We now come to chapter 4, which is on imperfective aspect. Since perfective and imperfective aspect are described as opposites, some of the same concerns with Campbell’s definition of perfective apply also to imperfective. He says that with the imperfective aspect “an action is presented as though unfolding before the eyes.” He goes on to use an example from the progressive form in English to illustrate when he says, “This is easy to appreciate in English ‘he is walking down the street’ is clearly cast before us as though we are watching it happen.” Again, it is difficult to know what he means by this because it is clearly metaphorical. We need not be watching someone walk down the street to utter the sentence, so what does it mean to be metaphorically “watching it happen?”

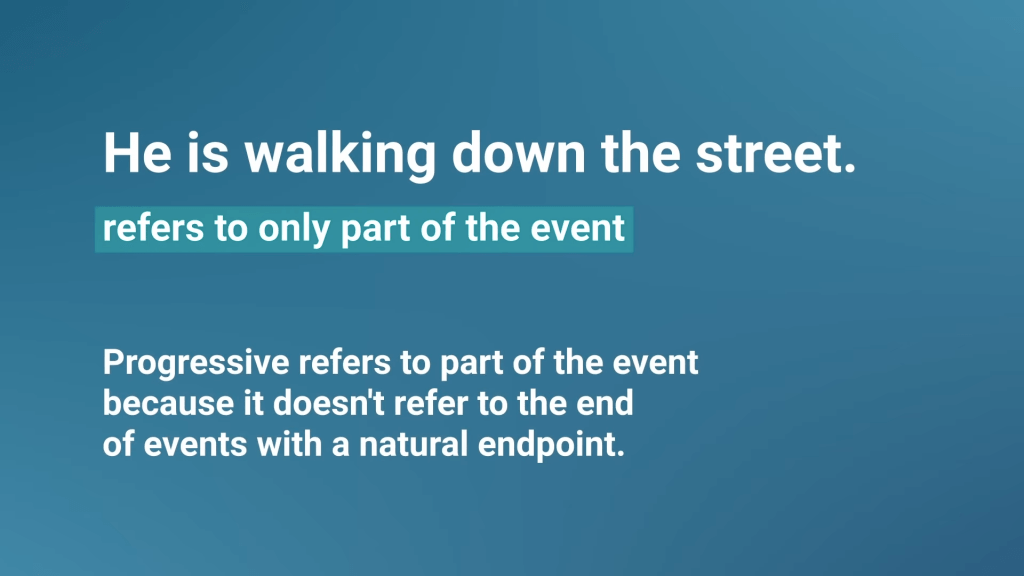

Focusing on English first, linguists would not call the English ‘be + -ing’ form an imperfective. They call it a progressive. Semanticists like Fred Landman have essentially defined the progressive as referring to a non-maximal stage of an event, though the progressive has received various treatments. However, all consider it to be temporal and to essentially disallow reference to the end of an event. So a sentence like ‘he is walking down the street’ does not cast the event before our eyes. It is simply refers to part of the entire walking down the street event. The way we know the progressive refers to only part of an event (and not the event’s endpoint) is how it combines with events that have a natural endpoint.

