Chapter 6

If you have made it with me this far in my review of Campbell’s book, I know you are serious about Greek grammar. This part will be similar in that we are going to discuss linguistic principles alongside Campbell’s analysis, but we are going to go deeper into a few passages in order to see how exegesis is affected by adopting Campbell’s position or that found within linguistics. So let’s dive in.

Chapter 6 begins with terminology, so I again briefly want to point out the differences between how Campbell uses the terms aktionsart and implicature and how linguists use them. This is not to beat a dead horse but to help clarify terms and meaning at the outset. As I tried to do in my evaluation of part 1 of Campbell’s book, I will try to evaluate Campbell using his own definitions of terms. Campbell opens part 2 by saying that “verbal aspect operates in cooperation with various lexemes to produce Aktionsart expression (also known as implicature).” For Campbell, then, “aktionsart” is the final interpretation of a verb in context, and if I am understanding him correctly, “implicature” would be a more general term to refer to any sort of interpretation in context, not just the interpretation of a verb.

I mentioned in part 1 that Campbell’s use of terms here is not super important in that we both have the same theoretical categories even if we use different terms for them, but it is worth clarifying how linguists would use the same terms because they do use these terms differently. In linguistics, aktionsart refers to the temporal structure of the verbal description. It is also sometimes called lexical aspect, whereas verbal forms like the present or perfect are called viewpoint/grammatical aspect markers.

The term “verbal aspect” (found in the title of the book and popular among New Testament scholars) is typically not used today in linguistics, and the reason is simple: the term “verbal aspect” could be referring to either aktionsart/lexical aspect or viewpoint/grammatical aspect.

I will not go through introductory textbooks, Chat-GPT, Wikipedia, and whatever other sources to prove that linguists define aktionsart in the way I am describing it, but I could. We will suffice ourselves with just one example.

