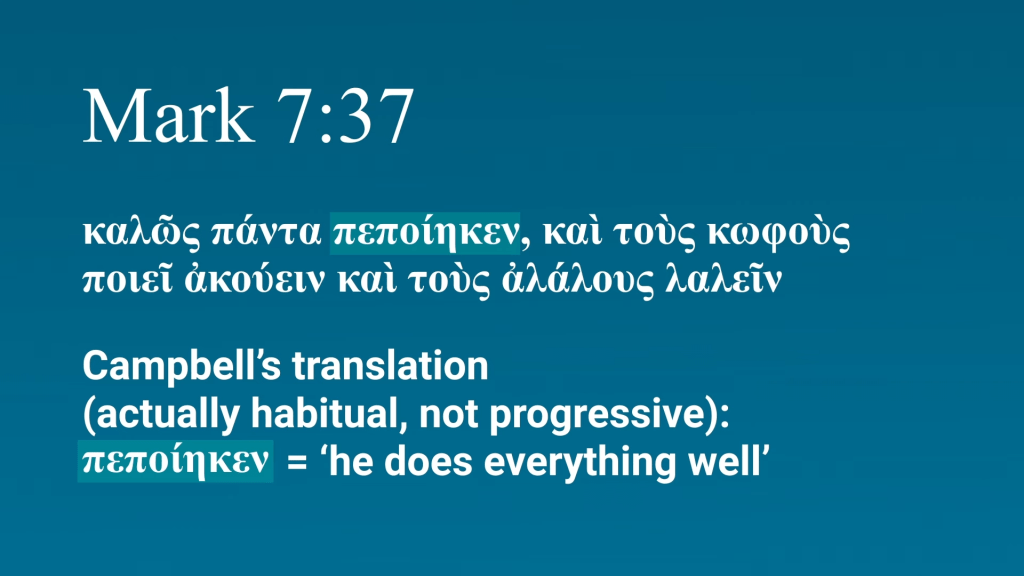

In Mark 7:37, a crowd exclaims a`bout Jesus that καλῶς πάντα πεποίηκεν, καὶ τοὺς κωφοὺς ποιεῖ ἀκούειν καὶ τοὺς ἀλάλους λαλεῖν. Campbell translates the initial perfect πεποίηκεν as ‘He does everything well’, which in English would really not be a progressive interpretation but a habitual.

Campbell does not explain why this would be a progressive, but it seems to be the following clause which gives the thing that Jesus does habitually, namely heal different kinds of people. However, the crowd is responding to a healing. It makes far more sense to interpret this perfect form as perfect aspect. There was a past event that was relevant to this present statement. The crowd claims that all the things Jesus has done, he has done well. They then make a general statement about what he does based on what he has done: he makes both the deaf hear and the mute speak. This general statement does not mean he is in the process of doing these things. It means he has the characteristic of doing these things. The perfect is a recognition that he has just done them.