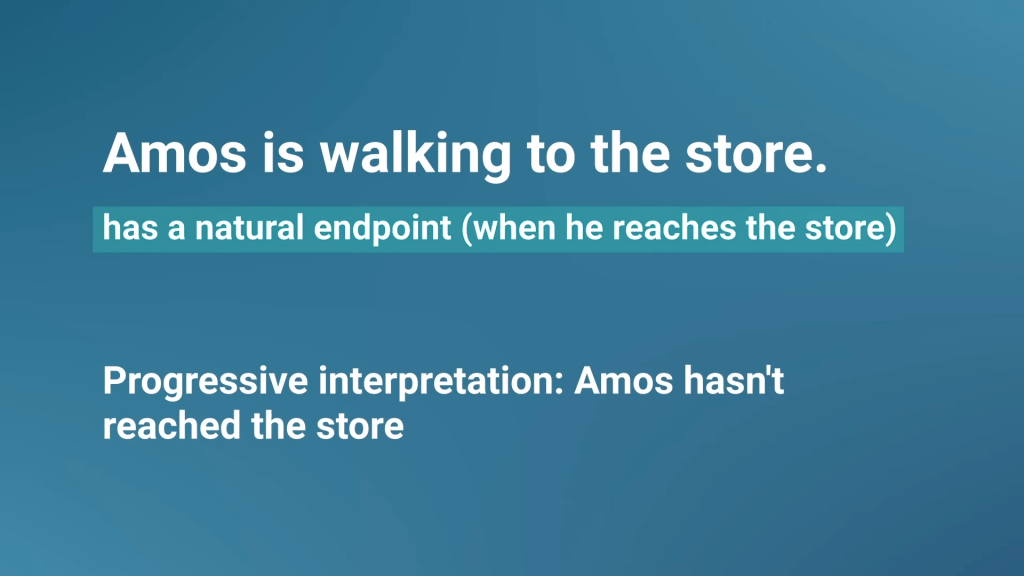

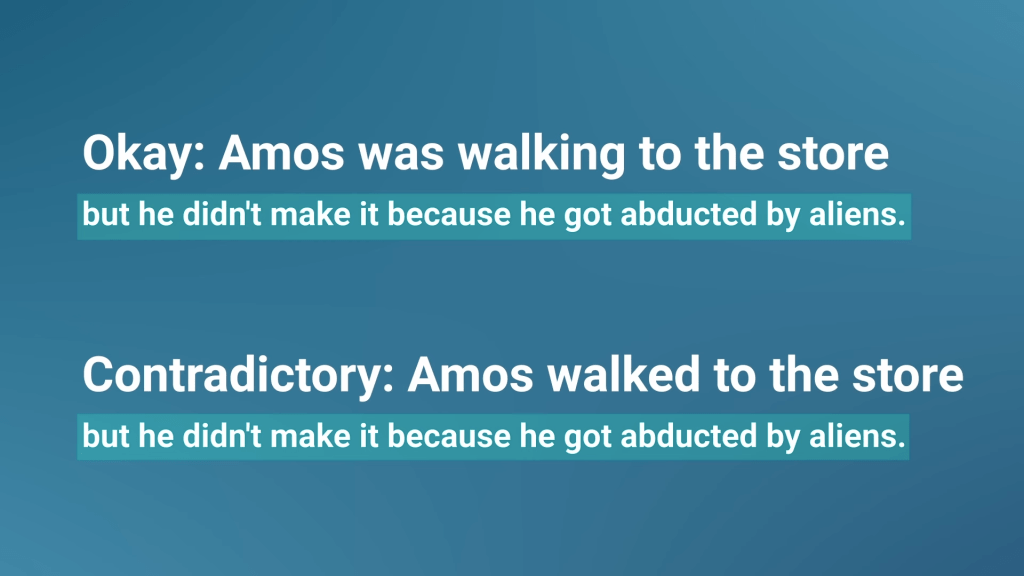

In the sentence ‘Amos is walking to the store’ the endpoint is when Amos reaches the store. However, this description with ‘Amos is walking’ does not tell us whether or not Amos actually reached the store.

He could have been abducted by aliens just before got there, so we cannot necessarily infer that Amos reached the store.In contrast, ‘Amos walked to the store’ does normally mean that Amos reached the store. It sounds contradictory to say ‘Amos walked to the store, but he didn’t make it because he got abducted by aliens on the way.’ When we say ‘Amos walked to the store,’ we infer that he got there. That is the perfective interpretation.

Many working on aspectual theory define imperfective not as disallowing a maximal stage but as not necessarily containing a maximal stage of an event. In contrast, the perfective would require a maximal stage. In other words, the imperfective allows for readings where the end of an event is reached, but the perfective aorist would require that interpretation. In fact, we do see overlap between the aspectual value of the present form and the aorist in the historical present. We will return to this in part 2 of the book where Campbell treats the historical present.