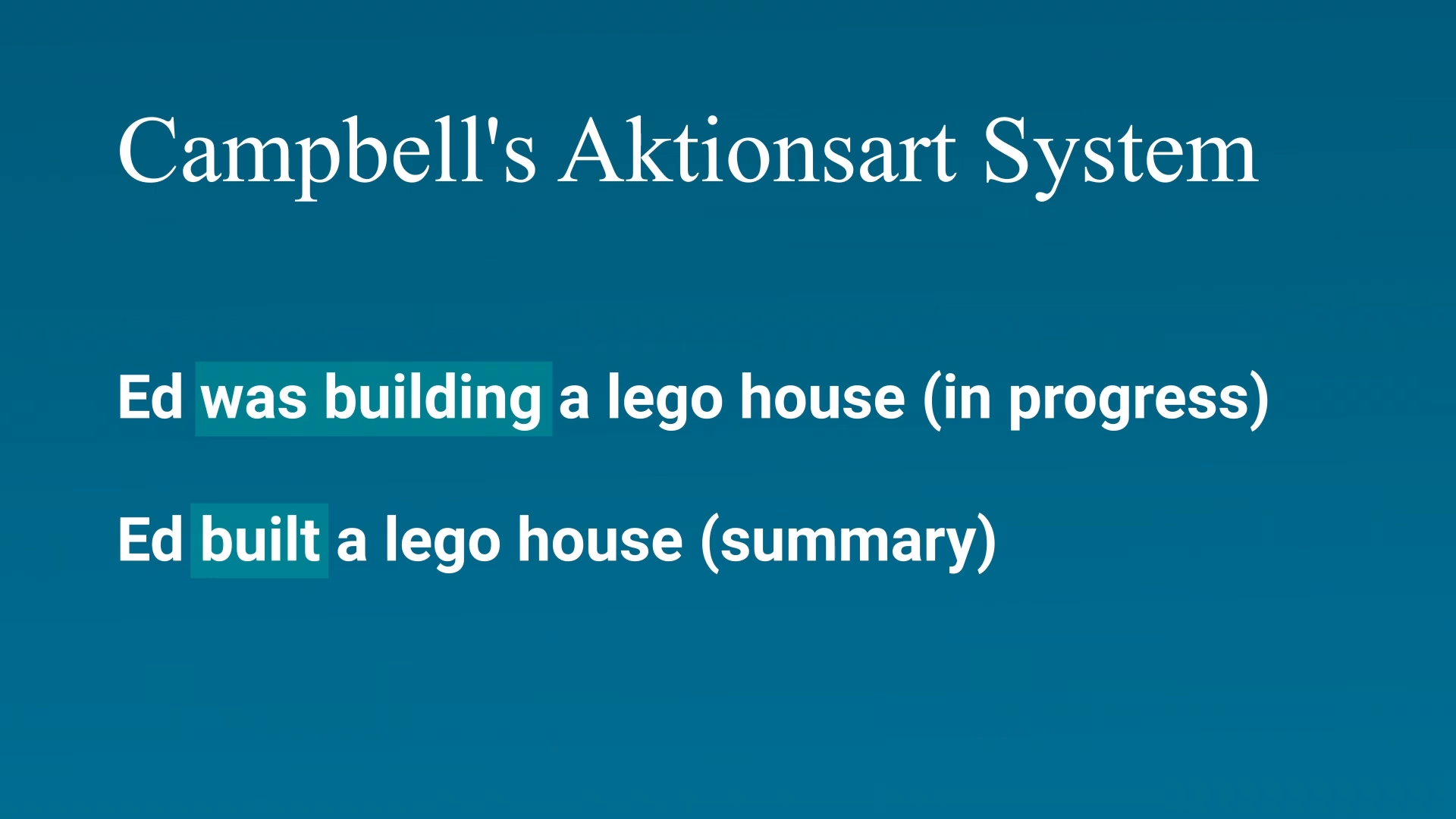

In Paul Kroeger’s semantics textbook, which can be accessed free online, he describes aktionsart as “the kinds of situations that speakers may want to describe.” Thus, aktionsart refers to the temporal nature of the event before that event description combines with any aspectual or tense markers. In Campbell’s definition, he makes aktionsart the interpretation of the clause after tense and aspect combine with the situation description. Again, Campbell’s system would have two different aktionsart values for ‘Ed was building a lego house’` and ‘Ed built a lego house.’ The former would be that the event is in progress, while the latter would be something like a summary view (again, using his terms).

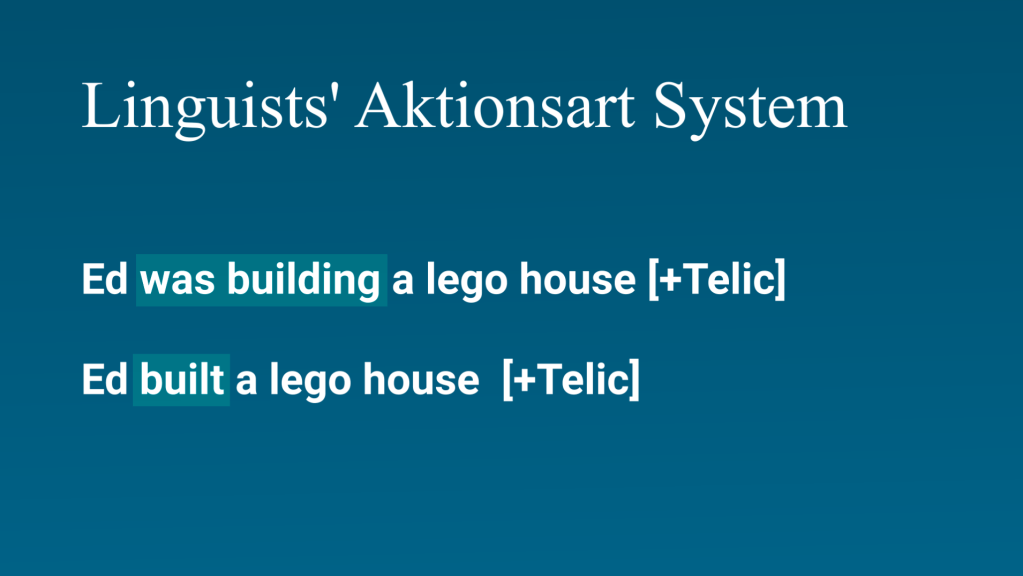

However, in linguistics we would say that these two sentences have identical aktionsart values. Both event descriptions refer to an event with a natural endpoint, that is, both are telic.

When explaining the actual data, I will use the terms “interpretation” or “use” to refer to what Campbell call’s aktionsart, and I will use “aktionsart” as it is used in linguistics.

When Kroeger discusses different situation types, he says that “we are interested in those distinctions which are linguistically relevant, so it is important to have linguistic evidence

to support the distinctions that we make.” What does he mean by distinctions that are “linguistically relevant?” Essentially, these are distinctions in meaning that are reflected in the grammar of the language, that is, they are grammatically significant. The issue is that if we compare any two verbs, there are all kinds of distinctions we can make between the two eventualities they refer to. For example, while ‘eat’ refers to ing esting something solid, ‘drink’ refers to ingesting a liquid. This is a distinction between the two eventualities that the verbs refer to, but is this linguistically relevant in any way?

