Introduction and Review

In this second part of my review of Campbell’s book “Basics of Verbal Aspect,” I will review chapter 2. Before we get into the review, however, there are three issues I want to address. First, my original post received a variety of responses, some positive and some negative. Campbell himself posted his own thoughts, and if I may try to summarize it, I would say that he felt personally attacked. Let me repeat what I said in the first video: I am not trying to bash Campbell. I am trying to help students, and so is Campbell. I applaud him for that. He wrote a book about aspect in Greek that was aimed at students and scholars who are not in the field of linguistics. My aim is the same. The reason why I am not writing a review of his book and sending it to some journal where it will be read by a handful of people is because I don’t believe that is the most effective way to teach students. These videos will get way more engagement from students (and even scholars) than a review in a journal, and that is what I am after. I am attempting to do this in a format that is engaging and helpful for students. As an aside, Zondervan was also giving out free copies of the book to anyone within the Nerdy Biblical Language Majors group in exchange for an honest review. I purchased the book myself, but I took this offer to be a sign that Zondervan wanted honest, fair reviews. Although I disagree with Campbell, I am trying to be both honest and fair.

So that is further justification for reviewing this book in particular (and Campbell’s PhD dissertation on the subject, for example) and doing so in this format. The second related point is that I want to personally encourage everyone to be cordial and respectful in their comments. I have refilmed this video in part to attempt to be as respectful as possible and to encourage others to do the same. Here, I would like to quote Campbell at the end of chapter 2: “It would help to take the heat out of debates around Greek verbs. It’s weird that tense-forms of an ancient language should generate so much passion and, at times, acrimony. Greek scholars are all trying to achieve more or less the same thing: to arrive at a more accurate understanding of how Greek verbs contribute meaning to ancient texts (including the Bible). Other disciplines within biblical studies manage to work through their differences without denouncing, mocking, or discrediting their opponents. Why can’t Greek scholars?”

Again, I applaud him for this and agree with him. I want to encourage all who listen to this to engage with the substance of what is being said on both sides and come to your own conclusions. If you do come to a conclusion, either for or against Campbell, I encourage you to express that conclusion with humility and respect if you wish to express it at all. Campbell has worked for a long time on this project, and it is not easy to have someone critique something you have worked hard on. Please acknowledge and respect that. To attack the person behind the opinion is not just unhelpful–it is not Christ-like, which is what we should all be striving for.

This brings me to my last point, which is more substantive and has to do with terminology. I tried very hard not to denounce or mock Campbell in my review of chapter 1, but I can imagine how one could think I was trying to discredit him, particularly with the question of how to understand terms. I said that Campbell used the terms aspect and aktionsart wrongly. In some ways, how you use technical terms does not really matter, but in other ways, it does. Let me explain. I began by saying that Campbell had the wrong definition of aspect and that he wrongly drew a distinction between “viewpoint aspect” and temporal notions of aspect. The term viewpoint aspect comes from Carlotta Smith, and she explicitly defines it as temporal. My claim was stronger. Linguists working on aspect universally describe it as temporal. Here are some examples from introductory semantics textbooks or reference works:

Nick Riemer says that aspect is “about whether time is seen as moving through the event” or “about time in the event.” (Introducing Semantics, pg. 314)

Paul Kroeger says “aspect indicates a temporal relation between the Topic Time and Time of Situation.” (Analyzing Meaning, pg. 385)

Susan Rothstein says “aspectual properties of a verbal predicate reflect the internal temporal make-up of the situations or events denoted by the predicate” (Cambridge Handbook of Formal Semantics, pg. 342)

In addition to being found in all kinds of linguistics works (and if there are any counterexamples that I don’t know of, feel free to comment about them), this definition is also standard in more open source platforms, such as Wikipedia, which says, “In linguistics, aspect is a grammatical category that expresses how a verbal action, event, or state, extends over time.” ChatGPT says something similar: “Grammatical aspect is a linguistic feature that conveys the nature of an action or state in terms of its temporal structure and progress. It helps to express how an event or action unfolds over time.”

