What is TAM (Tense, Aspect, and Modality)?

TENSE and ASPECT are about how situations (events and states) are placed in time, and MODALITY concerns whether something is possible or necessary. These are SEMANTIC categories rather than MORPHOLOGICAL. By semantic categories, we mean that they have to do with the meaning of the sentence rather than morphological which has to do with linguistic forms. For example, we can talk about the -ed suffix in English as a certain form (morphology) with a particular meaning (semantics). These two categories often only partially overlap in languages: something like the –ed suffix may map onto the semantic category of tense only incompletely. In this vein, we must distinguish between the meaning contribution of a particular form (or MORPHEME) in a given language and the notional semantic categories that allow us to describe the potential interpretations of that form.

Tense

Tense is a relationship between the interval of time being talked about and the time of speaking. A crucial notion here is the REFERENCE TIME (RT), which is the interval of time being talked about. The RT can be before, during, or after the SPEECH TIME (ST), and these correspond to past, present, and future. Past tense, then, means that there is an interval of time we are talking about (RT) that precedes the time of speaking (ST).

(Alternate labels for Speech Time, Reference Time, and Event Time (discussed below) are given by Klein 1994 as the Time of Utterance (TU), Topic Time (TT), and Time of Situation (TSit). You will find both in the literature, and Biblingo users will recognize the latter terms, but they essentially amount to the same thing.)

Let’s take an example like Did John turn off the light? This question is not asking whether there was any point in the past that John turned off the light. It is asking whether John turned off the light at a specific time in the past, whatever time we might happen to be discussing (or referring to) in the context. So tense is a relationship between the speech time and the time we are discussing, i.e. the RT.

The implication of this is that tense is not a relationship between the ST and the EVENT TIME (ET). Let’s go back to our example to see what would happen if this were the case. This would mean that Did John turn off the light? would be interpreted as something like Did John turn off the light at any point prior to now? but that is clearly not what is being asked. Rather, the question assumes there is a specific time (the RT) prior to the ST that we are discussing. If we are talking about what happened this past Tuesday before John left the house, we cannot respond with Yes, he turned off the light in 1974, though if tense were a simple relationship between the ST and the ET, we actually could truthfully respond with such an answer. This would be the case since all we would need would be one instance of John turning off the light (the ET) prior to the ST rather than how we actually understand the sentence as whether that event took place within a specific RT we are discussing, in this case last Tuesday. Here are the temporal relationships of each of the tenses:

Aspect (or Grammatical Aspect)

So we have established that tense is a relationship between the ST and the RT, but what is aspect? Aspect has to do with how the event relates to the time we are discussing. In other words, it is the relationship between the RT and the ET. This is often described as how the speaker chooses to portray the event, since he or she may choose to discuss only part of the event or the entire event, for example. There are three main aspects often discussed: PERFECTIVE, IMPERFECTIVE, and PERFECT.

Perfective

Perfective aspect is when the speaker is referring to the entire event. Since we have already established that the speaker is normally referring to a specific interval of time (called the RT), this means that the time of the event has to be entirely included in the RT. In other words, both the beginning and end of the event are included within the time being discussed. An example of this is something like John ate dinner, which normally means that John both started and ended his dinner in the time we are discussing. So in a sequence of statements like John finished work. He ate dinner. He left. we normally interpret each of the events happening in succession because we present each whole event right after another. We can represent this aspect with the following diagram:

Imperfective

Imperfective aspect is when the speaker is referring to part of the event. In English, this is normally done with the be + -ing form as in John was eating dinner. In this case, the verb form is used by the speaker as a way of including the RT within the ET. Because the ET extends beyond the RT, only part of the actual event of eating is being referred to. So, the speaker might be discussing what happened between 5:15-5:30 where he or she might say John was eating dinner, but this way of describing the event suggests that John started before 5:15 and ended after 5:30. He might have actually eaten between 5:10-5:40, for example. Thus, the speaker is only discussing part of John’s mealtime. This can be represented by the following diagram:

