Returning to Campbell, he gives 6 examples of the perfect in this chapter. John 1:26 we have already mentioned, and it would fall under the present stative interpretation. It is unique in that the state is the only thing referred to, and the prior event is not obvious. However, this reading only obtains in a limited set of verbs, the most common being οἶδα ‘know’. This verb is actually from the root ειδ ‘see’. One can see how this kind of root developed the present stative interpretation. After you have seen something, you know it. As linguist Paul Kiparsky discusses, verbs that fall into this category are consistent across languages, and they usually refer to a state in which a past action can be inferred. Campbell also cites Luke 20:21 which also falls into this category.

Revelation 8:5 is an example of what looks more like a perfective interpretation than what we have described as a perfect. It says καὶ εἴληφεν ὁ ἄγγελος τὸν λιβανωτὸν καὶ ἐγέμισεν αὐτὸν ‘And the angel took the censer and filled it.’ The perfect εἴληφεν is immediately followed by the aorist ἐγέμισεν, and the two seem to be interpreted identically. In later Greek, the perfect will become the standard form for this kind of use, so it seems that we see the beginnings of that trend happening here. The Greek perfect is actually very similar to the Biblical Hebrew Qatal form in this respect. The details of how to account for this use get a little complicated, so instead of boring you with the analy sis, you can just check out my article on the Biblical Hebrew Qatal form. I’d also recommend Ashwini Deo and Cleo Condoravdi’s treatment of the Sanskrit -ta form which also has a similar range of meaning.

John 7:22 is another example, which says διὰ τοῦτο Μωϋσῆς δέδωκεν ὑμῖν τὴν περιτομήν ‘On account of this, Moses has given you circumcision.’ This is probably a result perfect, though it could also be existential. The idea is that the people now possess the practice of circumcision since Moses gave it to them. Thus, they are in a new state, namely of possessing circumcision, on account of the verb. Under the existential perfect reading, it would mean that a past action occurred prior to the time being talked about, namely the present. The next example is John 12:23, which says ἐλήλυθεν ἡ ὥρα ‘the hour has come.’ In this example, the verb ἐλήλυθεν ‘has come’ refers to an event with a consequent state, namely a change of location or time. Thus, this is a result state perfect. The hour has come and is now here in Jesus’s present moment.

Finally, Campbell cites John 5:33 which says ὑμεῖς ἀπεστάλκατε πρὸς Ἰωάννην, καὶ μεμαρτύρηκεν τῇ ἀληθείᾳ· ‘You have sent to John and he has borne witness to the truth.’ Both of these are best taken as existential perfects. Prior to the present time we are discussing, Jesus’s addressees sent people to John and John has already told them the truth. The perfect is used because the present time is what is relevant in the discourse. John already told them the truth. Now in this present time, they should know better.

These are the examples Campbell cites against the other theories, the examples that the other theories supposedly cannot account for. I am not going to say anything against the other theories, but the standard temporal theory of the perfect in linguistics accounts for all of them. Campbell calls the perfect an imperfective essentially because many of the uses parallel the present form. He says, “An overlooked fact in this debate is that the perfect indicative parallels the present indicative in its usage far more than it seems to do with the aorist.” Campbell concludes from this that they share the same aspect, which, as we have said, he has described as something like a more “detailed” viewpoint. The same issues with his description of the present form as imperfective would then apply to the perfect. It is very difficult to know what he means by “detailed”. Moreover, Campbell is then left with three imperfective forms, none of which are distinguished based on tense. Because of this, he suggests that the perfect has “heightened proximity” in comparison to the present. So whereas the imperfect is remote and imperfective and the present is proximate and imperfective, the perfect is very proximate and imperfective. We will come to the idea that verbal forms can express spatial notions shortly.