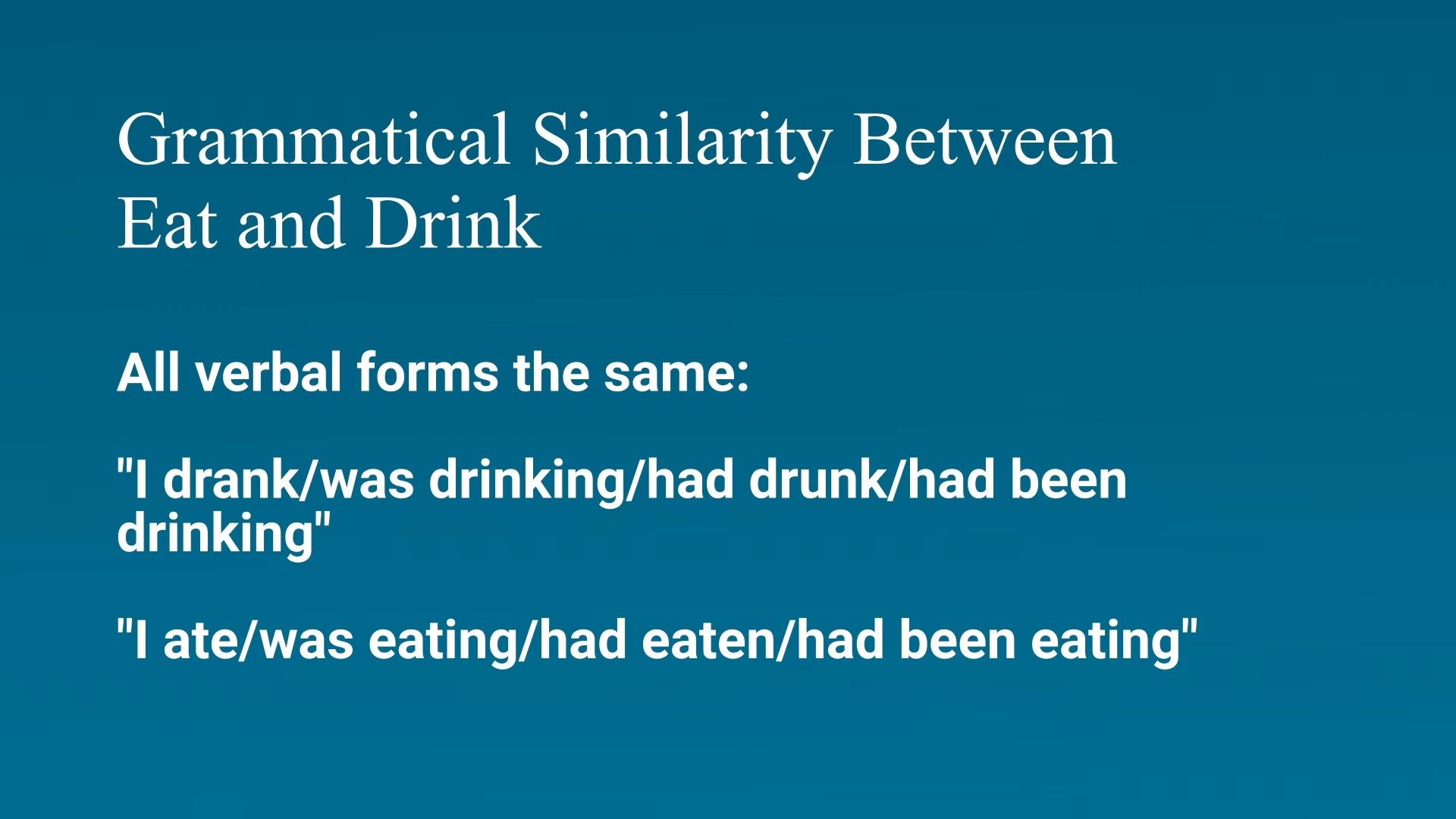

It is not. Both verbs can be found with all the different verbal forms in English, for example ‘I drank/was drinking/had drunk/had been drinking’ as well as ‘I ate/was eating/had eaten/had been eating.’

Likewise, both verbs allow for the object to be dropped as in ‘I am eating’ vs. ‘I am eating bread’ and ‘I am drinking’ vs. ‘I am drinking water.’

Clearly, ‘eat’ and ‘drink’ do not refer to the same event, but the distinction in meaning between the two is not linguistically relevant in the sense that both verbs interface with the grammar of English in the same way. Thus, the meaning distinction between ‘eat’ and ‘drink’ is not grammatically significant. The two verbs would fall into the same aktionsart category.