Coming back to Campbell, it is again difficult to know what would falsify his claim, but this also means that it cannot really be proven. Campbell uses the parable of the sower in Mark 4:14-20 to illustrate his theory. He concludes by saying that “Jesus explains the parable of the sower by laying out its meaning before the disciples’ eyes.” But this hasn’t been defined or demonstrated. It was asserted that this is what the imperfective is and that the present form is an imperfective. A passage is then given with present forms, and it is asserted that these fit the definition previously given. However, the example needs to demonstrate that the description given is actually true. Campbell seems to suggest that the imperfective is used because the explanation of the parable is an explanation, but of course, there are plenty of general statements made with the present tense form that are not offering a more detailed explanation of something else. In John 3:8, we have τὸ πνεῦμα ὅπου θέλει πνεῖ ‘the spirit blows where it wishes’. This is a very general statement, and in fact, the present tense form is often used for generics. It is also unclear how this could serve as a more detailed explanation for something previously said.

The temporal explanation for the parable is that an inspecific person is being referred to, so each of the presents should be read as a general statement or a habitual. These are statements that occur regularly. When you have many occurrences of an event in the time that you are discussing, it makes sense to use an imperfective form, which is generally more protracted over time than perfectives. Once again, there are much more detailed explanations of the relationship between imperfective and the habitual, and you can check out this article by Edit Doron and Nora Boneh (my former teachers) if you want to learn more about it.

After the aspect of the present, Campbell discusses how it relates to the imperfect form. Because he does not accept tense as part of the Greek verbal system, he has to distinguish between the present and imperfect forms, which both have the same aspect. He again appeals to spatial notions to distinguish between the two forms. Since he has already defined aspect as spatial, he has now suggested two spatial parameters for the present tense form: it is imperfective in aspect (which he describes as a detailed viewpoint) as well as proximate. He does not present any examples under the section of proximity from pages 41-43. I will treat this concept when we come to his excursus on space and time. The last example he does discuss in his treatment of the present illustrates the historical present. He rightly notes that most of the examples of the historical present are limited to certain verb classes, which he calls verbs of propulsion and verbs that introduce discourse. Given that historical presents often do fall into verb classes, I also agree that this should be part of the explanation. Again, we will return to this use of the present when he returns to it in the second half of the book.

The last form Campbell treats in chapter 4 is the imperfect. Within narrative, he rightly says that “imperfect indicatives tend to provide supplemental information.” It is true that this is a tendency and that the imperfect form tends to “describe details, provide reasons and explanations, and elucidates motivations.” It would seem that these functions are why Campbell calls the imperfect form an imperfective, which he describes as being a more detailed view of the situation. However, this is only a tendency and is not part of the meaning of the form. It is hard to see how a sentence like we have in John 3:1 provides a reason, explanation, or motivation. It says, Ἦν δὲ ἄνθρωπος ἐκ τῶν Φαρισαίων, Νικόδημος ὄνομα αὐτῷ, ἄρχων τῶν Ἰουδαίων ‘there was a man from the Pharisees, Nicodemus was his name, who was a ruler of the Jews.’ Here, the imperfect verb ἦν introduces a character in the story. This cannot be providing extra details about Nicodemus because he is only introduced here. This does not seem to fit Campbell’s definition of the imperfect as being a detailed (that is, imperfective) remote form (that is, one used in narrative).