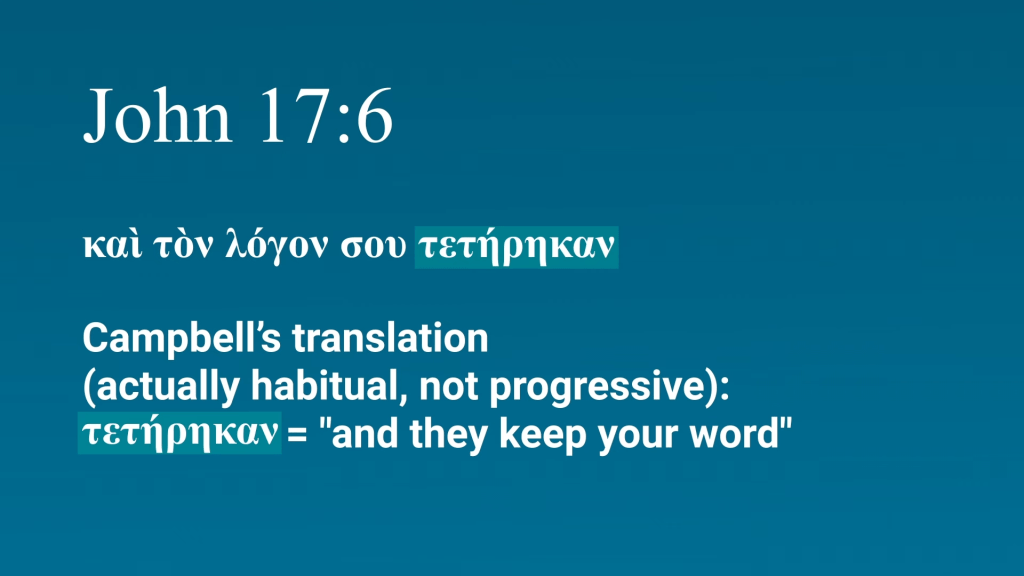

In John 17:6, we have the perfect τετήρηκαν in καὶ τὸν λόγον σου τετήρηκαν. Again, Campbell translates this with the simple present in English ‘and they keep your word.’ Just like Mark 7:37, this translation does not reflect a progressive interpretation, but a habitual in English. Jesus’s disciples, whom he is praying for, habitually keep his word, at least according to Campbell’s translation.

But again, the perfect interpretation, translated ‘they have kept your word’ is best here. Two verses later, Jesus speaks of his words which he gave to them and which they received, both clearly referring to past events. Moreover, it says that they believed that Jesus was sent by God. In context, then, Jesus is talking about things that disciples have done leading up to this moment. They are not currently keeping God’s word as Jesus is praying (which would be the progressive reading). They have kept his word in the past, and this is relevant now in Jesus’s prayer.

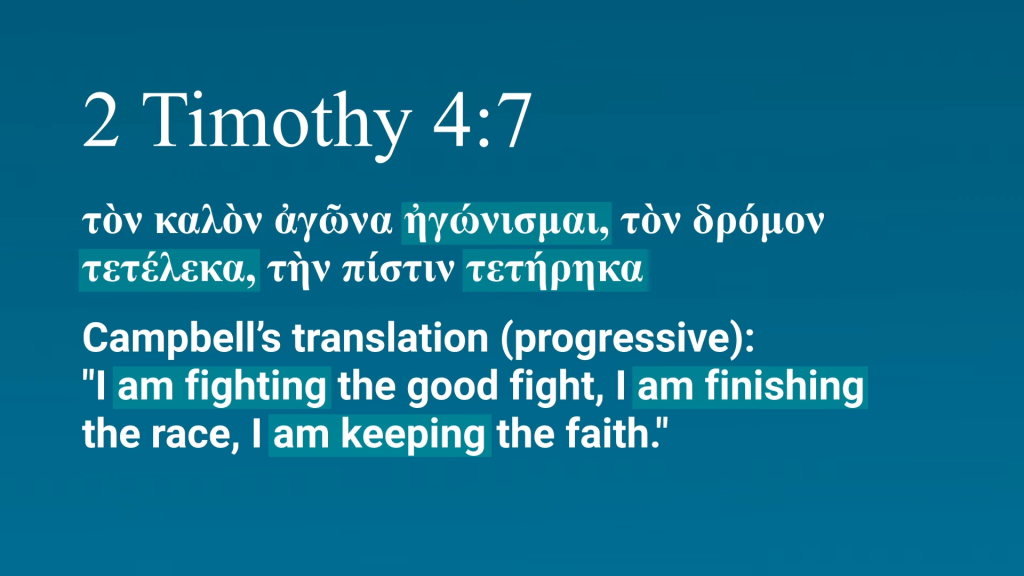

Finally, 2 Timothy 4:7 is one where Campbell actually does translate the perfect forms as progressives. The verse says, τὸν καλὸν ἀγῶνα ἠγώνισμαι, τὸν δρόμον τετέλεκα, τὴν πίστιν τετήρηκα, which he translates as ‘I am fighting the good fight, I am finishing the race, I am keeping the faith.’

Again, no explanation is given here, but the assumption is that Campbell interprets these clauses as a progressive because Paul has not actually fought the fight completely or finished the race or kept the faith for his whole life. He is still alive. However, this misunderstands Paul and does not adequately consider the meaning of the previous verse in which Paul says καὶ ὁ καιρὸς τῆς ἀναλύσεώς μου ἐφέστηκεν ‘and the moment of my departure has become imminent.’ The point is that Paul’s fight is effectively over. He thinks he is about to die. There is no more fight left. There is no more race to run. The faith has been kept throughout his life as a follower of the Messiah. The progressive interpretation would suggest that Paul still has more fighting left to do and his race is not effectively over, but he has said in the previous verse that he is already being poured out as a drink offering. The point of using the perfect forms here is to signal that Paul does indeed view his race as over. He has done everything he has been called to do. His time to die is now here. There is nothing left for him to do. The perfect gives you that meaning precisely. The progressive gives you the wrong interpretation. It says that Paul is still running the race and is not about to die. Once again, the traditional perfect offers a better explanation here.