In chapter 6, Campbell again does not interact with the literature on aktionsart, or lexical aspect, and in failing to do so, he does not take into account the work that has already been done to develop categories that are linguistically relevant. Campbell’s system is idiosyncratic in a number of ways and does not use linguistic tests to distinguish between the different kinds of verbs. For example, he defines transitive not as taking a syntactic object in accusative case, but as an object being “affected or impacted somehow.” Again, I will not critique how he is using the term transitive, and I recognize that it is used differently in different circles within linguistics. It should be noted, though, that under his definition even a predicate like ‘hear the music’ is not regarded as transitive because the object is not affected or impacted. However, the deeper question is what does this distinction give us? Do we see transitive Greek verbs (in Campbell’s sense) interacting with the verbal system in a fundamentally different way than intransitive verbs? This was the motivation, for example, for stative vs. eventive verbs in English. Whereas an eventive verb is fine with the English progressive, such as ‘Olivia is drinking milk’, stative verbs are not, such as ‘Olivia is knowing math.’

Thus, the meaning distinction between ‘drink’ and ‘know’ affects how the verbs are used within the grammar of English. This tells us something about the meaning of the English progressive as well as states like ‘know.’ For each of the meaning distinctions Campbell cites, we would want to see similar such grammatical consequences. Otherwise, we could multiply meaning distinctions endlessly, and they would not help us to understand the verbal forms.

Besides the issue of what the categories are, there is also the issue of the imprecision with which the categories are defined and how that affects the categorization of verbs. To illustrate, the verb ἅπτομαι ‘touch’ is labeled as transitive, but something that is merely touched is not really “affected or impacted.” Again, the trouble is that without a more precise definition of what it means to be “affected or impacted”, it is hard to know how to categorize the individual verbs. I am not trying to be nit-picky here. Even of the small set of verbs Campbell treats, there are several which I would personally categorize differently based on Campbell’s short description, such as εὑρίσκω and ζητέω, where again Campbell labels them “transitive” though there is nothing that is affected or impacted. Because of this imprecision, there are verbs which Campbell himself labels as “Transitive/Intransitive?” like βλέπω, ἀκούω, and ἀγαπάω.

Let me summarize the two fundamental issues with chapter 6: we need to develop categories that affect the interpretation of the clause when combining with certain verb forms, and we need to be precise about those categories in order to know how to do the actual categorizing.

To illustrate how this is done within linguistics, we can compare and contrast Campbell’s description of what it means for a verb to be punctiliar with that of linguists. Campbell subsumes punctiliar under transitive verbs, which means that he is defining it as only applying to verbs with an affected argument. He says, “If a lexeme is transitive, it may also be punctiliar. A punctiliar action is performed upon an object and is instantaneous in nature. It is a once-occurring immediate type of action.” There are two components to this definition. One is that the action is performed on an object, and the other is temporal, namely that there is no duration. We have already suggested that the former is not a good feature for analyzing the temporal structure of verbs because whether or not an object is affected is not relevant to the meaning of the aspectual forms. It is not as if the class of transitive verbs, in Campbell’s sense, are only found with the aorist or get a special interpretation in the present. However, punctiliar, or instantaneous, events do get a special interpretation in many languages. Consider the following contrast in English:

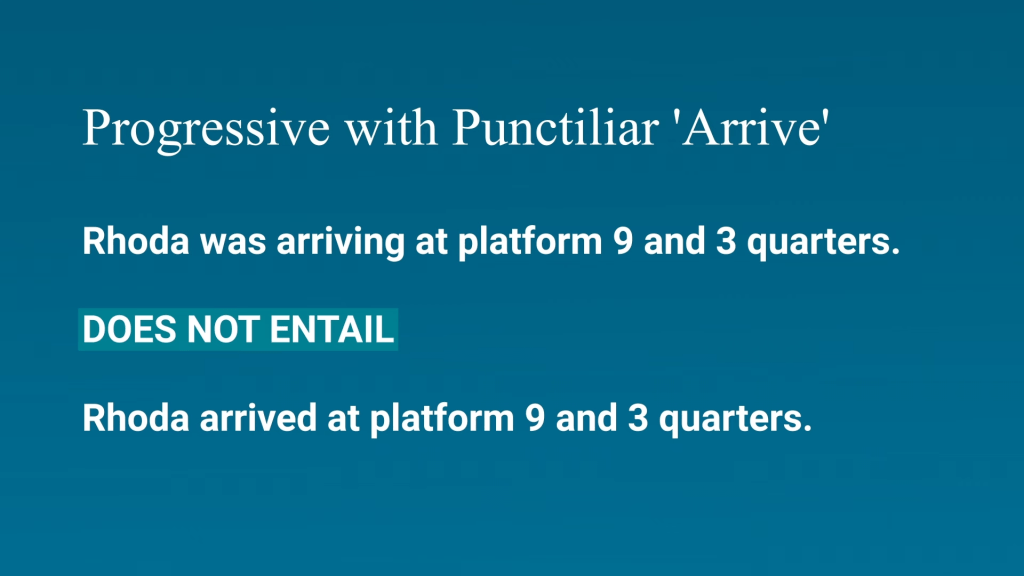

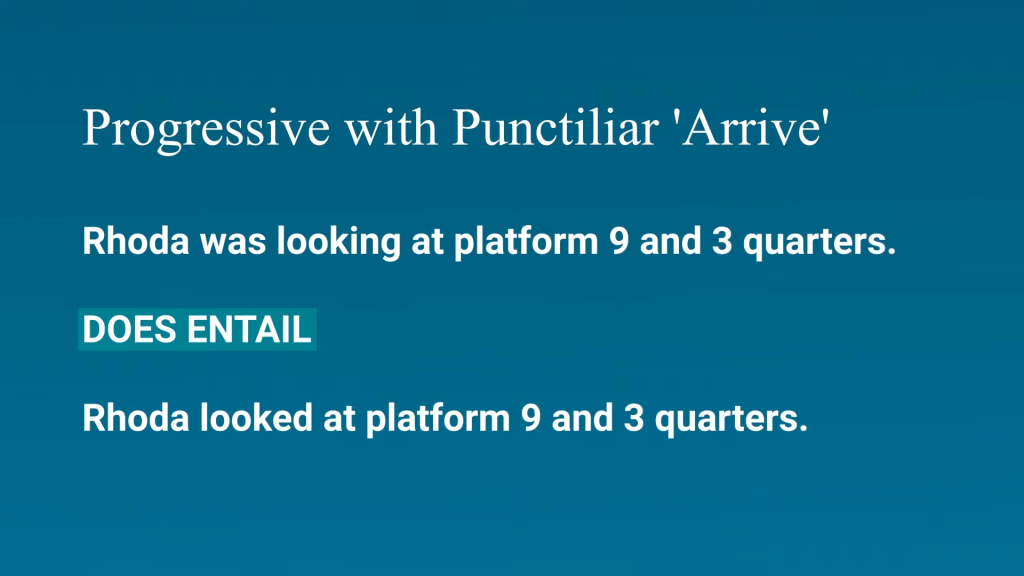

“Rhoda is arriving at platform 9 and 3 quarters.” vs. “Rhoda is looking at platform 9 and 3 quarters.”

Crucially, these two sentences differ in what they entail, which is another way of saying they have different interpretations. When the progressive form combines with “arrive”, it does not entail that the event actually took place. We cannot conclude that “Rhoda arrived at platform 9 and 3 quarters.” This is seen by the fact that we can cancel the sentence with something like “Rhoda was arriving at platform 9 and 3 quarters when she was suddenly attacked by a hippogriff. She never made it to the platform.”

In contrast, when we say “Rhoda was looking at platform 9 and 3 quarters,” we can conclude that Rhoda did indeed look at the platform. It is a contradiction to say “Rhoda was looking at platform 9 and 3 quarters, but she never saw it.” Because we cannot cancel this inference, it is what we would call an entailment.

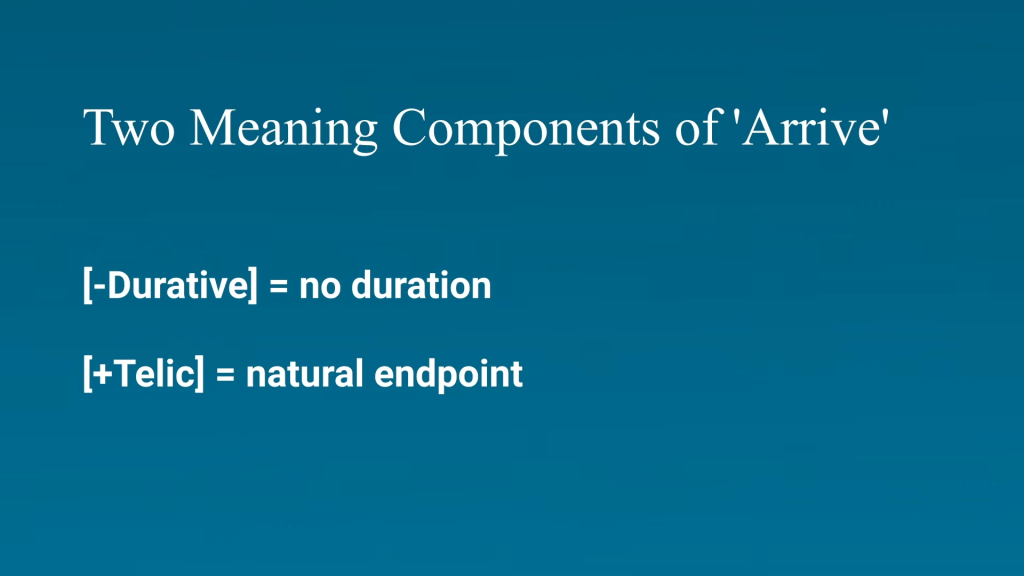

There are two grammatically significant meaning components to ‘arrive’ that make it differ from ‘look’. It does not have any duration, and it is telic, that is, it has a natural endpoint.