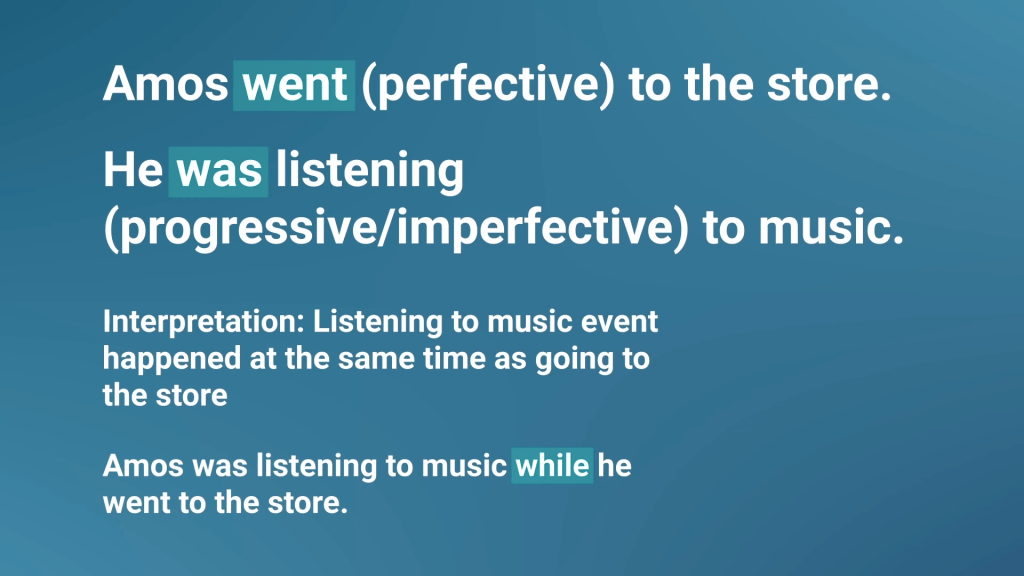

Again, the temporal explanation gives a reason why the imperfect would have a tendency to be used for background information in a narrative. Since perfective forms include the endpoint of an event, they move the narrative along. One event happens and ends, and then another event happens and ends, and so on. Since imperfective forms need not refer to the end of the event, they can refer to events that are happening simultaneously with another perfective form. For example, in a simple discourse like “Amos went to the store. He was listening to music,” we interpret the event of Amos listening to music as happening at the same time as the event of Amos going to the store. Since “Amos went to the store” normally includes the endpoint, and “Amos was listening to music” does not, we interpret the listening to music event as being part of the going to the store event.

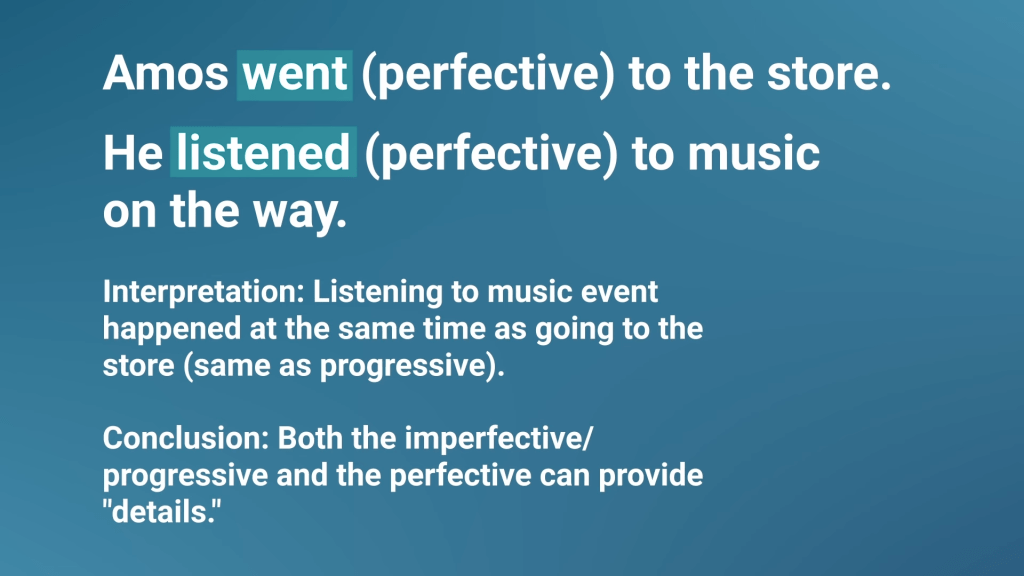

In this sense, it provides more details, but that does not make the progressive form encode a more detailed event. It just happens to be used that way in narratives because of how the two events are related temporally. In fact, we don’t need the progressive to provide more details. We can just as easily say “Amos went to the store. He listened to music on the way.” In this case, the simple p ast form (equivalent to the perfective) is providing the extra details. Because we specified that the listening took place “on the way” we understand that the events of going to the store and listening to music happened at the same time.