Perfect

Perfect aspect is usually described as a prior situation with some kind of current relevance. Just like perfective and imperfective aspect, it can be described in temporal terms. Since the relevance of the event comes after the time of the event, the perfect simply means that the RT follows the ET. In English, we use the have + -en form for this as in John has eaten. This means that the prior event of John eating is relevant in some way to the current discussion, since the RT is in the present. Our diagram for the perfect is the following:

Aktionsart (or Lexical Aspect)

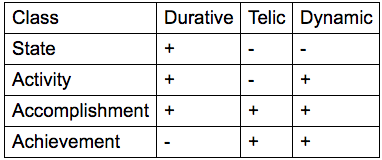

Grammatical aspect must be distinguished from what is called AKTIONSART/LEXICAL ASPECT. Whereas grammatical aspect has to do with how temporal relations are construed in the grammar (usually through things like suffixes), aktionsart involves temporal and qualitative characteristics of events themselves that verbs refer to. In other words, the category of aktionsart is a closer look at the ET, such as the kind of event or its temporal boundaries. The philosopher Zeno Vendler (1957) gave the four basic aktionsart categories that were distinguished on the basis of three traits, as shown in the following chart:

Dynamic

Beginning from the right side, DYNAMIC is about whether the SITUATION or EVENTUALITY has some sort of movement or change (linguists often use the term situation or eventuality as a cover term for both events and states). If the situation is dynamic, any two given intervals of that situation are not necessarily the same. So a situation like run (an activity) varies as it progresses, but something like know French (a state) does not vary.

Telic

TELIC situations are those that have natural endpoints. For example, run does not have a natural endpoint, but build a house (an accomplishment) does, i.e. when the house has been constructed. This distinguishes the atelic class (states and activities) from the telic class (accomplishment and achievement).

Durative

DURATIVITY has to do with whether the situation is extended in time or not. Accomplishments like build a house differ from achievements like break a vase in that the former take time to reach the endpoint, but the latter are not protracted in time.

An important point to note is that the classes are not necessarily classes of verbs but a combination of verbs and their ARGUMENTS (what is needed to complete the thought of the situation named by the verb). A situation like John ran is atelic, since there is no natural endpoint that is expressed. However, a situation like John ran to the store is telic, since we have expressed an endpoint, namely John’s arrival at the store. Likewise, a sentence like Mary built the house is telic, since there is a natural endpoint, but Mary built houses is atelic, since this sentence does not express a natural end of Mary building houses (she could have built 3, 4, 5, or 200 houses – we don’t know). Aktionsart, then, is not just about verbs, but about verbs and the arguments.

Aktionsart classes interact with grammatical aspect in special ways. The English progressive normally requires the predicate to be both durative and dynamic. This makes both states and achievements to be normally disallowed by the progressive (or at least, they get a special interpretation). A sentence like Mary knows French is very odd in the progressive: #Mary is knowing French (I use the # symbol for a sentence that is semantically ill-formed). Likewise, John turned off the light is an achievement, since the event of him turning off the light does not have any duration. This is also often odd in the progressive, such as in ?John was turning off the light. An achievement with the progressive often requires us to stretch out the event of John turning off the light, normally to include the time just before John turning off the light to accommodate for the fact that the progressive does not combine easily with situations not protracted in time.

Modality and Mood

Modality

MODALITY deals with what is possible or necessary and not the “here and now”. It is a semantic category that is not unique to verbs. Adjectives like imaginary, for example, are also modal since it deals with something that is possible. Auxiliary verbs like might and must are modal as well, the former encoding that something is possible and the latter that something is necessary (e.g. compare John might be washing the dishes to John must be washing the dishes). The category of modality is used to analyze things like habituals, future, the subjunctive, etc. within verbal systems.

Mood

MOOD is used in a variety of different ways in the literature, but the most pertinent for the semantics of verbs is what Paul Portner terms VERBAL MOOD. Within languages, this category refers to moods like the subjunctive, imperative, and optative. Portner’s definition (2011) is the following: “Verbal mood is a distinction in form among clauses based on the presence, absence, or type of modality in the grammatical context in which they occur.” According to this definition, the “subjunctive” would be a different form that marks the presence, absence, or type of modality in the grammatical context. Thus, verbal mood is the grammatical marking of some modal element (for other ways that the term ‘mood’ is used, see (Portner 2011; 2018).