Once Rhoda reaches platform 9 and 3 quarters, the event of her arriving at the platform is over. Crucially, the prediction with this analysis is that all verbs with these features should behave in this way with the progressive. This is what makes such an analysis powerful and helpful in exegesis. We can begin to predict the interpretation of the sentence by noticing features of the predicate and how verbs with such features interact with verbal forms. This prediction is borne out with similar verbs like ‘reach.’ To say ‘Rhoda was reaching the summit of mount doom’ does not entail that she reached the summit. She may have decided to turn back just before actually reaching the summit. The linguistics literature is replete with similar examples with similar verbs and extensive discussions on what is going on semantically.

Structuring Events by Susan Rothstein

Structuring Events by Susan RothsteinYou can check out Susan Rothstein’s chapter on progressive achievements in her book “Structuring Events” for an extensive discussion on what is going on semantically.

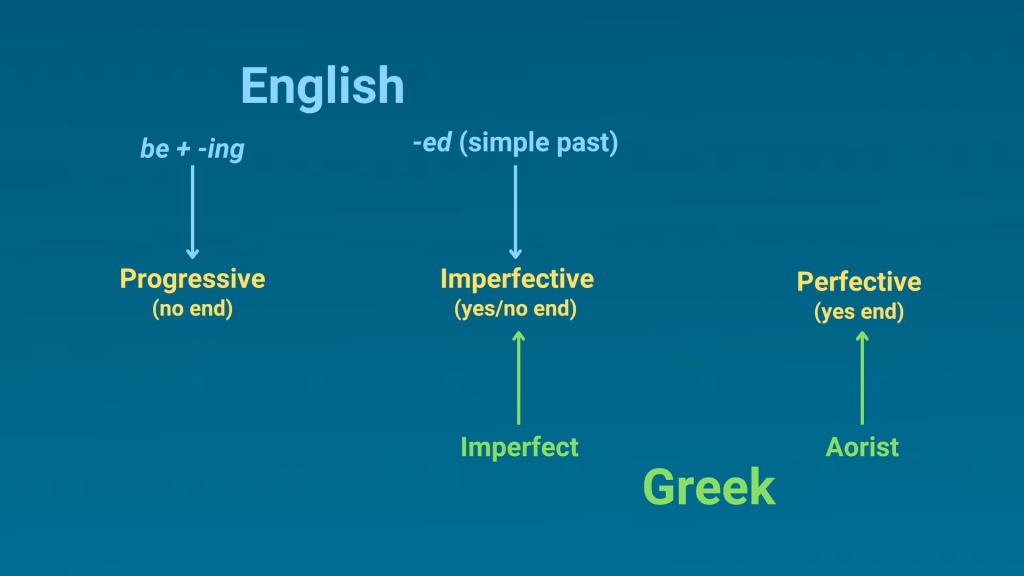

This data is not just relevant for the English progressive. It also helps us understand Greek. In my review of part 1 of Campbell’s book, I said that the Greek imperfective is not the same as the English progressive. Whereas the English progressive must refer to only part of an event, the Greek imperfective forms (the present and the imperfect) can refer to either part of an event or the entire event, particularly when that event has no duration.