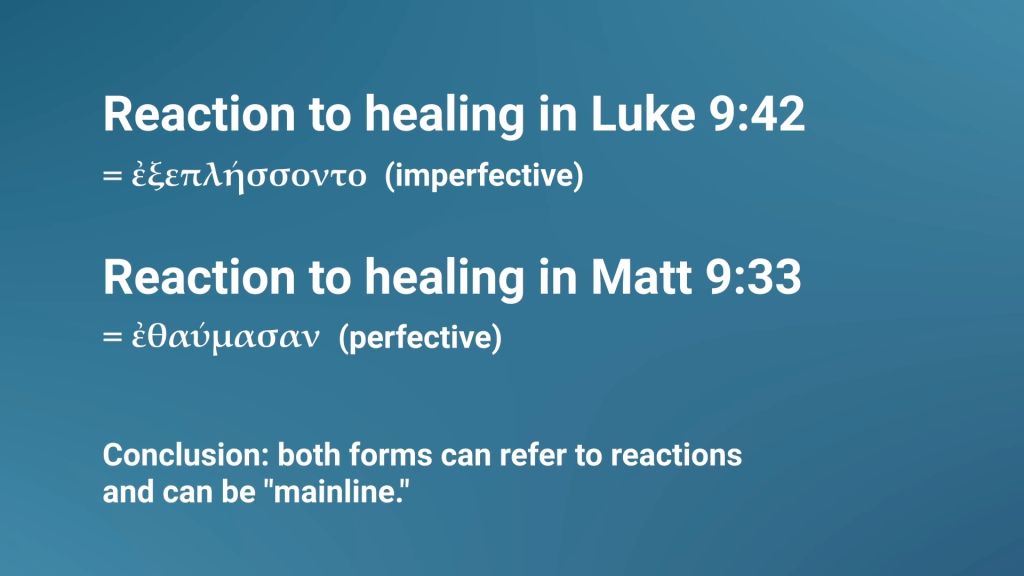

In Campbell’s example of Luke 9:42-45, not all imperfect verbs provide merely supplementary material. For example, the clause ἐξεπλήσσοντο δὲ πάντες ‘all were astonished’ refers to a response of the people within the narrative. After Jesus heals a boy and gives him back to his father, the people become astonished. The astonishment must happen after the healing, so this is an event on the mainline “sequence of events.” And in fact, we saw the similar word ἐθαύμασαν in the aorist in Matthew 9:33 where it was also a mainline event. In Luke 9:42, the reaction of all the people to a healing is described with ἐξεπλήσσοντο in the imperfect, but in Matthew 9:33, the reaction of the crowds to a healing is described with the aorist ἐθαύμασαν.

If Campbell says that the imperfect ἐξεπλήσσοντο is used in Luke 9:42 because it is a reaction, than we should also expect the reaction of ἐθαύμασαν to be in the imperfect, but it is an aorist. Our theory of the imperfective predicts overlap with the perfective, and this is where we see it. The verb ἐξεπλήσσοντο is what linguists would call an achievement predicate. This means that it has a natural endpoint but no duration. With these kinds of verbs, the imperfective is predicted to overlap with the perfective, since the endpoint of the event is the only part of the event. If it takes place at all, it ends. Both the imperfective and perfective would then refer to the end of the event with these kinds of verbs, which is exactly what we see here in this mainline imperfect form verb.