Finally, the World Atlas of Language Structures is an online database that can be found at wals.info. It is a database of hundreds of languages where they are each categorized by certain features. In their introduction to tense and aspect, they state the following: “Among the multitudinous definitions of tense and aspect in the literature, we may cite those given in Comrie (1985: 6): tense is grammaticalisation of location in time, and aspect is “grammaticalisation of expression of internal temporal constituency” (of events, processes etc.). Thus defined, the two categories are conceptually close in that both deal with time.” This might sound like there is not agreement in the field of linguistics on the definition of aspect, but everyone they cite, though having slightly different definitions of aspect, agree that it is temporal. The of the field (which I often hear from biblical scholars but not linguists) is not whether aspect is temporal, but it is how precisely to define aspect temporally.

I belabor this point because when I said Campbell is wrong about his definition of aspect, what I meant was that the field of linguistics uses it in a different way, as shown by all the examples. If the way Campbell used the term “aspect” applied only to Greek grammatical studies, we would then have to evaluate how those scholars are using the term. However, Campbell does not claim that his definition of aspect only applies to Greek. While acknowledging the temporal view, he also suggests that his definition is general and can apply to English, even stating that “Most, if not all, languages have ways of expressing these two different viewpoints.” His example on page 10 for English is: “I walked down the street” vs. “I was walking down the street.” Campbell says that the difference between these two sentences is “verbal aspect”. Here’s where terminology matters. Everyone agrees that the difference between “walked” and “was walking” is aspect. However, Campbell defines aspect differently than all the linguists who wrote the introductory textbooks, the open source definitions of aspect, and the World Atlas of Language Structures that is categorizing hundreds and hundreds of languages. All the linguists I have cited are defining it temporally. Campbell explicitly claims that it is not temporal, and he presents his claim as if Comrie is a revolutionary within the linguistics world and is not followed by the entire field. In this instance, terminology matters. Either the distinction between “walked” and “was walking” is temporal, or it is not. Linguists have argued that the distinction is temporal. They call that distinction aspect. Campbell has argued that the distinction is not fundamentally temporal. He also calls it aspect. When I say that Campell has the wrong definition of aspect, I mean that he does not use the accepted definition in the field that has come up with that technical term.