My point in bringing up these examples is that it is easy for scholars (myself included) to read our definitions of the verbal forms into potentially ambiguous examples. Campbell calls the perfect form an imperfective. He equates the imperfective with the English progressive. He knows that the English progressive has a use where it refers to a dynamic event in progress, so logically, the perfect form should have this use as well under his system. This meaning is then read into contexts. This is where the meaning we ascribe to the verbal forms actually makes an interpretive difference. Either Paul is saying that he has finished the race, or he is saying that he is in the middle of the race, but he is not saying both. My claim is that Campbell has interpreted Paul wrongly here because of his theory about the perfect. I demonstrated at length in my review of the first part of Campbell’s book that the temporal definition of the perfect as referring to an event or state that precedes the reference time best accounts for the data. It also best accounts for these verses as well which Campbell says should be understood as progressives.

Our third and final point for chapters 7 to 9 is how to map Greek onto English, and we will use the historical present as our test case.

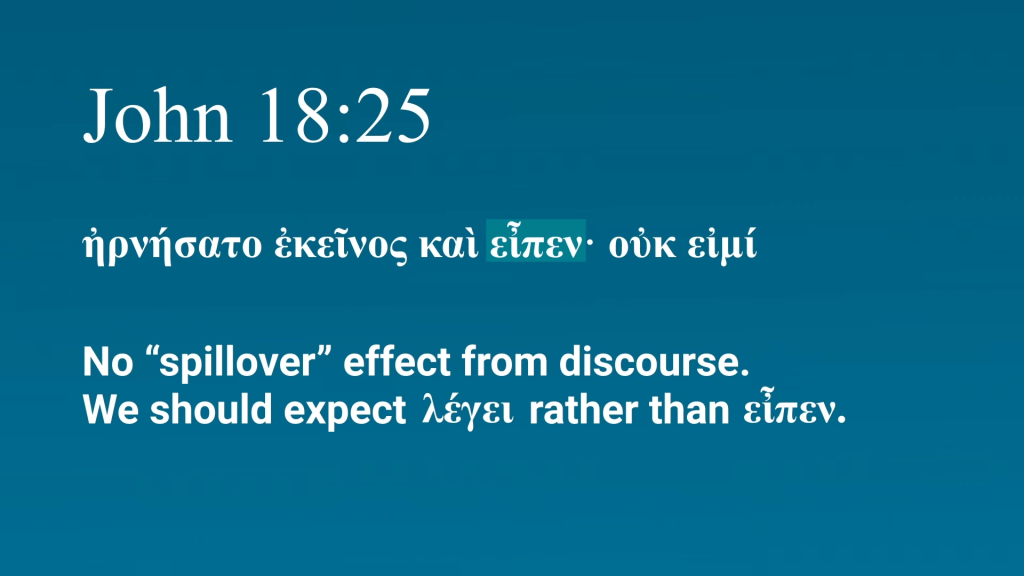

Campbell says that there are basically two different types of historical presents: “those that introduce discourse and those that employ lexemes of propulsion.” I suggest that these two categories, which we will refine, should receive two different explanations, and Campbell also gives two different explanations. For verbs of speaking, he says “historical presents that introduce discourse utilize the present tense-form because they are leading into a proximate-imperfective context (discourse). In such cases, the proximate-imperfective nature of discourse “spills over” to the verb that introduces it.” Of course, the biggest problem with this is when the aorist form εἶπεν is used with no “spill-over” effect. In other words, there are plenty of cases where discourse is introduced by an aorist form, so these would be left unexplained, or at least it is not clear when you would have a present form and when you should have an aorist. For example, John 18:25 says of Peter ἠρνήσατο ἐκεῖνος καὶ εἶπεν· οὐκ εἰμί ‘He denied it and said, ‘I am not.’ The aorist verb εἶπεν is immediately followed by discourse in this example, so if there was ever a context where we should expect spill-over, it would be here.