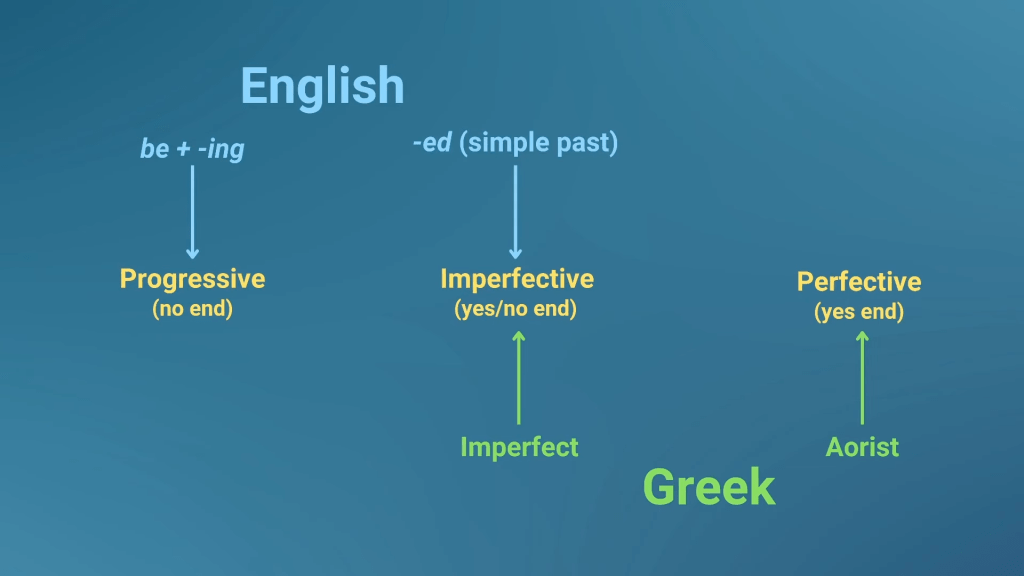

At this point, I want to briefly contrast the English and Greek verbal systems in order to show how they are different. This really has very little to do with Campbell’s work in that it is not directly engaging with his claims, but it will help clarify how linguists view the different aspects we have discussed, and hopefully, it will help when mapping English onto Greek and vice-versa. In English, there are two verb forms, namely what is called a simple past form, as in “Amos walked”, and a progressive form, as in “Amos was walking.” We have said that the progressive form disallows reference to the final stage of an event. Thus, a sentence like “Amos was walking to the store” cannot refer to the part of the event where Amos actually reached the store. The simple past tense form, however, can refer to the end of the event, so we most naturally interpret “Amos walked to the store” as meaning that he arrived at the store. However, as has been pointed out in the literature, English’s simple past form can also be interpreted to refer to only part of the event, similar to the progressive. With an example like “Amos read the Bible during church” we do not refer to the end of the Bible reading event. We are not to understand this to mean that Amos finished the entire Bible, which would be the natural endpoint of such an event. Rather, it means that he only read part of the Bible, and this is basically an identical interpretation to the progressive counterpart “Amos was reading the bible during church.” Thus, English’s system contrasts between a form that cannot refer to the end of an event (the progressive) and another form that may, but need not, refer to the end of the event (the simple past).

In contrast to this, Greek’s system morphologically marks the perfective meaning rather than the progressive. In other words, the contrast in its two forms is between one that necessarily includes a temporal boundary and one that may include a temporal boundary. This is why we see an overlap between the imperfect form and the aorist in our example comparing Luke 9:42 and Matthew 9:33. The imperfect form may still reference the end of an event. It just need not. However, because it is the only form that need not, it will often get the opposite interpretation to the perfective form, just like the English progressive and the English simple past will often have the opposite interpretation. Thus, the English progressive cannot refer to a temporal boundary, and the Greek aorist necessarily refers to a temporal boundary, and both languages have forms in the middle (namely the English simple past and the Greek imperfect) that may or may not refer to a temporal boundary. Because of how the different system s mark temporal boundaries, there will not be a one-to-one relationship between any of the forms. The imperfective forms in Greek, namely the present and the imperfect, may map onto either the progressive or the simple past/present tenses. In contrast, the perfective form in Greek may map onto the simple past tense, but the prediction is that it will not map onto the English progressive form.

Given how the two systems are set up, that is the only relationship that is disallowed. Hopefully, this helps you if you are trying to figure out how to translate between English and Greek.

I know we are in the weeds of the analysis, but the details matter. The Greek imperfective forms are often equated with the English progressive, but this is not how the two systems map onto each other, and linguists today do not equate progressive and imperfective forms. These kinds of details affect our translations, and they make or break our theories.