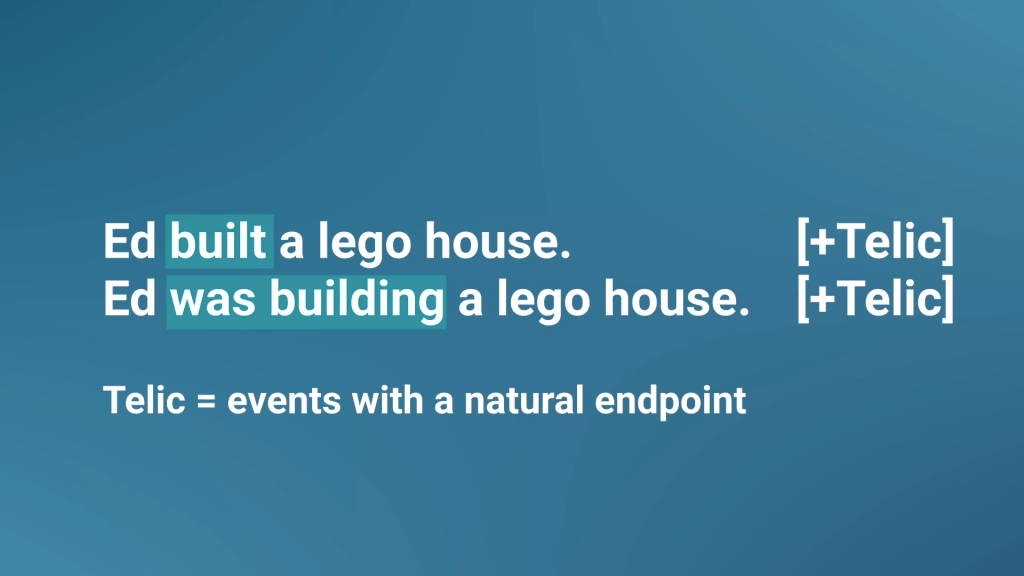

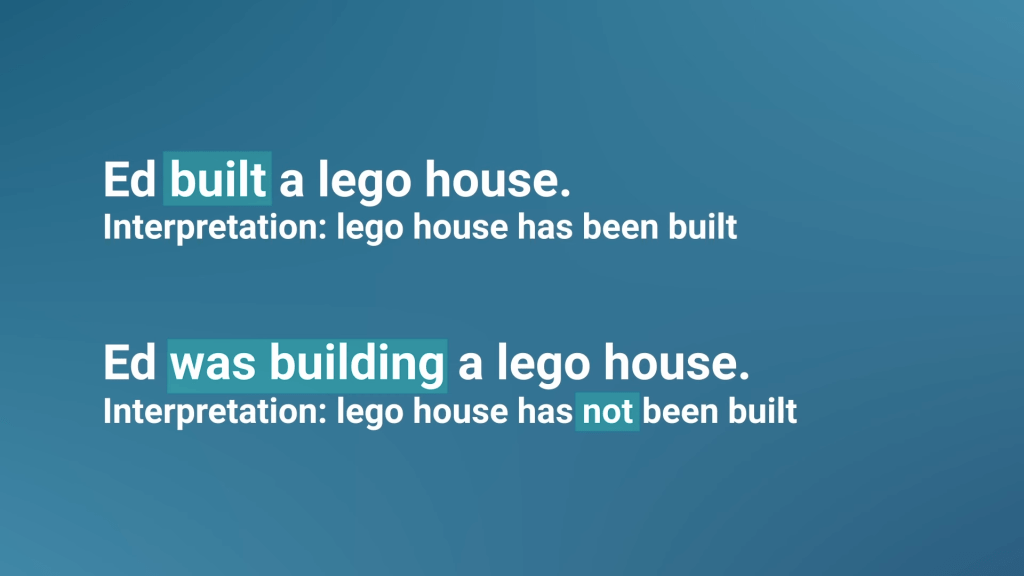

In other instances, terminology is less consequential. For example, I am not going to provide all the examples for the term aktionsart, but I could do the exact same thing. It is universally regarded as the temporal structure of the event and not the interpretation of a verbal description in context. Both “Ed built a lego house” and “Ed was building a lego house” have the same aktionsart value even though they have different interpretations. Both refer to a “building a lego house” event which has a natural endpoint, namely when the lego house is completely built.

They have different interpretations in that “Ed built a lego house” references the endpoint (I infer that the lego house has been built), but “Ed was building a lego house” does not reference the endpoint (I cannot infer that the lego house has been completely built).

Campbell uses the term aktionsart to refer to the interpretation of the sentences rather than the contribution by the verbal description (namely that the event has a natural endpoint or not). This is not how linguists use the term aktionsart today, but this does not matter very much other than that it can be confusing to people who read about aktionsart on Wikipedia or in semantics textbooks. As much as possible, I will point out these differences to help you understand this confusing world, but I will not evaluate Campbell’s actual analysis based on my definitions. He needs to be read using his own terms. What he calls aktionsart, I would call the interpretation of a verbal form or one of its uses. In this case, the terminological distinction is not as consequential.

Chapter 2 Analysis

As we will see, our differences are not just about terminology. The issue is that the categories and terminologies change the way we analyze the text. Let’s now get into chapter 2, which covers some of the history of the field, particularly within Greek grammatical studies, and it focuses especially on the last 50 years or so. In Campbell’s survey of scholars who have worked on Greek aspect, the only linguist proper cited is Mari Broman Olsen who did her PhD in linguistics at Northwestern University and wrote on aspect in English and Koine Greek.

Campbell cites her as defining aspect “differently,” namely as temporal. He says that she follows Comrie in this respect, but as we have said, this is everyone within linguistics. Other formal semantics scholars who have worked on aspect in Classical and New Testament Greek are not cited. For example, Gero and Von Stechow’s work on the diachrony of the Greek perfect, in which they discuss the New Testament, is not mentioned. Likewise, Corien Bary’s dissertation, Aspect in Ancient Greek, is also not cited. Though one could argue this is because she is dealing with Classical Greek rather than Postclassical or New Testament Greek, her analyses remain valuable and useful for all students of New Testament Greek. In a later video, I will return to Campbell’s review of The Greek Verb Revisited.