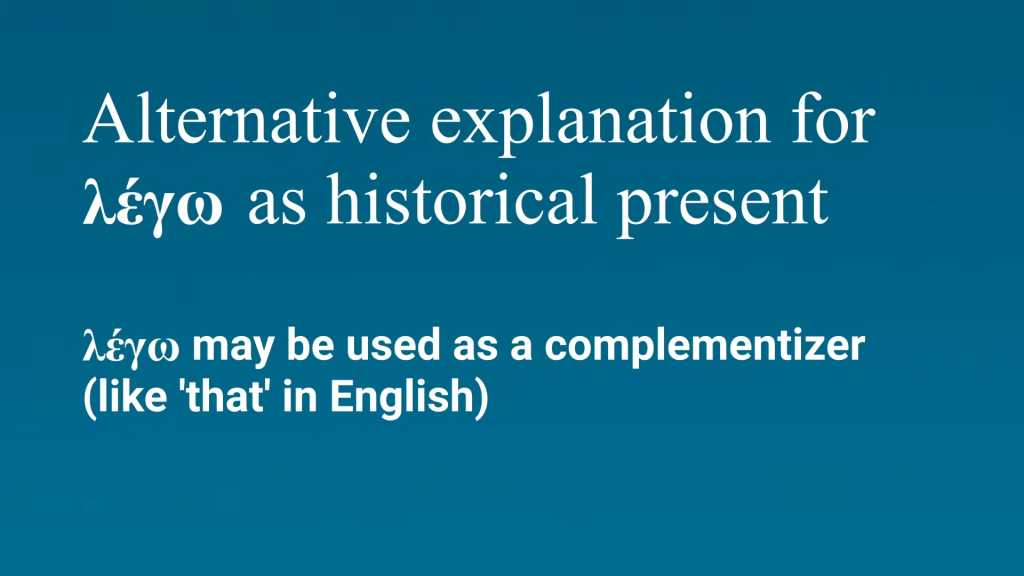

I suggest a different reason why the verb λέγω ‘say’ is used with the present tense form to introduce direct discourse. First, the fact that it is only λέγω that is consistently used like this and not other verbs of speaking, such as λαλέω, suggests that there is something going on with the verb λέγω and not the present tense form itself. This leads into my suggestion: λέγω may be used as essentially a complementizer to introduce a complement clause, similar to the word ‘that’.

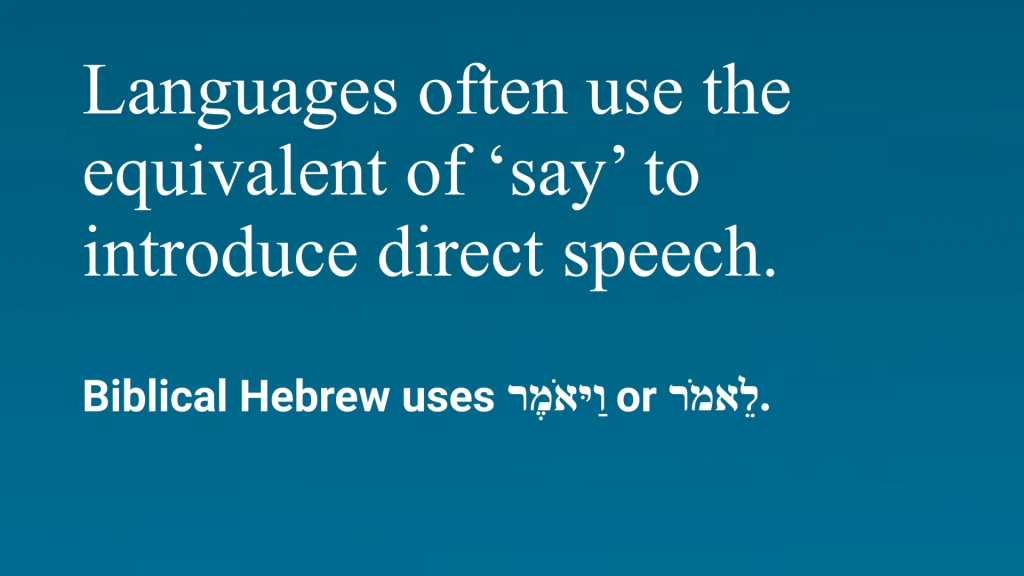

In a number of other languages, the equivalent to the verb ‘say’ comes to mean something very similar to a quotation marker. Biblical Hebrew is actually one such language where either וַיּאֹמֶר or לֵאמֹר can both introduce direct speech following another verb of speaking.