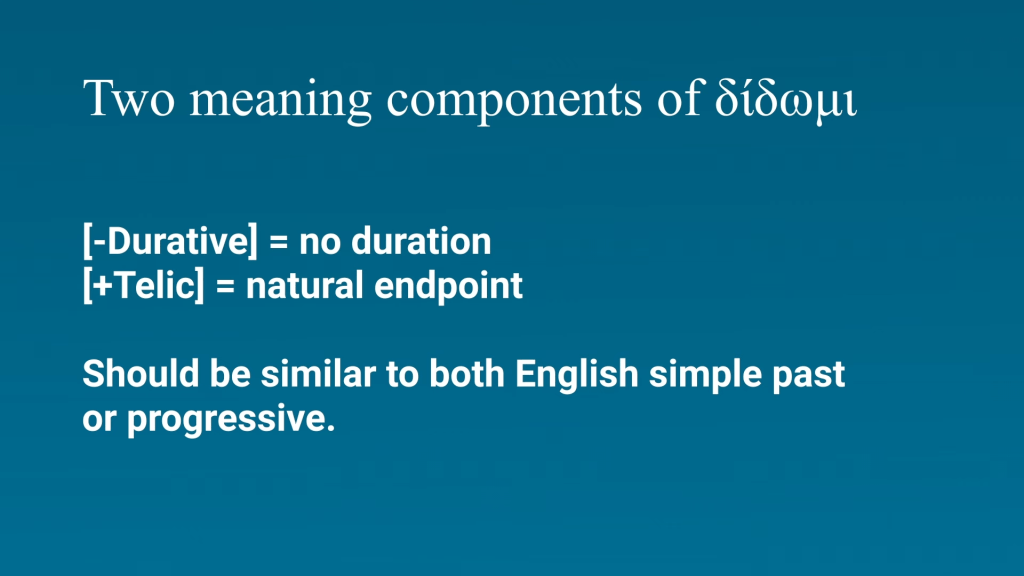

With the English progressive, a sentence like ‘Rhoda was arriving’ cannot refer to Rhoda having actually arrived somewhere. Because the Greek imperfective only overlaps partially with the English progressive, we should expect this reading with telic verbs without duration, but we should also expect a reading that is essentially equivalent to the aorist. Again, this prediction is borne out in a verb like δίδωμι ‘give’. In this verb, there is necessarily a transfer of possession, and when this takes place, the event is over. Hence, it is telic. There is also no real duration. Transfers happen when one thing moves from being possessed by one individual to being possessed by another individual. This happens instantaneously when something is actually exchanged.

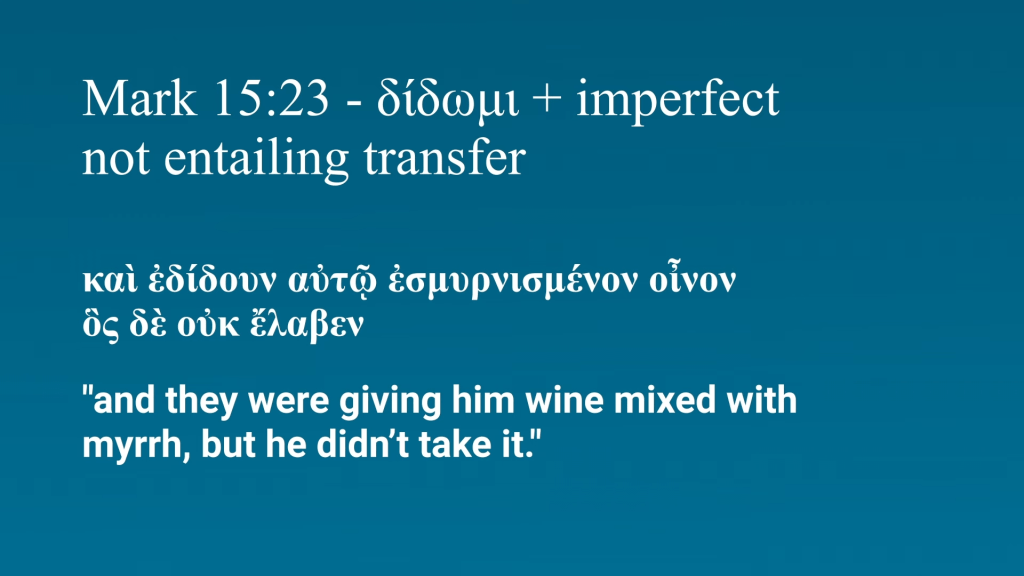

We see an example similar to the English progressive in Mark 15:23 where we read καὶ ἐδίδουν αὐτῷ ἐσμυρνισμένον οἶνον ‘and they were giving him wine mixed with myrrh.’ The next line says ὃς δὲ οὐκ ἔλαβεν ‘but he didn’t take it.’