Campbell cites her as defining aspect “differently,” namely as temporal. He says that she follows Comrie in this respect, but as we have said, this is everyone within linguistics. Other formal semantics scholars who have worked on aspect in Classical and New Testament Greek are not cited. For example, Gero and Von Stechow’s work on the diachrony of the Greek perfect, in which they discuss the New Testament, is not mentioned. Likewise, Corien Bary’s dissertation, Aspect in Ancient Greek, is also not cited. Though one could argue this is because she is dealing with Classical Greek rather than Postclassical or New Testament Greek, her analyses remain valuable and useful for all students of New Testament Greek. In a later video, I will return to Campbell’s review of The Greek Verb Revisited.

Instead of going through the other scholars one-by-one, it is probably more helpful to go over the main “area of agreement” in the field. Campbell’s first point is that “Aspect is defined as viewpoint, which is a spatial rather than temporal concept.” We have already cited copious works from linguistics to show that this is not how linguists define the term. The fact that this is an area of agreement within studies on aspect in the New Testament shows that the authors surveyed disagree with the field of linguistics. This does not tell us who is correct, but we would then have to conclude that the scholars who have spent their entire lives categorizing hundreds of languages based on a temporal aspectual distinction are wrong. We would also have to conclude that aspectologists (no, I did not make that term up–these are the linguists specializing in aspect), such as Susan Rothstein, Daniel Altshuler, and Hana Filip are also wrong. They all agree that aspect is temporal and have spent much of their careers trying to figure out what aspect is. But most importantly, I will show that the temporal definition of aspect explains the data.

Campbell’s next section is an excursus on tense. So, what is tense exactly? Campbell defines it as “the ways in which verbs indicate time–specifically the time at which verbal actions take place,” and he clarifies that “tense always indicates time in re lation to something else–usually the time of speaking or writing” (pg. 28). From these statements, Campbell’s definition of tense can be summarized as the relationship between the time of the situation or eventuality and another time, usually the time of speaking. The terms situation or eventuality are used in linguistics as cover terms for events or states that verbs refer to–this is what Campbell calls the “verbal action,” but because not all verbs refer to actions, I will use the term situation or eventuality as linguists do. So is tense the relationship between the eventuality and the time of speaking?