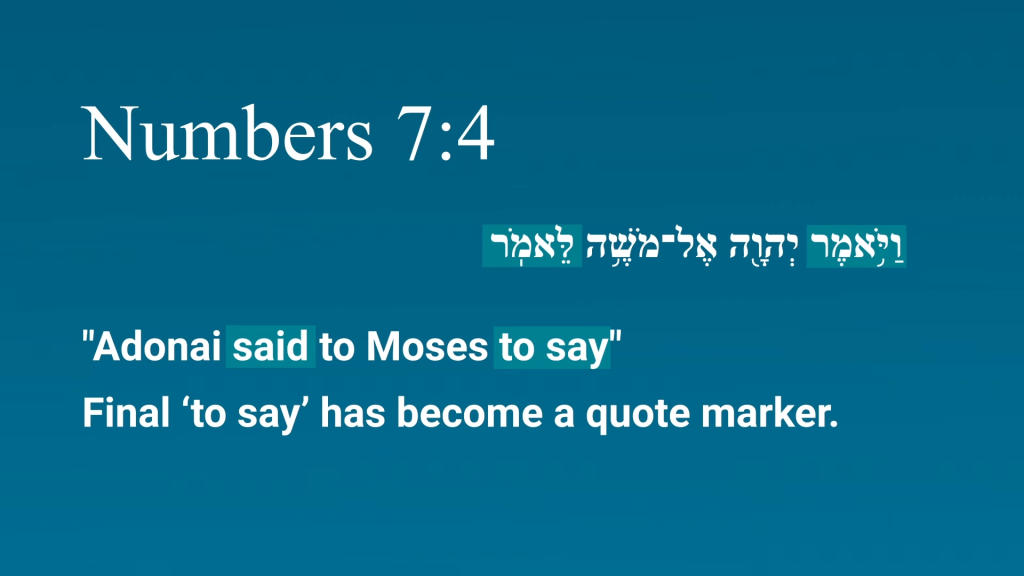

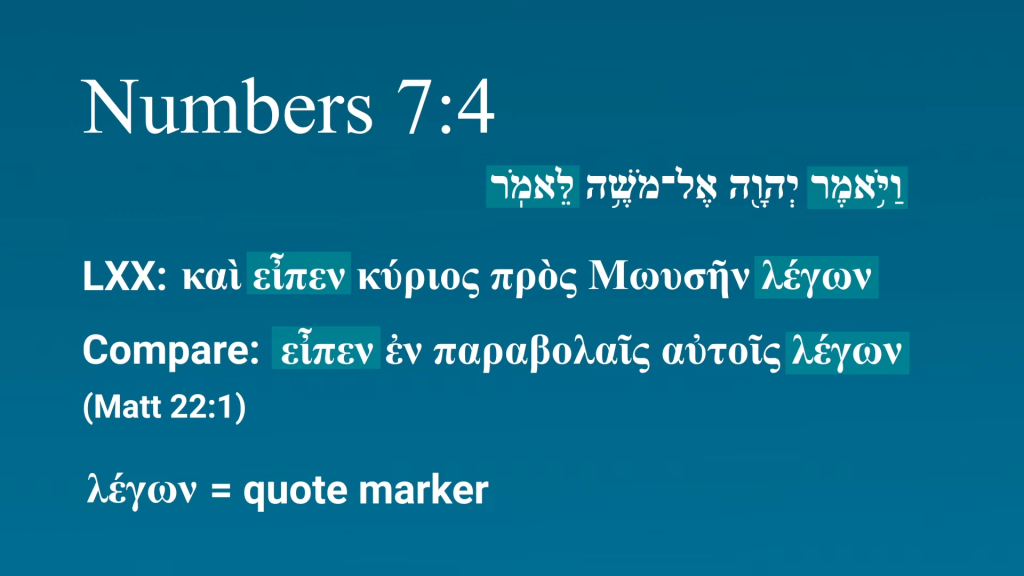

The way we know that the verb has become a quotation marker and has lost its original meaning is that the verb can follow itself. In Numbers 7:4, for example, we have וַיּאֹמֶר יְהוָה אֶל־מֹשֶׁה לֵּאמֹר where the initial verb ‘said’ precedes the infinitive ‘to say’. A translation of every single morpheme literally would be ‘Adonai said to Moses to say.’ The reason why this is not redundant is that the final ‘to say’ no longer means ‘to say’. It is just a quote marker.