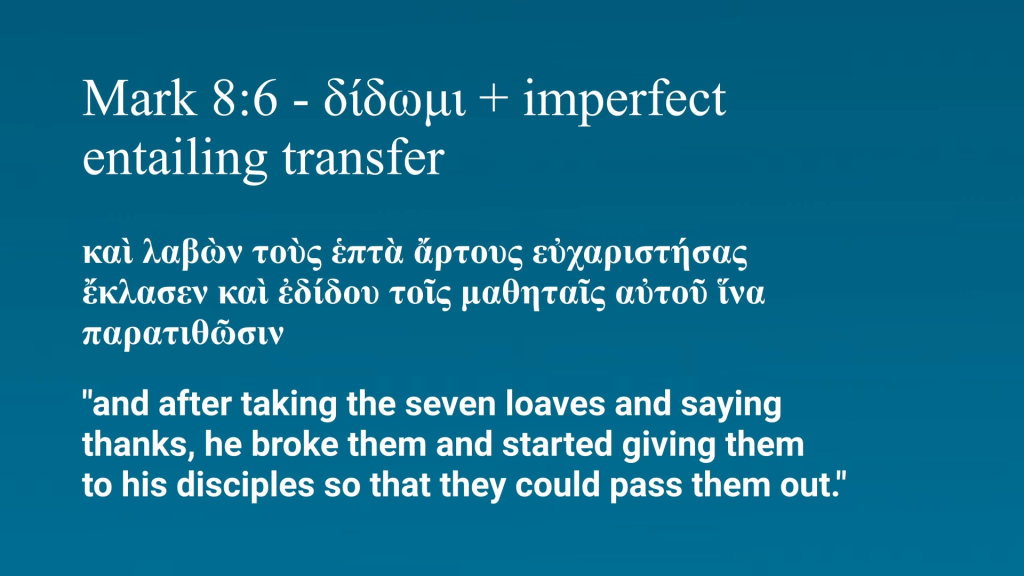

In other words, the transfer of possession never took place. In this example, the aorist form of the sentence is not entailed. We cannot conclude ἔδωκαν αὐτῷ οἶνον ‘they gave him wine.’ The end of the event is never reached. In contrast, we have the same verb earlier in Mark 8:6 where it is used in the description of the feeding of the four thousand. It says καὶ λαβὼν τοὺς ἑπτὰ ἄρτους εὐχαριστήσας ἔκλασεν καὶ ἐδίδου τοῖς μαθηταῖς αὐτοῦ ἵνα παρατιθῶσιν ‘and after taking the seven loaves and saying thanks, he broke them and started giving them to his disciples so that they could pass them out.’ Notice, this sentence does entail that the event of giving took place, even if it only refers to the beginning of the event and not the end, as my translation suggests. We can truthfully say ἔδωκεν ὁ Ἰησοῦς ἄρτους ‘Jesus gave loaves’. Thus, this reading entails that Jesus did indeed engage in the giving event. Given the nature of the verb δίδωμι and the semantics we have given to the imperfective, this ambiguity is predicted, and it is reflected in the data.

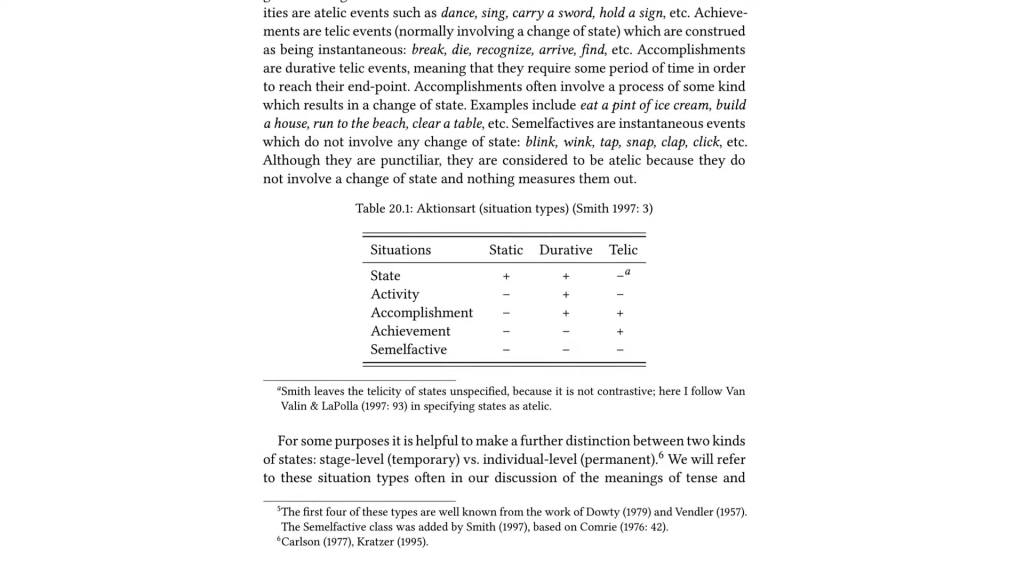

Coming back to Campbell, we can see how his categories for verbs do not always help us to determine the meaning of a verbal form in context. We need the category of punctiliar, but we do not want to subsume it under transitive, whether that is Campbell’s definition of transitive or the more standard syntactic one of taking an argument in accusative case. Campbell’s feature [+/-Transitive] does not help us to interpret verbs. The features developed in linguistics, specifically [+/-Durative], [+/-Telic], and [+/-Dynamic] do help us to interpret the verbal forms. As with other things we have discussed, these features have been nuanced, but they go back to the philosopher Zeno Vendler’s categorization of events in 1957, and they are still widely used today, especially in introductory works. The chart found in Paul Kroeger’s book serves as an example, and more discussion can be found there. Campbell essentially has the durative feature (which is [+/-Punctiliar]) as well as the dynamic feature (which is [+/-Dynamic]), but subsuming punctiliar under transitive and stative/dynamic under intransitive obscures the issues and leads to the wrong analysis. Lacking the feature [+/-Telicity] is also a large omission, as this feature has arguably received the most attention in the literature and is an essential part of any analysis of lexical aspect.