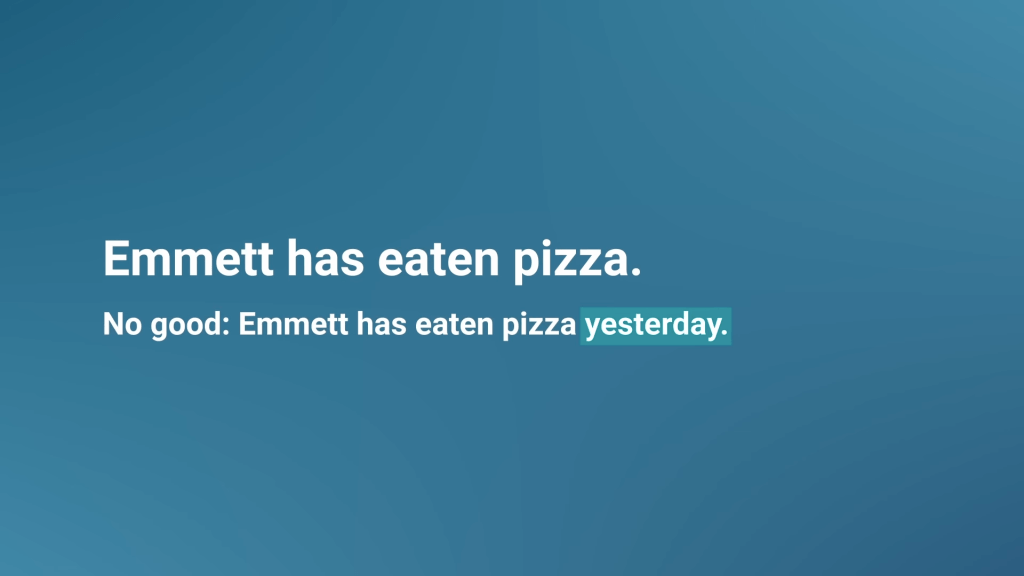

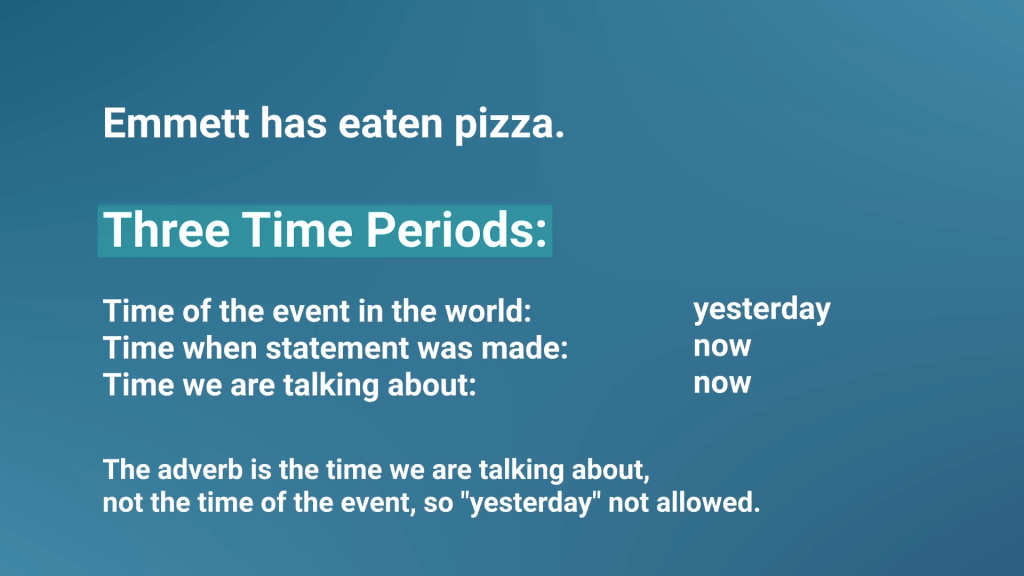

It is not. Sentences like ‘Emmett has eaten pizza’ show that this is not the case. The tense in this sentence must be in the present, since we cannot combine this with past-referring adverbs. You cannot say *’Emmett has eaten pizza yesterday’.

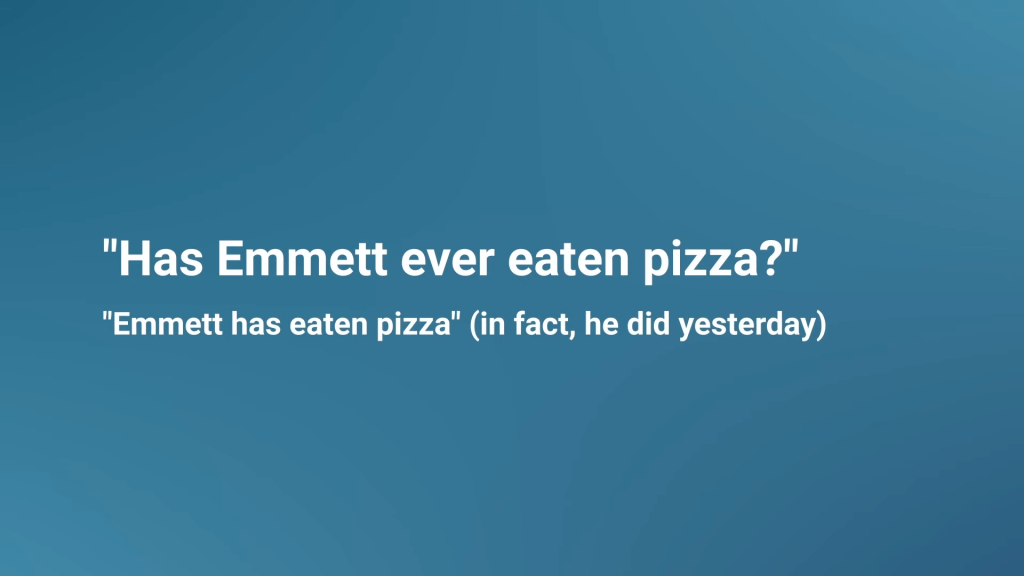

However, if I am asked the question ‘Has Emmett ever eaten pizza’, I can answer ‘Emmett has eaten pizza’ even when the event took place yesterday. This means that the time we are referring to with an adverb like yesterday is not necessarily the same as when the event took place. Essentially, this means that we have three time periods in such an example. We have the time when the event took place in the world. That was yesterday. And then we have the time when the statement was made, the speech time. That’s the present.