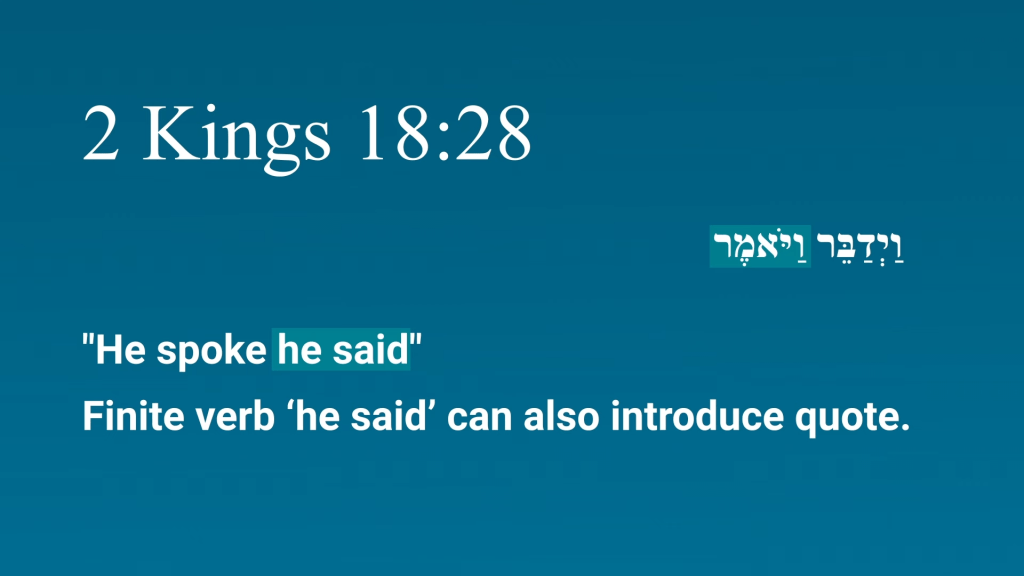

In Biblical Hebrew, the verb וַיּאֹמֶר can also have this function of introducing direct speech. An example like 2 Kings 18:28 says וַיְדַבֵּר וַיֹּאמֶר ‘he spoke, he said.’ Again, the ‘he said’ here is simply introducing the quote that follows.

When you look at the Septuagint of a verse like Numbers 7 :4, we have καὶ εἶπεν κύριος πρὸς Μωυσῆν λέγων where the participle λέγων is again redundant. This is essentially equivalent to what we have in Matthew 22:1 which says εἶπεν ἐν παραβολαῖς αὐτοῖς λέγων. The point here is that we see the New Testament authors using λέγων as equivalent to a quotation marker, just as we saw in Hebrew with לֵאמֹר and as we find in the LXX.