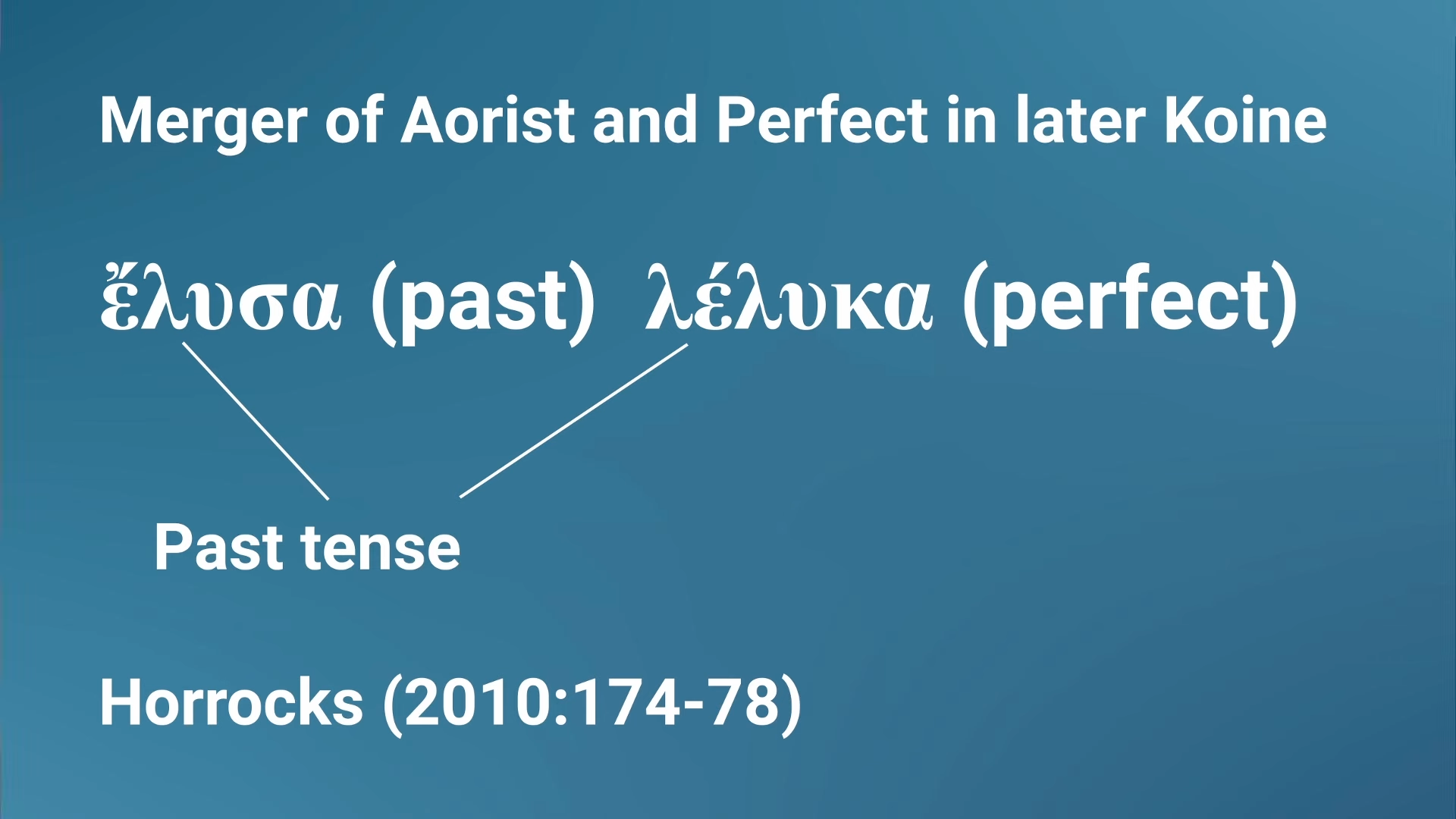

Campbell has not been followed by many in his analysis of the perfect form, so again, I do not want to belabor the point. However, it is worth pointing out that making the perfect form identical to the present form in aspect would be against what we see in the morphology. What do I mean by this? Both the present and imperfect forms have the same stem, and this indicates their aspect. The verb λύω is λύω and ἔλυον with the main differences being the initial ε (traditionally marking the past tense, which I would also agree with) and the shortened person and number endings. The perfect form is λέλυκα. If the initial reduplication is giving us Campbell’s notion of “heightened proximity,” then the final κα would give us the aspect. Since the aspect is the same as the imperfective forms, we would expect the same stem, so we would expect something like the form λέλυον.