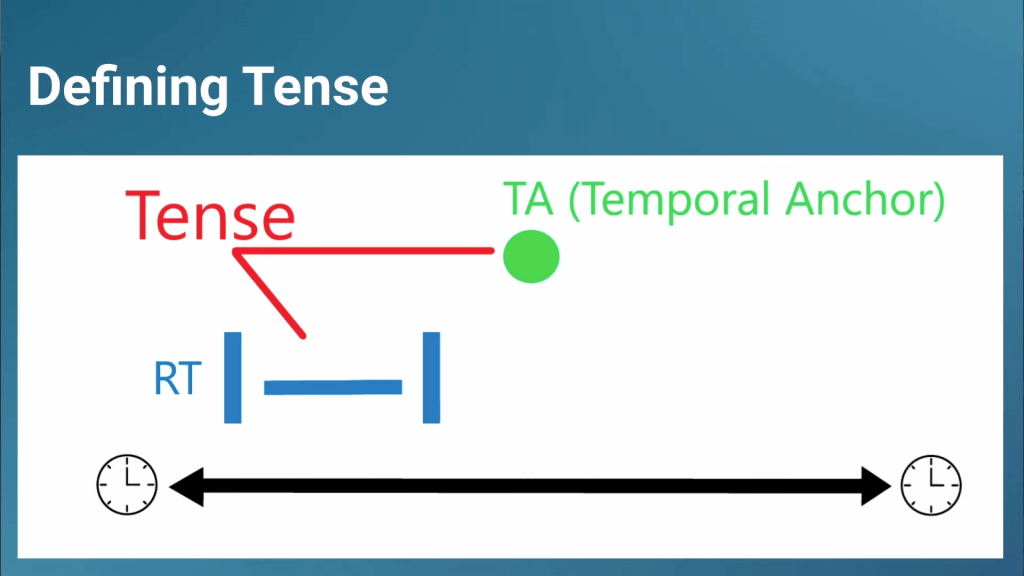

We also have a third time, the time we are talking about, which linguists call the reference time or topic time. In the case of ‘Emmett has eaten pizza’, the reference time is the present, since we cannot use past adverbs, but the time of the eventuality is the past, since Emmett actually did eat pizza yesterday. In other words, the perfect have form in English necessarily refers to the present even when a past situation has occurred. This gives us the tools to define tense: it is the relationship between the time of speaking and the reference time and not the relationship between the time of speaking and the time of the eventuality.

Even the speech time, however, has its own complexities. It would be perfectly natural for me to start a story about Ancient Rome with “The year is 44 BC. Julius Caesar has just been killed.” Despite the fact that the year is not 44 BC and Julius Caesar was not just killed, we can use the present tense to talk about a year that occurred before our present moment. The narrator can place himself at any time period in a story, and tense is then related to that time period rather than the narrator’s real time of writing or speaking. This shows that tense is actually not the relationship between the reference time and the time of speaking, but between the reference time and some temporal anchor, which is only sometimes the time of speaking. The so-called historical present is not an argument against the present form being a present tense, either in English or in Greek. It is an illustration of how the temporal anchor may change in stories.

Coming back to Campbell’s discussion of tense, he says that the aorist indicative refers to the past 85% of the time, and the present form refers to present time only 70% of the time, but if he is relating the time of speaking to the time of the event, then these statistics mean nothing. Linguists wouldn’t call that present or past tense. Instead of explaining the data by looking more closely at the definition of tense, Campbell essentially claims that the issue is about whether you hold to the distinction between semantics and pragmatics. I hold to this distinction (again, see video 1 and my two videos on the basics of semantics and pragmatics), but that is not the real issue here. The real issue is the theoretical definition of tense to begin with, which led to the data being tallied in the way that it has been. The present tense form refers to present tense 70% of the time under Campbell’s definition of tense, but not under my definition of tense, which is how linguists would define it. Again, we will soon see how this affects our explanation of the data.