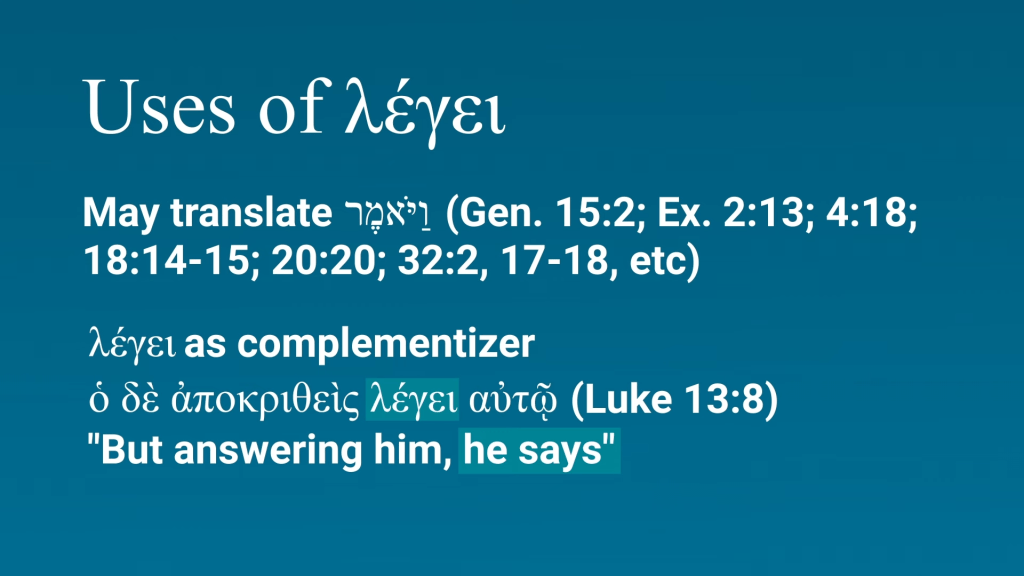

The parallels go deeper, however. The present form λέγει often translates the past tense form וַיּאֹמֶר in Hebrew, which we have already said can also be equivalent to a quotation marker. Indeed, λέγει is used in a very similar way in the New Testament in a verse like Luke 13:8 where it says ὁ δὲ ἀποκριθεὶς λέγει αὐτῷ ‘But answering him, he says.”

In English, we do not need the final ‘he says.’ We can just say ‘But he answered him’ followed by the quotation marks that introduce the quote. In both Greek and Hebrew, the verb ‘say’ is often used to introduce the quote. Crucially, however, the verb in such contexts is no longer functioning as a verb. It is not giving you the time when the event took place, but it is simply introducing a quote. In semantics, we would call this semantic bleaching. One meaning component of the original verb has been lost when it has taken on another function, namely to introduce direct speech. The point here is simple: the verb λέγω is not an argument against the present tense being a true present tense. That specific verb has lost its original tense meaning, but that does not mean that the present tense itself has changed its meaning.

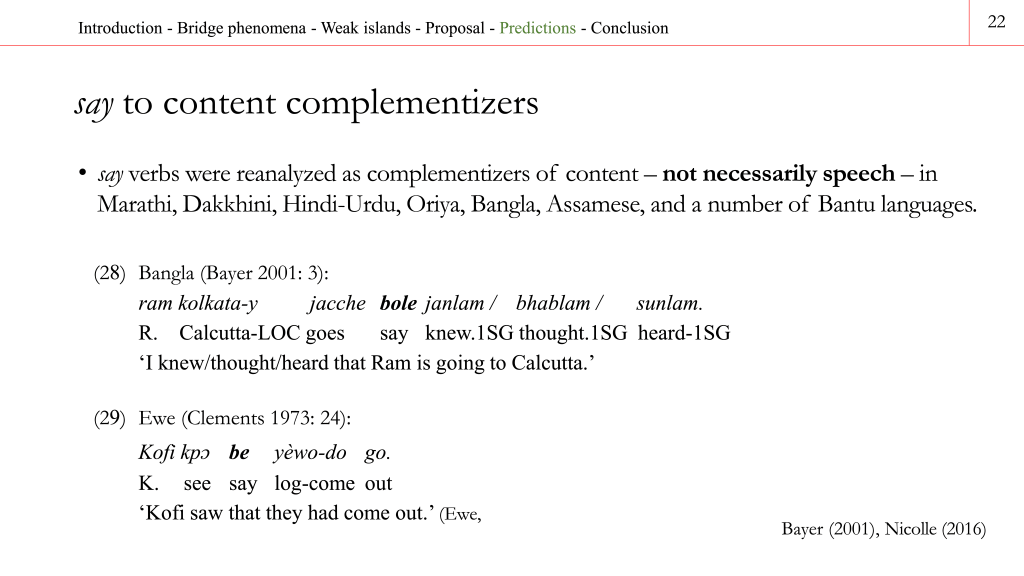

Let me clarify what I am saying and what I am not saying at this point. In both Greek and Hebrew, ‘say’ verbs are reanalyzed as complementizers. It could be the case that Hebrew is influencing the Greek of the New Testament authors at this point, but it need not. My friend Noa Bassel from Hebrew University has shown that say-verbs become complementizers in a number of unrelated languages, including Marathi, Dakkhini, Hindi-Urdu, Oriya, and others.

In other words, this is a known phenomenon across many languages, and there is a reason for it (you can check out her work for the reason). It should come as no surprise, then, that Biblical Greek and Hebrew do the same thing. Whether or not we have Hebrew influence here really does not matter. The data suggests that semantic bleaching for a certain verb is the best explanation, and the fact that this is found in a number of other unrelated languages confirms this.

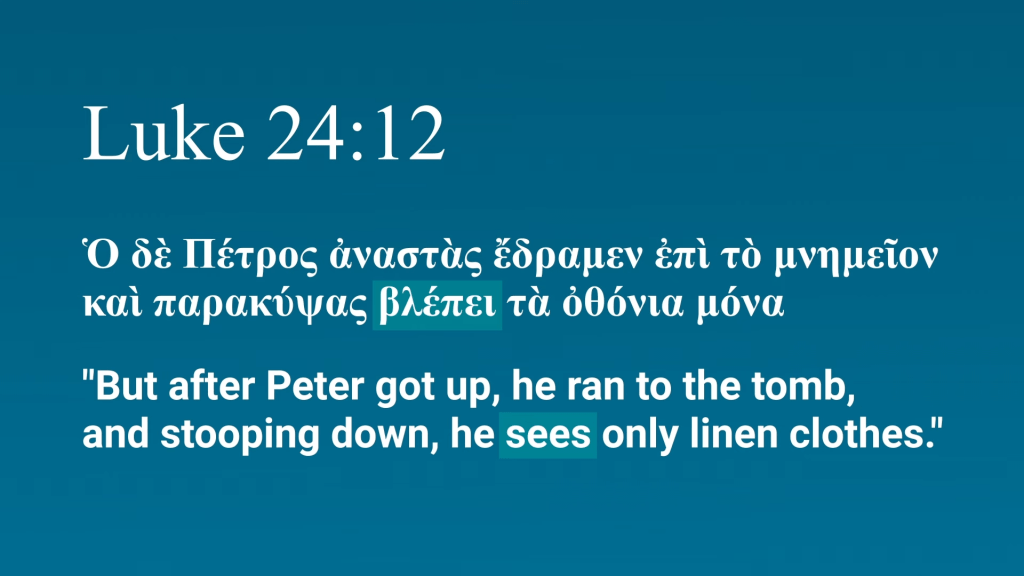

Campbell says that the other class of verbs where we have the historical present is with “verbs of propulsion.” This, I argue, is simply not correct. There are clear examples of historical present verbs that cannot fit into the category of “verbs of propulsion”, which Campbell defines as “verbs that convey transition–movement from one point to another.” One example is the verb βλέπει as found in Luke 24:12, which says Ὁ δὲ Πέτρος ἀναστὰς ἔδραμεν ἐπὶ τὸ μνημεῖον καὶ παρακύψας βλέπει τὰ ὀθόνια μόνα ‘But after Peter got up, he ran to the tomb, and stooping down, he sees only linen clothes.’

Because of examples like these, Campbell’s explanation of the historical present (which necessarily makes reference to a transition) cannot be correct. In my review of part 1, we suggested a different explanation for the historical present–the temporal anchor shifts to the time that is being talked about, namely the reference time. This means that the present tense has its normal meaning, since the temporal anchor and the reference time overlap. This temporal explanation also explains the meaning difference between a normal past tense form and the historical present. When a historical present is used, the speaker’s “now” moves to the time of the story itself. The narrator essentially brings the addressee with him or her back to the time when the event actually took place, and this shift in time is what gives the historical present its “vivid” nature. The addressee is now placed at the time of the event and is, in this sense, watching the events unfold. This is the reason why significant events are often placed in the historical present. Luke 24:12 is one such example. By bringing the reader back to the time when Peter sees only the clothes, Luke draws attention to this event in particular.

Campbell says that the historical present should normally be translated as a simple past, but I suggest that this is incorrect. We have the historical present in English as well, and we can just as easily use it to highlight certain events in the narrative. It is true that the verb λέγω should often receive a past tense translation or no translation at all, but this is because, as we have said, it is the verb λέγω that has a unique meaning and not the present tense. Hence, these are not true examples of historical presents. When we do have true historical presents, it is normally best to translate them as that–historical presents. This draws attention to the parts of the story that the author is drawing attention to.

In going into detail on a few points in this section, I hope I have shown that the details matter. The nuances in translation affect our interpretation, and our analyses of the verbal forms affect the nuances we see in translation.